| Applications | |

Deeds and titles in harmony: Trinidad and Tobago property business registration system

This paper outlines the innovative Property Business Registration System (PBRS) project to migrate separate deeds and titles registers into a single land information system and discuss some of the practical aspects |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Abstract

The Property Business Registration System (PBRS) project is an initiative of the Ministry of the Attorney General and Legal Affairs in Trinidad and Tobago to develop a land information system. The project will bring separate deeds and titles registers into a single harmonized, Land Administration Domain Model compliant, system.

This paper will present some background to the dual systems of land registration administered by the Registrar General’s Department and the legal frameworks that govern them. It will consider the legal reforms necessary to improve efficiency of the systems and examine the difficulty in developing a land information system that complies with and enforces existing laws and regulations while supporting new laws that have been assented to but are awaiting proclamation. This paper will outline the innovative PBRS project to migrate separate deeds and titles registers into a single land information system and discuss some of the practical aspects.

Introduction

The Property Business Registration System (PBRS) project is an initiative of the Ministry of the Attorney General and Legal Affairs (MAGLA) of the Government of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago (GORTT) to develop a land information system that will provide a highly available secure application to govern, capture and manage all aspects of the real and personal property registration process including the separate deeds and titles registration systems and ancillary documents. The project will bring separate deeds and titles registers into a single harmonized, Land Administration Domain Model (LADM) compliant, system.

PBRS is financed under the Strengthened Information Management at the Registrar General’s Department (SIMRGD) project through an Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) loan which commenced in January 2014. The SIMRGD project is part of the Public Sector Investment Programme (Ministry of Planning and Development, 2019a) and falls under the Improving Productivity Through Quality Infrastructure and Transportation development theme of the National Development Strategy 2016-2030 (Ministry of Planning and Development, 2019b). Known as Vision 2030, the strategy provides a pathway for attaining developed country status by the year 2030 and includes the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

The Vision 2030 national vision, development themes, and goals were crafted against a background of declining performance in selected global indices over the period 2006 to 2016. Trinidad and Tobago’s Global Competitiveness Index ranking had decreased from 67 to 92. The Ease of Doing Business ranking had declined from 55 in 2006 to 97 in 2011, improved to 66 in 2014 and declined to 88 in 2016. The Index of Economic Freedom ranking had declined from 42 to 73. The Networked Readiness Index had fluctuated but ultimately changed little as the ranking moved from 68 in 2006 to 67 in 2016. The Corruption Perception Index ranking began as 79 in 2006, declined to 91 in 2011, improved to 72 in 2015, and declined again to 101 in 2016 (Ministry of Planning and Development, 2019b).

The SIMRGD project primarily aims to improve conditions for investment in Trinidad and Tobago (TT) by streamlining the property registration process. Two components are financed under the project, namely: Institutional Capacity Strengthening of the Registrar General’s Department (RGD); and Support to Strengthening Identification of Parcels and Persons in Property Registration. A secondary aim is to help detect and prevent land fraud, land corruption, and money laundering. Vision 2030 stresses the need to monitor and evaluate performance, project success will be partially measured against global indices such as those mentioned earlier.

In Trinidad and Tobago, the RGD Land Registry is responsible for property registration and the Survey and Mapping Division (SMD) of the Ministry of Agriculture, Land and Fisheries, is responsible for cadastral surveys and the cadastre.

The main activities of the PBRS project are to:

• Design, develop, and implement a single land information system to administer both deeds and titles registration

• Migrate and integrate data from the existing deeds registration Property Information Management System (PIMS) to the new unified land information system

• Migrate and integrate data from a contemporaneous external project to digitize title registration instruments MAGLA engaged a consortium led by IGN FI (and including GEOFIT and the University of the West Indies) to execute the high-velocity PBRS project over an ambitious schedule of 17 months beginning in December 2018, going live in February 2020, and completing the warranty period in May 2020.

This paper will present some background to the dual systems of land registration administered by the RGD and the legal frameworks that govern them. It will consider the legal reforms necessary to improve efficiency of the systems and examine the difficulty in developing a land information system that complies with and enforces existing laws and regulations while supporting new laws that have been assented to but are awaiting proclamation. This paper will outline the innovative PBRS project to migrate separate deeds and titles registers into a single land information system and discuss some of the practical aspects of doing this.

Context

The twin is land Republic of Trinidad and Tobago is an archipelago at approximately 11° North and 61° West lying between the Caribbean Sea and the North Atlantic Ocean, the southernmost nation of the Windward Islands of the Lesser Antilles. The islands are 130 km south of Grenada and 11 km off the coast of Venezuela. Experiencing a tropical climate, the islands usually escape the path of hurricanes but lie in a seismically active area and were rocked by a 6.9 magnitude earthquake in August 2018.

Trinidad and Tobago have a total land area of 5,130 km2 and total population (in 2018) of 1.39 million (World Bank, 2019a). This land area is about the same size as the second smallest state of the United States, Delaware. Trinidad and Tobago’s population is about one and a half times that of Delaware.

Trinidad and Tobago gained independence from the United Kingdom in 1962 and is a member of the United Nations and CARICOM. Recognised by the United Nations as one of the group of small island developing states (SIDS) that have their own peculiar vulnerabilities and characteristics, Trinidad and Tobago like other SIDS has limited ability to benefit from economies of scale and is vulnerable to a large range of impacts from climate change (United Nations, 2019). Unlike many Caribbean SIDS, Trinidad and Tobago’s economy is less reliant on tourism. It is one of the most prosperous countries in the Caribbean largely due to petroleum and natural gas production and processing.

Two legal frameworks for land registration have existed side-by-side in Trinidad and Tobago since the late nineteenth-century resulting in today’s dual systems of land registration. The Common Law (or Old Law) system is a deeds registration system and the RPA (Real Property (TT) Act of 1945) or Torrens system, is a titles registration system. The legal frameworks for these systems are discussed below.

The Parliament of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago comprises the President and two houses, the Senate, and the House of Representatives. A proposal for a new law or for amendments to an existing law, when introduced into a House of Parliament becomes known as a bill. After a bill has passed both houses, it is presented to the President for assent or approval. The grant of ascent converts the bill into an Act. An Act, although assented to, does not necessarily come into immediate operation. The commencement provision specifies when the Act is to come into effect. This may be the date of assent by the President, a date to be fixed by proclamation, a nominated date, or some combination of these to provide for different sections or parts to come into effect at different times.

The frequent delay between the assent and when the Act comes into force is often for the purpose of gathering the necessary resources to administer the law. Development of the PBRS of necessity, was based on existing laws but simultaneously had to support new laws that had been assented to but were awaiting proclamation.

Legal frameworks

British rule of Trinidad and Tobago began in 1802 and brought with it the British common law and statutory legal system. Later, as Britain began modernizing its statutes regarding land tenure and conveyancing in the mid-nineteenth century, so too did Trinidad and Tobago. Statutory modifications to common law conveyancing practices that were introduced from time to time to simplify and clarify conveyancing practice, were codified as the Conveyancing and Law of Property (TT) Act of 1939.

A deeds registration system covering common law conveyancing practices was introduced with records maintained by the Registrar General as set out in the Registration of Deeds (TT) Act of 1884. Similarly, a titles registration system for administering documents and titles pertaining to land was introduced by the Real Property (TT) Ordinance of 1889 that was revised as the Real Property (TT) Act of 1945. Land in Trinidad and Tobago is regulated by the foregoing laws and by the Registrar General (TT) Act of 1921 (all as amended) as well as The Constitution of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago of 1976.

The deeds system requires that the original title deeds of a land parcel be deposited in the Land Registry, as evidence of the land transaction. The law requires a twenty-year title search as evidence of good title to a land parcel and offers a would-be purchaser a record of evidence of the transactions on the land. Registration is voluntary except when required by lending institutions and there is no guarantee of the accuracy of the content in the documents registered. A cadastral plan of the land is not mandated. The deeds system is favored over the titles system for its relative simplicity of procedure and low cost of registration.

The titles system was introduced with the aim of removing perceived defects of the deeds system. For this system, a certificate of title is issued for every land parcel registered. Registration is voluntary except in the case of granted state land and the state guarantees the title to the land, but not the parcel boundaries. An approved cadastral plan of the land parcel is required for registration. Provisions are made for the transfer of lands already registered under the deeds system to the titles system. The titles system is viewed as including expensive, long, and tedious procedures.

Legal reform

By the 1950s, there were many complaints about undue delays in completing land transactions and about the deplorable condition of some of the land records maintained by the Registrar General (Land Tenure Center, 1992b). A system which was adequate for the needs of a plantocracy for recording a few hundred instruments each year had long ago been overwhelmed and by the 1980s, change was urgently needed.

Done and Robertson (1988) summarized the recommendations of a feasibility study carried out by Statskonsult in 1980 as follows:

1. Create a special administrative unit for land registration.

2. Establish an effective baseregister system for land registration which should comprise:

a. An unambiguous parcel definition;

b. A descriptive land record register;

c. A map system showing the position of land as part of the register.

Done and Robertson (1988) also noted that the Land Registration (TT) Act of 1981 “made provision for the extension of registered title to compulsory registration areas and for the establishment of a Land Commission to be responsible for adjudication of title and adjustment of boundaries.”

Reporting on the Property Law Reform package of 1981, the Land Tenure Center (1992b) noted that it comprised seven acts including the Land Registration (TT) Act of 1981 and the Condominium (TT) Act of 1981 and that they “were intended to replace more than twenty existing enactments that govern property dealings and inheritance in Trinidad and Tobago” and that the entire reform package was based on “certain significant departures from the existing law”, introduced through the Land Law and Conveyancing (TT) Act of 1981 as follows: Reduction to two of the number of estates capable of subsisting at law

• Limitation of the possibility of the creation of legal tenancies in common

• Creation of the statutory trust

The Land Tenure Center (1992b) criticized that “A case for this attempt at multiple, major organ replacement surgery on the statute book has never been satisfactorily made out.” The Land Tenure Center argued that the problems affecting operation of the system of land registration in Trinidad and Tobago were mainly related to the recording and retrieval of land transaction information and the consequential proliferation of informal arrangements for gaining access to land. The package was never proclaimed.

In 1992, a ten-month GORTT comprehensive land use rationalization study was carried out by the Land Tenure Center with support from the IDB as part of the Land Rationalization and Development Programme (LRDP). The programme sought greater realization of the agriculture sector potential in Trinidad and Tobago based on a stable and secure system defining the rights of access and use of the land with a view to attract investment (Land Tenure Center, 1992a). Objectives included: to study farmers in irregular possession of state land, to review legislation and institutional capabilities for processing and recording land transactions, and to develop options to improve the security of those acquiring rights to land and to reduce costs of these transactions involving both public and private land. An action plan was developed that proposed several projects.

The study recommended that the 1981 Property Law Reform Package not be implemented and that a new Land Registration Act be prepared drawing on the provisions of the Land Registration (TT) Act of 1981 but expressed in a more readable style. In summary, the following legislation was recommended:

• Land registration. To make titles registration compulsory and unambiguously referenced to a map and a unique parcel number. Reliance on Judges and the High Court to be reduced through alternative methods of dispute resolution.

• Land adjudication. To provide for systematic adjudication of all claims affecting land to achieve economies of scale and facilitate prompt compilation of the titles register while removing routine title registration matters and boundary disputes from the High Court.

• Land tribunal. To establish a specialized, lay, Land Tribunal to resolve disputes concerning land-related issues speedily and inexpensively. • Land surveying. To provide for registration of land surveyors and regulation of their practice.

• Condominium. To provide for multiple ownership of property based on a company law model.

• Town and country planning. To provide greater clarity about the nature of the powers and the manner of their exercise by the Minister and officers of the Ministry.

Based on the study’s recommendations, the “Land Package” of the Land Adjudication (TT) Act of 2000, Land Tribunal (TT) Act of 2000, and Registration of Titles to Land (TT) Act of 2000 were all debated together and then assented in 2000 (Parliament of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago, 2018). The Land Registration (TT) Act of 1981 was repealed.

Although the three Acts are awaiting proclamation, they have all been significantly revised through the Land Adjudication (Amendment) (TT) Act of 2018, Land Tribunal (Amendment) (TT) Act of 2018, and Registration of Titles to Land (Amendment) (TT) Act of 2018. These amendments are all awaiting proclamation.

PBRS data model

The LADM, the ISO 19152:2012 international standard (Lemmen, Van Oosterom, & Bennett, 2015), was used as the starting point for the PBRS database design. The third-party software underlying PBRS, Innola, extends and adapts the conceptual LADM to develop a Trinidad and Tobago country profile with due regard for project requirements and international good practice. The PBRS re-engineered workflows, transactions, and database must be flexible enough to support both existing Common Law and RPA legislation. Furthermore, they must support some new laws that have been proposed but are awaiting assent and/or proclamation. For example, the adjudication of all land provided in the Land Package resulted in the PBRS being modified to introduce additional attributes on land parcel data which allow identification of which parcels are under adjudication or have completed adjudication. These designations will support future transactions and business rules to be introduced to manage these lands appropriately within PBRS.

However, anticipating new laws in software development brings with it the risk of rework. The software framework is designed to be able to support new laws or amendments to existing laws as and when they are proposed, assented, and proclaimed.

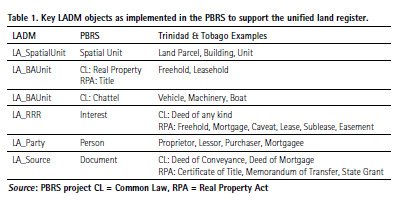

Table 1 shows the key LADM objects as implemented in the PBRS to support the unified land register. All instruments are registered as a deed interest type under Common Law. It is important to emphasize that there are not separate tables to manage these key objects for deeds and titles data. The single set of person table(s) support the unified register thus allowing a search on a unique person which results in all interests or transactions for which that person is party to regardless if related to deeds or titles. This may be enhanced by a proposed new requirement to use the birth personal identification number assigned by the RGD Civil Registry on the birth certificate. A unique identifier for foreignborn persons is still under consideration.

To simplify database searches for end users, objects are attributed appropriately to filter searches for a deeds or titles relationship. Document/Instrument names are harmonized to better support searches; that is a Deed of Mortgage and a Memorandum of Mortgage are both referred to as a Mortgage in PBRS but are attributed such that searches can distinguish between those which are deeds or which are title instruments, and provide this information back to the user. Another example is that spatial units are attributed as derived either from Common Law or RPA.

CL = Common Law, RPA = Real Property Act

The Doing Business report measures business regulations and their enforcement across 190 economies (World Bank, 2019b). The report provides quantitative indicators for several regulatory environments as it applies to local firms and encourages economies to compete towards more effective regulation and offers measurable benchmarks for reform. Perhaps the most relevant indicator to implementation of PBRS is known as registering property. This indicator examines four component indicators: procedures, time, cost, and the quality of land administration in each economy.

The reliability and objectivity of the report’s measurements has been questioned and caution should be used when comparing between regions and between countries as the methodology may vary. Rankings should be interpreted with care. The name of several indicators overstates what they measure. For example, registering property measures the procedures to transfer the property title of land and a building between two businesses, and not the procedures to obtain a title for the property for the first time. The World Bank Group recognises the limitations of the measurements (see also Acemoglu, Collier, Johnson, Klein, & Wheeler, 2013) but asserts that “The report measures complex regulatory processes by zeroing in on their quantifiable components, which can be contested, compared– over time and across economies– and, ultimately reformed” and offers “policy makers a tool to identify good practices that can be adopted within their economies” (World Bank, 2019b).

Doing Business 2019: Trinidad and Tobago (World Bank, 2019c) gives detailed results for the five indices that make up the quality of land administration index: reliability of infrastructure, transparency of information, geographic coverage, land dispute resolution, and equal access to property rights.

As mentioned above, the Land Registry is responsible for property registration and SMD is responsible for cadastral surveys. Trinidad and Tobago scores 4.0 out of 8.0 for reliability of infrastructure. Most topical title or deed records are kept as scanned images. Most maps of land plots are kept as scanned images and there is an electronic database for recording boundaries, checking plans, and providing cadastral information. However, title or deed records and maps of land plots are not yet fully digital, and information recorded by the Land Registry and SMD is kept in separate (unlinked) databases. The Land Registry and SMD do not use the same identification number for properties.

The need for a unique property identifier for Trinidad and Tobago has been recognised since at least 1980 (Done & Robertson, 1988) and the Registration of Titles to Land (TT) Act of 2000 establishes the use of a unique parcel reference number (UPRN) as the legal description of the parcel. Although this Act is awaiting proclamation, SMD anticipated the UPRN requirement by implementing a unique parcel identification number (UPIN) in their Cadastral Management Information System (CMIS). The Land Registry included provision for a UPRN in the PIMS deed registration system but never implemented it. Although the PBRS does not manage the spatial data related to land parcel spatial units, the database has been designed to support the UPIN assigned and managed by the SMD.

Implementation of PBRS has provided a window of opportunity for the Land Registry and SMD to collaborate to realise the full benefits of this unique identifier as the vital key to enable critical linkages between the register and cadastral data and to other land management data and systems to facilitate cross-government decisionmaking. At the very least, it will allow PBRS to integrate a display of a land parcel map for which SMD is the owner. Implementation of PBRS may encourage proclamation of all or part of the Land Package.

Other standardization proposed for the PBRS, but not yet finalized, is the adoption of the Trinidad and Tobago Postal Corporation (TTPost) addressing standard. TTPost, together with the Ministry of Public Utilities, the Ministry of Local Government along with its Municipal Corporations and the Tobago House of Assembly, is implementing the internationally recognised Universal Postal Union’s S-42 Addressing Standard, with postal codes throughout Trinidad and Tobago (TTPost, 2020). Although property addressing responsibilities and requirements are not legislated, adoption of the TTPost addressing standard will help to accurately identify persons and spatial units.

PBRS transactions and processes

Although the database is unified, the workflows and transactions for deeds registration and subsequent registrations on titles are separate and unique. The workflow and number of tasks for subsequent registrations on titles (e.g. mortgage, easement, lease) reflect the rigor required for review and approval of these registrations versus a deeds registration workflow which has fewer tasks to achieve a completed legal recordation.

The implementation of the PBRS transactions and the unified land register is complicated by the fact that Common Law still governs many prerequisite transactions for subsequent actions on a title under the RPA. The PBRS business rules and data entry are therefore configured to establish any required relationships. For example, a Substitution of Name (change of person name not due to marriage) transaction under RPA requires that the name change first be registered as a deed poll, and the instrument number of the registered deed is linked to the Substitution of Name. In addition, since a title registration applies to the land only, the registration of rights on dwellings (units, condominiums) constructed on that land are executed as a lease or sublease and registered as a deed, while also referring to the titled property in the titles register. For the lessor of that unit to have rights to common land areas on the titled land, an easement lease is registered against the title and linked to the registered lease deed. If a mortgage is registered against the lease interest, a collateral mortgage is also registered against the easement interest. There is no condominium legislation in force.

There are many other examples in current practice and in proposed law, which bind the registration of deeds to subsequent registrations on titled land. Further there are land policies, which apply to both deeded property and titled property in the same manner but must be implemented in PBRS as separate workflows and transactions in order to manage the interests and relationships properly. An example is the requirement to receive approval from the Attorney General for the late registration (after 12 months) for the conveyance of land as a gift.

PBRS legacy data verification and cleansing

The value of the unified land register database will not be fully realized until the deeds register data from the PIMS and the recently digitized titles, are thoroughly verified and cleansed after migration to the PBRS. There are two specific data objects which will require cleansing over time: the “person” data and the “spatial unit” data. Current data sources have many duplicates for the same person (natural or legal) and for the same spatial unit. Without cleansing, automated business rules cannot be implemented as desired, and searches are much more time consuming for both staff and public users. Ideally, there will be one active record for a person and one active record for a spatial unit. Verification and cleansing will be complex and tedious since there is no unique identifier for persons or parcels. The PBRS will support data verification and cleansing through various configured transactions. However, in order to maintain the accuracy of person data, submitting attorneys must change their practices and be required to use birth personal identification number for certain parties of transactions, and ideally use standard spatial identifiers (UPIN and TTPOST assigned address) as specified by the RGD for land parcels in their prepared instruments.

Performance

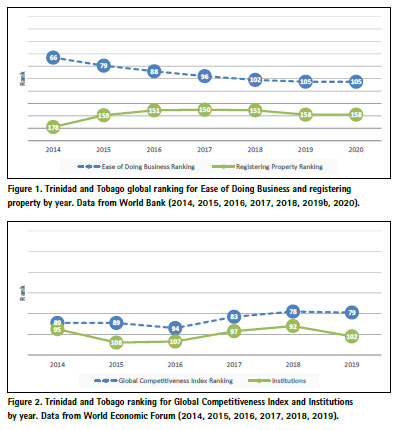

Six years after the start of the SIMRGD project, it is worthwhile to briefly examine performance against two of the global indices that prompted change: The Ease of Doing Business and the Global Competitiveness Index. Figure 1 shows that Trinidad and Tobago’s Ease of Doing Business ranking has continued to decline from 2014. Figure 1 also shows that during the same period, although the registering property indicator ranking was much lower than the Ease of Doing Business ranking, there was considerable (uneven) improvement.

The analysis presented in the Global Competitiveness Report produced by the World Economic Forum “is based on a methodology integrating the latest statistics from international organisations and a survey of executives.” The report is “designed to help policy-makers, business leaders and other stakeholders shape their economic strategies in the era of the Fourth Industrial Revolution.” The main ranking is known as the Global Competitiveness Index and measures national competitiveness defined as the set of institutions, policies and factors that determine the level of productivity. The index is organized into 12 pillars: Institutions, Infrastructure, ICT adoption, Macroeconomic stability, Health, Skills, Product Market, Labour Market, Financial system, Market size, Business dynamism, and Innovation capability (World Economic Forum, 2019).

Perhaps the most relevant pillar to implementation of PBRS is Institutions. This pillar includes components such as Efficiency of legal framework in settling disputes, Property rights, and Quality of land administration. Figure 2 shows that Trinidad and Tobago’s Global Competitiveness Index ranking has improved since 2014.

Figure 2 also shows that during the same period, the Institutions pillar ranking was lower than the Global Competitiveness Index ranking and that overall there has been a decline since 2014. Trinidad and Tobago ranks 79th overall, down one place from 2018. Its score has improved (58.3, +0.4 points) but dropped one place due to the addition of Barbados (58.9, 77th) to the ranking. Trinidad and Tobago’s performance is below the Highincome group average for all pillars but its relative strengths include ICT adoption (60.4, 61st), Macroeconomic stability (88.9, 58th), and Financial system (67.9, 45th), all with a positive trend. Trinidad and Tobago’s three main weaknesses are Institutions (47.9, 102nd), Product market (46.4, 122nd), and Market size (40.5, 106th). Institutions and Product market also show a negative trend.

Conclusion

The two global indices examined in this paper show some reasons to be optimistic about the success of the SIMRGD. Over the six years, the registering property indicator ranking, and the Global Competitiveness Index ranking have both improved. The Institutions ranking was improving but suffered a setback in 2019 that requires further investigation to determine the cause.

There are other reasons to be optimistic. Implementation of the PBRS will bring separate deeds and titles registers into a single harmonized, LADM compliant, system, thus achieving the goal of strengthening identification of parcels and persons in property registration. It will also contribute to detection and prevention of land fraud, land corruption, and money laundering. Successful implementation of the UPIN in the PBRS will make it possible to link the Land Registry and SMD databases for the first time thus improving the Doing Business reliability of infrastructure indicator, the quality of land administration index, and the registering property indicator. Once the PBRS is operational, land transactions will become faster and this, together with the proclamation of assented laws, is likely to boost the global indices. In the longer term Trinidad and Tobago may attract more investment.

References

Acemoglu, D., Collier, P., Johnson, S., Klein, M., & Wheeler, G. (2013). “A Review of Doing Business.” Retrieved from https://www.doingbusiness.org/ content/dam/doingBusiness/media/ Methodology/Open-Letter-Reviewof- the-Arguments-on-DB.pdf.

Condominium (TT) Act of 1981. Retrieved from http://laws.gov.tt/ ttdll-web/revision/byunprocliamed

Conveyancing and Law of Property (TT) Act of 1939, Chapter 56:01. Retrieved from http://rgd.legalaffairs.gov.tt/laws2/ alphabetical_list/lawspdfs/56.01.pdf

Done, P. & Robertson, M. M. (1988). A Northern Hemisphere Post- Colonial Cadastral System: Trinidad. Australian Surveyor 34(1). Available from https://www.tandfonline.com

Land Adjudication (TT) Act of 2000. Retrieved from http://laws.gov.tt/ ttdll-web/revision/byunprocliamed

Land Adjudication (Amendment) (TT) Act of 2018. Retrieved from http:// laws.gov.tt/ttdll-web/revision/byyear

Land Law and Conveyancing (TT) Act of 1981. Retrieved from http://laws.gov. tt/ttdll-web/revision/byunprocliamed Land Registration (TT) Act of 1981. Retrieved from http://laws.gov.tt/ ttdll-web/revision/byunprocliamed

Land Tenure Center. (1992a). Land Rationalization and Development Programme: Final Report. (Volume 1). Trinidad and Tobago Ministry of Agriculture, Land, and Marine Resources. Retrieved from https://books.google.com

Land Tenure Center. (1992b). Land Rationalization and Development Programme: Annexes. (Volume 1). Trinidad and Tobago Ministry of Agriculture, Land, and Marine Resources. Retrieved from https://books.google.com

Land Tribunal (TT) Act of 2000. Retrieved from http://laws.gov.tt/ ttdll-web/revision/byunprocliamed

Land Tribunal (Amendment) (TT) Act of 2018. Retrieved from http://laws. gov.tt/ttdll-web/revision/byyear

Lemmen, C., Van Oosterom, P., & Bennett, R. (2015). Land Administration Domain Model. Land Use Policy, 49, 535-545. Retrieved from http://www. gdmc.nl/publications/2015/Land_ Administration_Domain_Model.pdf

Ministry of Planning and Development. (2019a). Public Sector Investment Programme. Retrieved from https://www.finance.gov. tt/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/ PUBLIC-SECTOR-INVESTMENTPROGRAMME- 2020.pdf.

Ministry of Planning and Development. (2019b). The National Development Strategy of Trinidad and Tobago 2016- 2030. Retrieved from https://www. planning.gov.tt/content/vision-2030.

Parliament of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago. (2018). Bill Essentials: The Land Adjudication (Amendment) (No.2) Bill, 2017; The Land Tribunal (Amendment) (No.2) Bill, 2017; The Registration of Titles to Land (Amendment) (No.2) Bill, 2017. Retrieved from http://www. ttparliament.org/documents/2649.pdf

Real Property (TT) Act of 1945, Chapter 56:02. Retrieved from https://rgd.legalaffairs.gov.tt/laws2/ alphabetical_list/lawspdfs/56.02.pdf

Real Property (TT) Ordinance of 1889. Not available. Registrar General (TT) Act of 1921, Chapter 19:03. Retrieved from https://rgd.legalaffairs.gov.tt/laws2/

Alphabetical_List/lawspdfs/19.03.pdf Registration of Deeds (TT) Act of 1884, Chapter 19:06. Retrieved from https://rgd.legalaffairs.gov.tt/laws2/ Alphabetical_List/lawspdfs/19.06.pdf Registration of Titles to Land (TT) Act of 2000.

Retrieved from http://laws.gov. tt/ttdll-web/revision/byunprocliamed Registration of Titles to Land (Amendment) (TT) Act of 2018.

Retrieved from http://laws.gov. tt/ttdll-web/revision/byyear

The Constitution of The Republic of Trinidad and Tobago of 1976. Retrieved from http://rgd.legalaffairs. gov.tt/Laws2/Constitution.pdf TTPost. (2020). Postal Code Implementation. Retrieved from https:// ttpost.net/index.php/news/postal-code/ United Nations. (2019). “Small Island Developing States.” Retrieved from https://sustainabledevelopment. un.org/topics/sids/list

World Bank. (2014). Doing Business 2014: Understanding Regulations for Small and Medium- Size Enterprises. World Bank Group. Retrieved from http://www. doingbusiness.org/en/reports/globalreports/ doing-business-2014.

World Bank. (2015). Doing Business 2015: Going Beyond Efficiency. World Bank Group. Retrieved from http:// www.doingbusiness.org/en/reports/ global-reports/doing-business-2015.

World Bank. (2016). Doing Business 2016: Measuring Regulatory Quality and Efficiency. World Bank Group. Retrieved from http://www. doingbusiness.org/en/reports/globalreports/ doing-business-2016.

World Bank. (2017). Doing Business 2017: Equal Opportunities for All. World Bank Group. Retrieved from http://www.doingbusiness. org/en/reports/global-reports/ doing-business-2017.

World Bank. (2018). Doing Business 2018: Reforming to Create Jobs. World Bank Group. Retrieved from http:// www.doingbusiness.org/en/reports/ global-reports/doing-business-2018.

World Bank. (2019a). “World Development Indicators.” Retrieved from https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/ dataset/world-development-indicators.

World Bank. (2019b). Doing Business 2019: Training for Reform. World Bank Group. Retrieved from http:// www.doingbusiness.org/en/reports/ global-reports/doing-business-2019.

World Bank. (2019C). Doing Business 2019: Trinidad and Tobago. World Bank Group. Retrieved from http:// www.doingbusiness.org/content/ dam/doingBusiness/country/t/ trinidad-and-tobago/TTO.pdf.

World Bank. (2020). Doing Business 2020. World Bank Group. Retrieved from http://www.doingbusiness.org/en/reports/ global-reports/doing-business-2020. World Economic Forum. (2014). The Global Competitiveness Report 2014-2015. Retrieved from http://reports.weforum.org/ global-competitiveness-report-2014-2015/.

World Economic Forum. (2015). The Global Competitiveness Report 2015-2016. Retrieved from http://reports.weforum.org/ global-competitiveness-report-2015-2016/.

World Economic Forum. (2016). The Global Competitiveness Report 2016-2017. Retrieved from https:// www.weforum.org/reports/the-globalcompetitiveness- report-2016-2017-1

World Economic Forum. (2017). The Global Competitiveness Report 2017-2018. Retrieved from https:// www.weforum.org/reports/the-globalcompetitiveness- report-2017-2018.

World Economic Forum. (2018). The Global Competitiveness Report 2018. Retrieved from http://reports.weforum. org/global-competitiveness-report-2018/.

World Economic Forum. (2019). The Global Competitiveness Report 2019. Retrieved from http://reports.weforum. org/global-competitiveness-report-2019/.

The paper was prepared for presentation at the “2020 World Bank Conference On Land And Poverty” The World Bank – Washington DC, March 16-20, 2020. Copyright 2020 by author(s).

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)

Leave your response!