| Applications | |

UAVs: A boon for mapping applications

|

|

UAVs (Unmanned Aerial Vehicles), or as most civil aviation authorities now call them, UASs (for Unmanned Aircraft Systems), are attracting a lot of attention lately from geospatial professionals. Common questions in their minds are:

• What applications can I use it in?

• What benefits can it provide to my organization or my clients (or data users)?

• How do I implement such a system in my organization?

This article will cover the first two questions, while addressing some of the third question as well.

High-Level System

Unmanned aircraft are either a fixed-wing (plane) or a multi-rotor (helicopter) design. Typical fixed-wing UAS available today are equipped with wide-angle cameras that fly about 100 m (more or less) above the ground. Multi-rotors, with their ability to hover, move vertically—and even fly in reverse—may sometimes be operated at lower heights above ground. A greater diversity of sensors are being developed and offered specifically for small UAS platforms. Some of these include near-infrared cameras, miniaturized LiDAR scanners, and even sensors that enable hyper-spectral or multi-spectral capabilities. The typical system runs on electrical power and flights are between 30 and 60 min in length (often shorter for multi-rotors because of the greater amount of energy needed to achieve a mission). Depending on the endurance and speed of fixed-wing aircraft, typical coverage is around 1 to 1.5 sq km (100- 150 ha); for multi-rotors the area covered is much less—it could be as little as 10 percent to as much as 30 percent of what can be achieved with a fixed-wing UAS.

UAS image processing is usually done using close range photogrammetric

techniques adapted to exposures taken in flight. This technique allows accurate construction of photogrammetric models that approach the quality achievable with much more sophisticated manned aerial systems flying at much higher altitudes.

With these technologies, photomosaic, orthophotographs, digital terrain models (DTMs), digital surface models (DSMs) and point clouds can be output. Without ground control the models have high, cm level internal consistency in X, Y and Z. With sparser ground control than is typically required for conventional photogrammetry, good quality models registered to the ground control can be rapidly generated at much lower costs than most other methods of achieving similar results. That, however, doesn’t make today’s UASs a solution for all aerial surveying and mapping situations; but where their application is appropriate, they bring benefits that are sometimes unique.

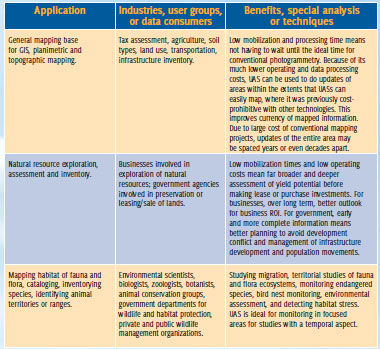

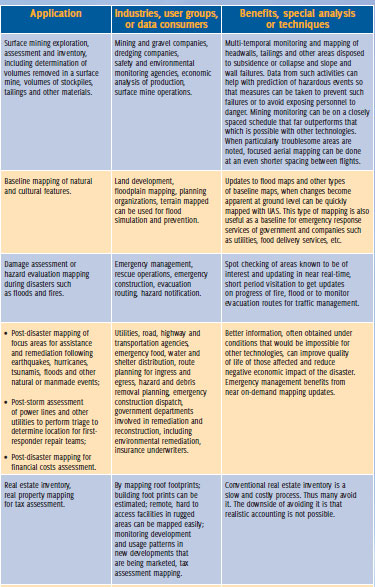

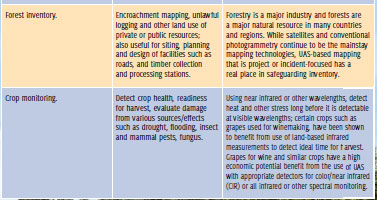

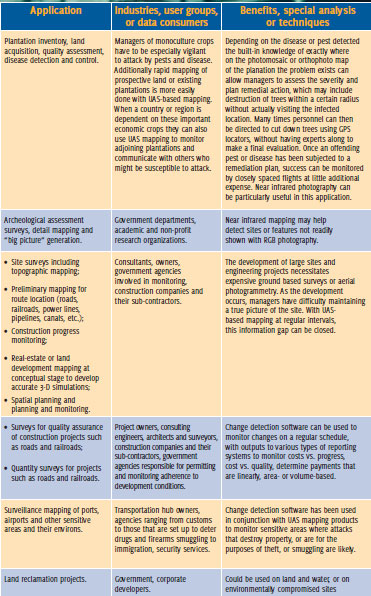

Some of the more common applications of UAS-based mapping are listed in the table, with a limited set of users and data consumers for each type and special benefits that may be unique to UAS aerial imaging.

UAS aerial imaging can provide flexibility unsurpassed by other technologies. Portable equipment that is able to function in a wider variety of adverse weather means that mapping can be done closer to the time of need. Because mobilization and flight cycles are short, flights can be done hourly or more frequently in urgent situations such as floodwater or fire tracking. Cloud cover is rarely a problem as unmanned aircraft typically fly below the clouds. In fact in some parts of the world it is being considered as the only mapping tool for aerial mapping as the weather, availability of aircraft, other equipment and trained personnel rarely coincide to allow opportunities for conventional aerial mapping. When focused areas need to be mapped with timely generation of data products under conditions—weather, hazard limitations, or closely spaced visitations—that test the capabilities of other tools, the selection and successful use of UAS in such situations is only limited by the solution-provider’s creativity.

Operational issues and working within a nation’s civil aviation regulatory framework must be examined in detail before an organization decides to acquire and fly UAS for geospatial applications. UAS flying is highly process-oriented. It involves much more planning and preparation than the typical use of ground-based technologies involves. Training of flight crews and data processing teams is more than just an up-front investment. It is necessary for flight crews to maintain current skill levels through non-revenue flights if the revenue flight schedule is widely spaced in time.

The state of regulations vary from country to country, but fliers in any locality must also be aware of the restrictions on flying in the national airspace that may have been imposed by the civil aviation authority that covers subsections of the airspace or that restrict how or where an UAS may be flown. This includes restrictions on flights near airports and aircraft routes, flights over populated or urban areas and maximum and minimum flying heights over ground level. A common limitation is to restrict flights to areas that are within visible line-of-sight of the UAS pilot.

UAS are not a panacea for all mapping problems. Satellites, high-altitude photogrammetry, fixed-ground, mobile terrestrial and manned aircraft LiDAR, and ground-based techniques all have their place, especially when large areas are to be mapped at widely spaced time intervals. But geospatial data managers will be surprised to see how nagging problems as well as some they didn’t recognize as problems can be solved with UAS-based mapping

(4 votes, average: 1.25 out of 5)

(4 votes, average: 1.25 out of 5)

Leave your response!