| Navigation | |

Satellite Navigation– Truths & Myths

|

||||

|

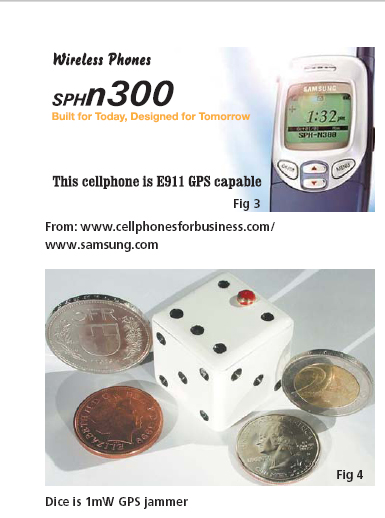

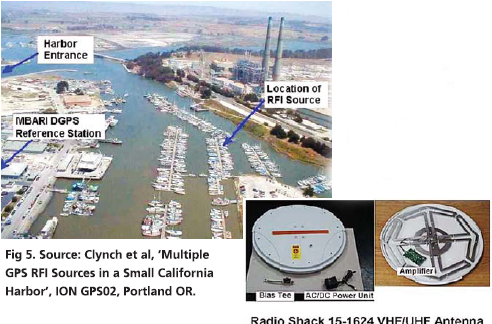

Today’s professional navigators may well be the last. As recently as a generation ago, navigation was almost solely the specialised art of a small number of highly-skilled people. They wore uniforms with emblems on their shoulders. They had years of training.They used complex, expensive, equipment. They bestrode the bridges of ships and the fl ight decks of the large commercial aircraft and took star shots. Then, quietly, a revolution started in the world of navigation. The first phase of the revolution brought lower cost, smaller, higher performance navigation equipment. Amateur sailors and aviators got technology more powerful than professional equipment, and very much cheaper: Decca Navigator and Loran-C sets for yachts, for example (Fig 1 & 2). The second phase of this revolution was driven by GPS. Navigators, the early adopters of satellite navigation, were rapidly followed by surveyors, geodesists, desert travellers – people with at least loose connections to navigation. But then came, farmers,motorists, truckers, people seeking not so much the high peaks of the great outdoors as the delivery bay at McDonalds! Soon, these nonnavigators outnumbered the navigators.Global navigation systems stopped being primarily about navigation; they became simply public utilities. And now we are entering a third phase of this revolution, where the utility that is Global Satellite Navigation becomes universal and largely invisible. The trigger for this phase was the US government’s requirement that cell-phone networks should automatically identify the locations of users who call the emergency 911 number. Many networks chose Assisted-GPS (A-GPS) technology, nearinstantaneous location measurements using a GPS receiver inside the handset, assisted by data passed to it over the cellular system (Fig3). This works, and the networks can now locate their users. Your phone can tell you where you are, download a map for you, guide you to your destination; it can locate the nearest police station, or hospital, pubs for young men and toilets for elderly gentlemen. It can give you tourist information, tell you of traffi c problems ahead. Phones can track your children or your girlfriend, or your boyfriend! Of course, think of the Internet and spam: as you walk down a street, your phone will soon try toentice you into sleazy bars, dubious cinemas, or houses of ill repute! Worldwide, there will be soon be hundreds of millions of new users of global satellite navigation systems, GNSS. Most of them will neither know nor care that they are using a satellite navigation system. Our sophisticated navigation technology will simply have become a location sub-system of a low-cost consumer product. Have navigators, institutes of navigation, or national governments yet come to understand this new reality? Do we not still think in traditional navigation terms, of ships and aircraft alone? Look, for example, at how we are responding to the current threat of the possible loss of satellite navigation. On September 10, 2001, the day before 9-11, the Volpe Report was published. This US government document speaks in clear terms of the risks the US takes if GPS becomes its only means of navigation, or (as it is becoming) the only source of the precision timing that synchronises US telecommunications networks. The risk is partly from interference, unintentional or intentional. Volpe says such interference hazards can be reduced, but never eliminated. And with US transportation relying increasingly on GPS, losing it could cause severe safety and economic damage to the nation, unless those threats are somehow mitigated. The report says that GPS is becoming a tempting target for individuals, groups, or countries hostile to the US. GPS can be denied by jamming, and receivers can even be spoofed into producing hazardous, misleading information. So, the Volpe Report calls for awareness, planning, and supplementing GPS with backup systems in critical applications a tempting target for individuals, groups, or countries hostile to the US. GPS can be denied by jamming, and receivers can even be spoofed into producing hazardous, misleading information. So, the Volpe Report calls for awareness, planning, and supplementing GPS with backup systems in critical applications the satellite signals at 85km. A more sophisticated jamming signal would be effective to maybe 1000km. Such a jammer on the roof of a tall building could stop every GPS across a city: car navigators, tracking systems in taxis and fi re trucks, and receivers in aircraft within line of sight. If the jammer were left on, and perhaps moved occasionally to make it harder to fi nd, it would begin to affect GPStimed telecommunications systems. Cell-phone sites, and telephone and data communications that employ local GPS timing, would gradually drift out of synchronisation and fail. Who would deal with the problem? Would the US Cavalry come riding over the hill? We must ask in each country: who has the equipment to fi nd a civil jammer, the organisation to respond, and the legal powers to enter buildings and search for it? In most countries: no-one. Jamming problems are real. In the harbour of Moss Landing in California, a couple of faulty TV antenna units on boats radiated interference (Fig 5). Every vessel in the harbour, and up to a kilometre out to sea, lost GPS service. So did every vehicle and every individual. A few GPS receivers actually gave false positions. The problem lasted for months until the cause was tracked down by technicallycompetent volunteers. There are millions of such TV amplifi ers across the world. These units are not designed to jam GPS, but their malfunctioning can result in a 3 km jamming range. Imagine a jammer purposebuilt by an expert! GPS jammers have a lot |

||||

Pages: 1 2

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)