| Applications | |

Geospatial techniques for modelling the environmental niche of the species

Geospatial tools helped confirm Indian Giant Squirrel presence in the Kanha Tiger Reserve |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A protected area network like Kanha Tiger Reserve, in general, protects and manages a vast spectrum of wildlife. However, the conservation of charismatic large mammals and wildlife of high conservation value tends to overshadow all other wild animals and birds. The perceived ordinariness of these wildlife species in protected areas have also become one of the main causes of their not receiving due attention for detailed systematic studies therein, and rapid decline outside in managed forests. The fauna of Kanha Tiger Reserve (KTR) supports the endangered tiger (Panthera tigris tigris) and vulnerable hard ground barasingha (Cervus duvauceli branderi) and a wide range of larger mammal species and birds. The fauna also includes an amazing arboreal mammal species – Indian giant squirrel (Ratufa indica Erxleben). The species belongs to the family Sciuridae of order Rodentia. The significance of the conservation of Indian giant squirrel in the tiger reserve lies in the endemicity of this mammal species to India and its consequent implications for conservation in managed forests still supporting small populations of this species.

An endemic species to India, it commands a wide distribution in Peninsular India, from evergreen forests to moist and dry deciduous forests of eastern and western ghats to central India (Baskaran et al. 2011). The Indian Giant squirrel has been categorised as of Least Concern with decreasing population trend in the Red List of IUCN (Rajamani et al. 2014). It has been placed under Schedule II in the Indian Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972 (as amended). Ghosh and Bhattacharyya, 1995 described the occurrence of this species in KTR. They, however, recorded only one animal near the Banjar River in the Mukki forest range. Some forest guards and visitors reported its sighting at a few sites in the Supkhar forest range.

Methodology

A systematic procedure was followed for this rapid study of its occurrence. Space Applications Centre, ISRO used the presence record of Mukki and Supkhar forest range sites and Pachmarhi area, along with occurrence records in Western Ghats using global biodiversity information facility (GBIF) repository for training eight different environmental niche models (Bioclim, climate pace model (CSM), environmental distance (ED), Envelope Score, genetic algorithm for rule set production (GARP), maximum entropy (MaxEnt), Niche Mosaic and support vector machine (SVM)). These environmental niche models are aimed at providing a detailed prediction of distribution by relating presence of species to environmental predictors (Araüjo and Williams 2000, Scotts and Drielsma 2003, Mac Nally and Fleishman 2004, Singh et al. 2013).

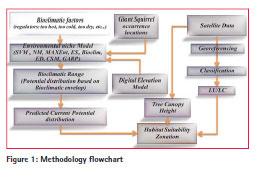

The landuse/ landcover (LU/LC), digital elevation model and tree canopy height were also incorporated with 19 spatial bioclimatic indices (representing hotness, coldness and wetness in the region), to identify potential niche of Giant squirrel with similar climatic and LU/LC preferences (Figure 1). The canopy height information was taken from ICESAT-GLAS LIDAR product as this is an arboreal animal that prefers to live on tall trees. The niche model results were combined in GIS domain, suitably weighted with LU/LC and tree canopy height data to minimize uncertainty and bias in the predictions.

Findings and Action

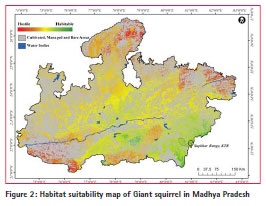

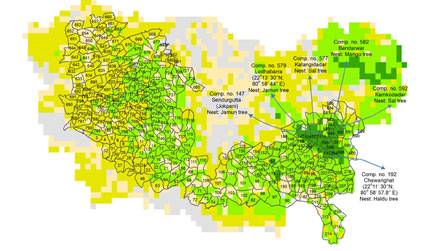

The model outputs suggest that the fundamental niche of this species could reach as far north as the Satpura hill range of Madhya Pradesh (approx. 22° N) and Dindori Range (approx. 23° N) in Madhya Pradesh. The result supported that parts of the Supkhar range has high habitat suitability for the species (Figure 2). Kanha Tiger Reserve and Space Applications Centre, ISRO, Ahmedabad in a joint campaign on May 20, 2013, recorded presence of three individuals of the Giant squirrel (one being in pair and other in solitary) and many dreys. The map showing Supkhar as one of the most suitable zone in KTR, was used for field verification and opportunistic sightings of the mammal (Figure 3) and ad libitum identification of trees within the most habitable zones were recorded. Close observations of the movements of this arboreal mammal for long hours revealed the presence of 20 dreys in several trees species. The GPS coordinates of each of the trees with dreys, along with its species, within one hectare were recorded. Total 50 tree species out of 900 species (Negi and Shukla 2010) in KTR were found in its habitat. Drey presence was recorded on Ficus racemosa, Shorea robusta, Syzygium cumini, Ougeinia oojenensis, Kydia calycina, Bauhinia retusa, Terminalia tomentosa, Mangifera indica, Adina cardifolia and Buchanania lanzan.

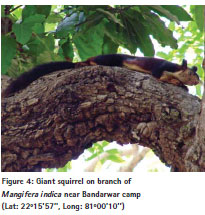

In this study, four forest beats were found supporting the nesting sites of the Indian giant squirrel in the Supkhar range. The mammal (Figure 4) was observed to feed on a wide range of plant parts, including fruits, flowers, seeds, young leaves and bark of Cassia fistula (Amaltas), Diospyros melanoxylon (Tendu), Emblica officinalis (Aonla), Ficus bengalensis (Bargad), Ficus racemosa (Umar), Grewia tiliaefolia (Dhamin), Mallotus philippensis (Sendur), Mitragyna parvifolra (Mundi), Ougeinia oojenensis (Tinsa), Schleichera oleosa (Kosum), Syzygium cumini (Jamun), Terminalia tomentosa (Saja), Terminalia chebula (Harra), Terminalia belerica (Bahera) and Ventilago denticulata (Keotibel).

Conclusion

The Supkhar forest range of KTR is one of the six forest ranges of the core zone or Critical Tiger Habitat. The forest range typically represents the floral and faunal attributes of the Kanha core zone, with sal (Shorea robusta) and miscellaneous forests. The climate of the study site is typical monsoonal, with average annual rainfall around 1,300 mm. Temperature soars to 45oC in summer and may drop to even -2oC for a few days in winter. This bio-climatically unique forest range of KTR showed the maximum value of the fundamental niche indicating potential climatic conditions for Giant squirrel. More such efforts will be required within this fundamental environmental niche to understand its current status and abundance in the area to save it from local extinction. The squirrel is mainly hunted for meat and trade therefore; its habitats need to be specially protected through regular monitoring of all nesting sites.

Acknowledgements

Authors are thankful to Dr A S Kiran Kumar, Chairman, ISRO and Director, SAC (ISRO) for the encouragement. The authors are also thankful to Shri Ajit Sonakia, PCCF (Working plan division), MPFD for his direct and indirect help during the course of the work. Thanks are also due to Shri O P Tiwari, Deputy Director, KTR, Shri P K Verma, Assistant Director, KTR, Shri Bhura Gaekwad, Range Officer, Supkhar, KTR and other field staff of KTR. The WorldClim data portal, OpenModeler developers, ICESAT-GLAS product and NRDB data repository is thankfully acknowledged. The study is part of EMEVS project under ISRO-GBP.

References

Araüjo, M. B. and Williams, P. H. 2000. Selecting areas for species persistence using occurrence data. Biological Conservation 96: 331-345.

Baskaran, N., Venkatesan, S., Mani, J., Srivastava, S.K., and Desai, A.A. 2011. Some aspects of the ecology of the Indian giant squirrel Ratufa indica (Erxleben, 1777) in the tropical forests of Mudumalai wildlife sanctuary, southern India and their conservation implications. JoTT Communication 3(7): 1899–1908.

Ghosh, R K and Bhattacharyya, T.P. 1995. Fauna of Kanha tiger reserve Madhya Pradesh, Fauna of conservation series-7. Zoological Survey of India, Calcutta.

Mac Nally, R. and Fleishman, E. 2004. A successful predictive model of species richness based on indicator species. Conservation Biology 18: 646-654.

Negi, H.S. and Shukla, R. 2010. Tiger conservation plan for the Kanha Tiger Reserve, sub-plan- core zone (for the period 2010-11 to 2020-21).

Rajamani, N., Molur, S. & Nameer, 2014, P.O. 2010. Ratufa indica. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2014.3. www.iucnredlist.org. Downloaded on 10 February 2015.

Scotts, D. and Drielsma, M. 2003. Developing landscape frameworks for regional conservation planning: an approach integrating fauna spatial distributions and ecological principles. Pacific Conservation Biology 8(4): 235-254.

Singh, C.P., Panigrahy, S., Parihar, J.S. and Dharaiya, N. 2013. Modeling environmental niche of Himalayan birch and remote sensing based vicarious validation. Tropical Ecology 54(3): 321-329.

(6 votes, average: 3.17 out of 5)

(6 votes, average: 3.17 out of 5)

Leave your response!