| Applications | |

Jahan Jhuggi Wahan- Makaan: In-situ Slum Rehabilitation

The Central and State governments have committed the policy of Jahan Jhuggi-Wahan Makaan, that is In-Situ Slum Resettlement in Delhi, replicating the Dharavi Model of Mumbai. While the policy is already mandated in the Delhi Master Plan, its implementation involves putting in place people centric, evolutionary and support-based tools that are more longitudinal and avoid the providers’, vertical model. This paper seeks to address the theme of the World Habitat Day (6 October 2025)-Urban Crises Responses and Localisation. |

|

|

Slums in Delhi are an inseparable part of the national Capital with residents living there for decades. An immediate halt to demolition drives in the Capital’s slum clusters and if unavoidable all future removals will be accompanied by advance rehabilitation.

Delhi Chief Minister, Rekha Gupta (1st August 2025)

Conventional planning approaches to slums and slum dweller are thoroughly paternalistic. The trouble with paternalistic is that they want to make impossibly profound changes and they choose impossibly superficial means for doing so. To overcome slums, we must regard slum dwellers as people capable of understanding and acting upon their own self-interests, which they certainly are.

Jane Jacob

During the Delhi Assembly elections (2025) the Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced the policy of Jahan Jhuggi -Wahan Makaan for Delhi. The Delhi Development Authority’s (DDA) f irst in-situ project at Kalkaji with 3024 f lats was inaugurated by the Prime Minister Narendra Modi in November 2023. The second project at Jailorwala Bagh with 1675 flats was inaugurated on 2nd January 2025. The Kathputli Slum Redevelopment Project with 2,800 flats in 14 storey towers for slum dwellers is nearing completion, which has been developed under the public-private partnership. According to the reply given in Rajya Sabha on 21st July 2025, out of 5,158 households living in the hutments in Kalkaji, Ashok Vihar, Rampura, Mata Jai Kaur and Kalabari, 3403 eligible households were allotted with the flats.

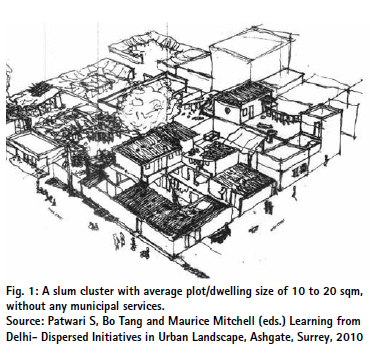

The Twentieth Century Dictionary of Chambers defines slum as an overcrowded, squalid neighbourhood. Here the word squalid is defined as ‘filthy, foul, neglected, uncared, unkept, sordid and dingy, poverty stricken.’ No word other than ‘slum’ suggests more terrible image of the poor man’s life. No word is more capable of rousing people to protest and shock the politician’s conscience. Slums are denounced everywhere, and the governments generally agree that the slums should be prevented and eliminated as soon as possible. However, the slums are inevitable products of urban development. Slum is an area, and not a building. It is characterised by absence of basic civic amenities and community facilities, by insanitation, filth, congestion, squalor and structural dilapidation of the tenements, that is blight (Fig. 1). Children sprawl in the dust or play in the drains, and on narrow lanes with their uneven surface. Cattle and human beings live together. Dirty gunny bag and curtains hanging from the doorways symbolise the futile striving for privacy.

The economic pull of the city results in inmigration of people for employment, who often tend to minimise rent costs by living in hutments and substandard dwellings- preferably near the place of employment. Once in the slums, the disinclination of the slum dwellers to move away makes it difficult to relocate the population in alternative housing areas because of low rents, strong community relationship and proximity to the place of work. However, the vitiated and constricted environment of the slums results into their demoralisation and robs their family of sustenance and energy. These also reflect the society’s economic structure, power relationship amongst social groups and political structure of the state. It impacts the employment patterns, urban- rural relationship, income distribution, gender equity and health of the population. Majority of the poor people living in slums suffer from a growing sense of frustration, as their lives, families and their hopes disintegrate. The need for secure and adequate shelter keeps growing with the population growth, urbanization, and mounting pressures of economy and competition.

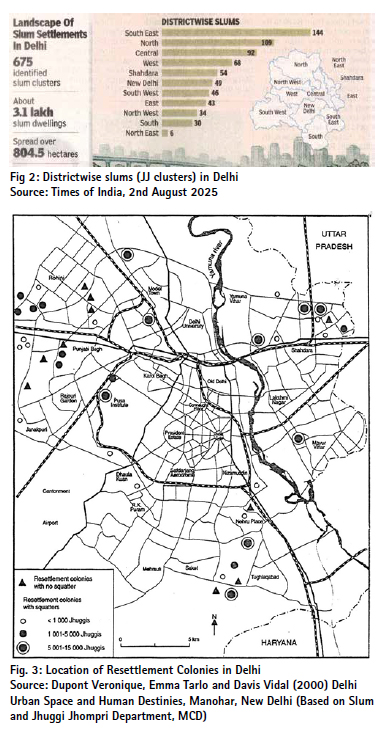

About one-eighth of Delhi’s population is living in about 675 slums and Jhuggi-Jhompri (JJ) clusters, covering about 1000 Ha of land. According to GNCTD Survey (2022) about 21.6 lakh people are living in about 4 lakh jhuggis /hutments (Fig. 2)

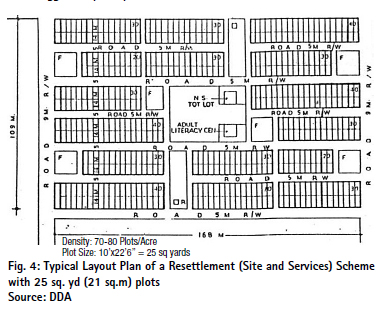

In Delhi’s planning parlance ‘slum’ is defines as an area unfit for human habitation. Slums are designated according to Slum Improvement and Clearance Areas Act of 1956. The notified slums are legal in status and are eligible to resettlement and range of services. Jhuggi-Jhompri settlements are seen as illegal encroachments on public and private lands. During the emergency (1975-77), a massive program of slum resettlement, covering 1.54 lakh plots of 21 sqm each (7 lakh people) living in the slums and Jhuggi-Jhompri (JJ) clusters was undertaken by the Delhi Development Authority (DDA) (Figs 3, 4 & 5). Touted as one of the world’s largest resettlement projects, DDA’s Slums and JJ Resettlement Programme during the Emergency (1975-77) attracted global attention and also created controversies. Earlier the resettlement colonies were under the purview of the Municipal Corporation of Delhi (1962-1974) and again during (1992-2010). Since 2010, these are with the Delhi Urban Shelter Improvement Board (DUSIB), under the Government of National Territory of Delhi. In 2016, the Delhi cabinet approved the Delhi Slum Policy. According to the policy, no jhuggi which has come up before January 1,2006 will be demolished, and those staying in slums till January 1, 2015 will be eligible for relocation in flats.

Slum Rehabilitation Scheme (SRS) in Dharavi, Mumbai

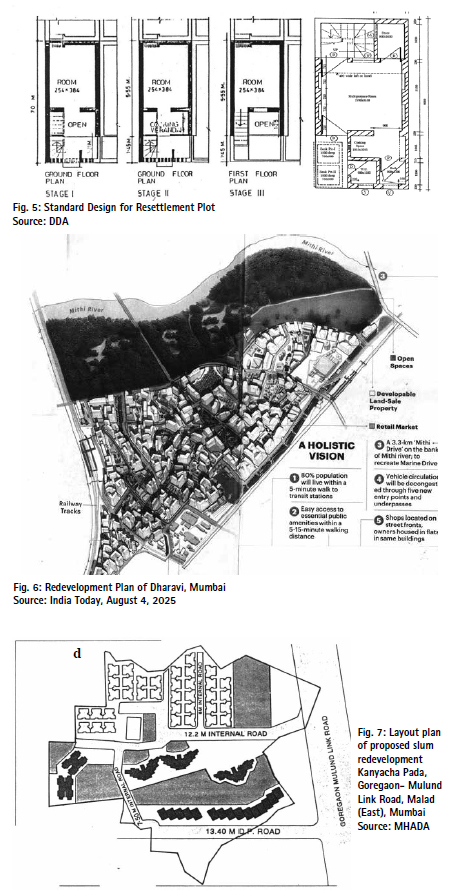

Dharavi in Mumbai covering 621 acres, is estimated to have about 1.2 million population, half of which is estimated to be eligible for resettlement. A plan for its redevelopment has been recently approved (2025-32) for building 1,05,000 f lats and 20,000 small commercial/ industrial spaces for the Project Affected Persons (PAP) (Fig.6).

The project is being implemented by Nav Bharat Mega Developers (P) Ltd, a Special Purpose Vehicle with the Government of Maharashtra, at an estimated cost of 2.5 lakh crore (May 2025). Based on “Public Private Partnership” (PPP), it aims to address the primary issue of right of slum dwellers to decent housing and also tenure rights and means of livelihood. On-site rehabilitation gives the slum dwellers access to basic civic amenities, besides promoting neighbourhood improvement. The slum dwellers are also required to provide maintenance charges.

The Government of Maharashtra has undertaken the redevelopment of Dharavi comprising as per the provisions of Maharashtra Slum Areas (Improvement, Clearance and Development) Act, 1971, and under the Regulation 33 (9) (A) and 33 (10) (A) of Development Control Regulations, 1991 for Greater Mumbai. The area has been divided into five sectors of which sector 1 to 4 are to be developed through private developers, who shall construct free housing for the eligible slum dwellers and occupants, including amenities and infrastructure as per the norms. In lieu the developer is entitled to construct free sale area, which he can sell in the market. The Floor Space Index (FSI) for the project is 4.0. The completion period of the construction of rehab, renewal, amenities and infrastructure is seven years from the signing of the development agreement.

A conceptual Master Plan for redevelopment of Dharavi incorporates the following:

• Integration of the residents into the mainstream • Interactions for livelihood and lifestyle within the community • Inherent flexibility of trade

• Non-rigid cohesive mixed use for efficient use of space

• Close interaction with community by developer. However, 70 per cent consent is no longer required since the project is implemented by the SRA

• Pedestrian dominant movement to tackle high densities; and

• High standards of specifications for the construction of buildings, amenities and infrastructure.

The development control regulations of Mumbai Municipal Corporation are given below:

• FSI: An FSI up to 2.5 to 4.0having a differential approach is allowed and the concept of Transfer of Development Rights (TDR) has been made applicable in order to avoid congestion and over-concentration in heavily built-up areas.

• Density: The minimum density prescribed for such development is 500 tenements per hectare. • Ground coverage – In Slum Rehabilitation/Redevelopment projects, the rule for ground coverage is confined to peripheral setbacks as per DCR without insisting upon overall ratio of ground coverage/plot size.

• Mixed land use: for Slum Rehabilitation in Mumbai, mixed land use policy has been adopted. Existing shop owners are eligible for built up shops up to 225 sq.ft. of area. The usual practice is to allow 10% of the FSI for commercial use in Cooperative Societies.

• Open Space: The practice is to reserve 15 per cent of the plot as open space.

• Community facilities: The provision of community facilities is generally seen as a government responsibility and the provision of community facilities in SRD schemes is not insisted upon, except essential utilities like electric sub-station, pump house, etc.

The construction is the responsibility of the developer, besides the development of the infrastructure, roads, water supply, sewerage, storm water drainage, rainwater harvesting, etc. The developer is expected to recover these costs from market sale component of the project. Several areas outside Dharavi have also been identified for slum rehabilitation as per the eligibility: a. Settled before January 1st, 2000 , free, b. between January 1st, 2000, to January 1st, 2011, at discounted rate, and c. between 1st January 2011 to November 15, 2022 (against actual cost).

The construction is the responsibility of the developer, besides the development of the infrastructure, roads, water supply, sewerage, storm water drainage, rainwater harvesting, etc. The developer is expected to recover these costs from market sale component of the project. Several areas outside Dharavi have also been identified for slum rehabilitation as per the eligibility: a. Settled before January 1st, 2000 , free, b. between January 1st, 2000, to January 1st, 2011, at discounted rate, and c. between 1st January 2011 to November 15, 2022 (against actual cost).

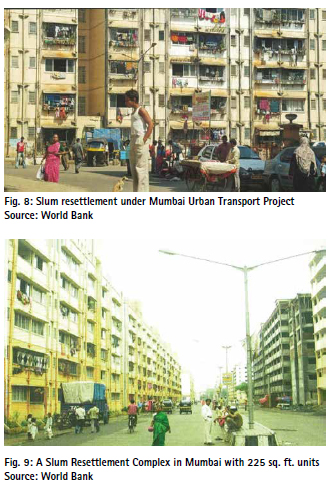

Resettlement of Slums under Mumbai Urban Transport Project

In 2002, the MHADA embarked the Mumbai Urban Transport Project (MUTP) with the help of the World Bank which aimed at improving the transport services in the city. The project required large scale resettlement of about 100,000 people or 17,500 households, some 1800 shops, and more than 100 religious and cultural properties, existing on railway, public and private lands and roads. There was a variety of such occupiers-legal landowners, ‘pagdi’ holders, tenants and lessees, as well as squatters without title, almost ninety-five percent without a legal title. Resettling of these people was undertaken in several resettlement sites in Mumbai where housing of 225sq.ft. each was built (Figs 7 to 9). Affected shopkeepers and landowners were also allowed to buy additional f loor area up to 525 sq.ft. in proportion to their loss.

Under the scheme, land has been used as a resource. Private developers were given additional transfer of development rights (TDR) or Floor Space Index (FSI) against building dwelling units for slum dwellers at their own cost. Landowners in affected areas were also offered TDR or additional FSI in lieu of cash compensation for the land they lost.

The MMRDA in consultations with residents and shopkeeper associations and the managing committees of the religious structures, explored alternative resettlement solutions, beyond the scope of R & R policy. The project implemented through MHADA, CIDCO & MMC, comprises 2 main components:

• Land Infrastructure Servicing Programme (LISP)

• Slum Upgradation Programme (SUP)

The NGOs provided support in the provision of common facilities, such as open spaces, lighting, lifts, internal roads, sanitation and drainage. Society management offices, day care centres and women centres were provided, besides community halls and health centres. A Livelihood Cell was set up to promote income generating activities for women at all the resettlement sites. A women industrial cooperative called SANKALP was formed to undertake a range of economic activities including supplying office stationery, selling vegetables and providing catering and housekeeping services.

MOUD Committee on Making Delhi Slum Free (Madhukar Gupta Committee, 2004)

The MOUD in 2004 constituted a committee with an object to draw a roadmap for making Delhi slum free. With VC Delhi as its Chair, the Committee had the Joint Secretary MOUD, Deputy Secretary (UD) GNCTD, Commissioner MCD, Additional Commissioner (Slums) MCD, Chairperson NDMC as the members and Commissioner (Planning) as its member Secretary. It also studied the Slum Resettlement Scheme and working of the Slum Rehabilitation Authority (SRA) in Mumbai.

According to Madhukar Gupta Committee Report the Slum Rehabilitation Scheme in Mumbai up to 2003 undertook the construction of about 2,10,000 tenements in 1040 schemes. The Committee noted that in Mumbai the system of de reservation of areas occupied by the slums was invoked that enabled redevelopment of slums in non-conforming land use. Whether this can be extended in Delhi needs to be examined with reference to various court orders and Delhi Development Act, 1957. Another contentious issue was that of ‘eligible and ineligible’ slum dwellers for rehabilitation. The SRA in Mumbai grants building permissions under the Development Control Regulations which covers the following:

• DCR-30 (10) Scheme In-situ rehabilitation/redevelopment

• 3-D Schemes Relocation of squatters from road/railway/ airport/ROW

• 33.14 Transitory shifting/ accommodation of JJ units on rental basis

The Committee observed that the JJ clusters existing up to January 1, 1995 were eligible for rehabilitation if at least 70% residents agree, and cooperative housing society of slum dwellers is formed. Each slumdweller is given a dwelling unit (DU) of 20.9 sm carpet area or 25 sqm of covered area. Over and above the FAR required for rehabilitation, equivalent FAR is permitted for free sale component, with a maximum FAR of 250 (later revised to 400). Transfer of Development Rights (TDR) is allowed for free sale component which can be utilise elsewhere. A density of 500 DUs per hectare and 25% ground coverage were allowed. Each scheme was also permitted to have a Society office, Balwadi and Welfare Centre @ 20.9 sqm for every 100 JJ units, which are not counted the FAR. The developer has also to deposit maintenance charges as prescribed by the SRA. Rehab tenements cannot be sold for a period of ten years but can be transferred to a legal heir. Based on the Mumbai Model, the Committee suggested the following two rehabilitation models for Delhi:

a. Involvement of private sector, broadly on the Mumbai pattern, where a part of the land for slum rehabilitation is made available to the private sector for market sale

b. Slum rehabilitation by the Slum Cooperative Societies as a joint venture with the land-owning agency and/or private sector.

The Committee also observed that presently there is no comprehensive data base of the slums and neither there is a way to find out if the relocation tenement/plot has been transferred. In this context, the Committee suggested that agency-wise encroachments on public lands need to be GIS surveyed, inventorised and monitored on a regular basis.

The Committee noted that notwithstanding the importance of the nexus between JJ clusters and place of work, it would not be practical to find relocation sites near the workplaces and existing slum clusters, or to establish an artificial linkage between the workplaces, existing slums and their rehabilitation. A more practical approach would be mixed land use in and around the slum rehabilitation areas.

To determine whether a squatter/JJ Cluster is eligible for in-situ rehabilitation or relocation- the Committee proposed the following multiple index system:

a. In-Situ Slum Rehabilitation criteria will not be applicable for the slum/JJ clusters in the regional park/ridge, high security zone, heritage conservation zone, MRTS Corridors, and environmentally and ecological sensitive areas.

b. The maximum size of individual plots/hutment/dwelling for rehabilitation shall not be more than 20 sqm, to ensure that the poor population is covered and not the well to do encroachers.

c. The eligibility of in-situ rehabilitation shall be based on the following multiple index:

i. Land Use (As per MPD/Zonal Plan)

ii. Density/Congestion iii. Services

iv. Security and Location Safety (Environmental, Fire and Flood, etc.)

v. Condition of Structures

These factors will assess the choice of in-situ rehabilitation or relocation that includes the options of redevelopment, upgradation, re-blocking, retrofitting and reconstruction, which will be determined on the basis of survey of existing condition of services and structures.

• The land-owning agency shall be bound by the policy of rehabilitation and resettlement, Land Acquisition Act, Master Plan (DCR) stipulations and transfer the ownership of land to the designated agency for slum and JJ rehabilitation/ local authority/development authority, as the case may be.

• The financial investments shall be shared by the concerned designated agency, land owning agency and infrastructure service agency, according to the policy in vogue. Part of the site may be developed for market sale residential use, including 10 per cent of FAR for commercial use to subsidise the project. However, market sale component shall not exceed 40 per cent of total permissible FAR.

• The planning and design shall be based on optimum utilisation of land as per Master Plan Norms.

Slum Redevelopment Norms in Master Plan for Delhi-2021 (MPD-2021)

Based on the Madhukar Gupta Committee Report (2004), the following norms for in-situ slum rehabilitation have been stipulated in MPD-2021:

i. Minimum plot size 2000 sqm (facing a min. road of 9m).

ii. Density – 600 to 900 units per hectare.

iii. The scheme should be designed in a composite manner with an overall maximum FAR of 400

iv. Mixed land use/commercial component up to 10% of permissible FAR.

v. Specific situations may require clubbing of scattered squatters with JJ sites in the neighbourhood to work out an overall comprehensive scheme.

vi. The minimum component of the land area for rehabilitation of squatters has to be 60% and maximum area for remunerative use has to be 40%.

vii. Area of dwelling unit for rehabilitation shall be around 25 to 30 sq.m.

viii. Common parking is to be provided which can be relaxed wherever required, except for the parking for remunerative purposes.

ix. No restriction on ground coverage (except set-backs)

x. There is no restriction on the height, subject to clearance of the Fire Department, Civil Aviation Department and Structural Safety. The development control norms facilitate both the options walk up (5 storeys) or multi storeyed apartments in order to achieve the full permissible density and floor area ratio.

xi. Schemes/designs should be compatible for disabled.

The Master Plan of Delhi (MPD 2021) allows the amalgamation of the plots to a minimum combined area of 1670 sqm with an FAR up to 400 and a minimum street width of 7.5 m. Additional floor area ratio (FAR) would motivate the owners of fragmented plots to form a cooperative for a composite redevelopment of illegal/unauthorised colonies into group housing, with proper roads, parks, parking spaces and safer structures. For grant of ownership rights in the unauthorised colonies, the MOHUA vide its notification dated 29th October 2019 enacted the NCT of Delhi (Recognition of Property Rights of Residents in Unauthorised Colonies) Regulations, 2019.

In-Situ Slum Redevelopment under the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (PMAY-Urban)

The In-Situ Slum Redevelopment Scheme under PMAY (Urban) recommends the following:

▪ Community mapping and enumeration of slum households

▪ Forging partnership among the communities for their participation in the decision making and planning

▪ Granting them occupancy and land rights

▪ Improving urban basic services, public transport, and social facilities

▪ Facilitating the access to finances and institutional home loans.

Till 2023, the PMAY (U) have been able to build and deliver more than 10.3 million houses, of which 4,90,260 dwelling units are under In Situ Slum Redevelopment Scheme. The Government of India and the BMTPC have taken up Lighthouse Projects under the PMAY (U) and its Slum Rehabilitation Scheme.

The Government of India and the BMTPC have taken up Lighthouse Projects under the PMAY (U) and its Slum Rehabilitation Scheme. These are based on provider’s model of the delivery of subsidised housing units built with prefab technology. These are built according to EPC (Engineering, Procurement and Contracting), and L-1 (lowest bid contracting) Systems. A question has been raised whether the multi-storied flats for slum dwellers make a house a commodity, ignoring the aspects of women, work from home, community formation and participatory, evolutionary housing development.

In-Situ Slum Rehabilitation Projects in Delhi

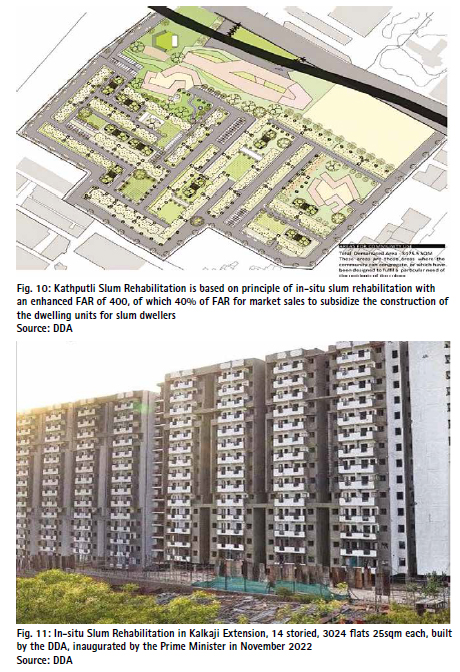

As stipulated in the MPD-2021, the Delhi Development Authority has been taken up several projects of in situ slum rehabilitation. The Kathputli Slum Rehabilitation project was one of the earliest of them, near Shadipur Depot, it covers 5.22 hectares of land and has been built with 2,800 EWS (Economically Weaker Section) flats for squatter families (30.5 sq.m. each) in 14 storey towers (Fig 10). This was based on the Mumbai Model of in-situ slum rehabilitation, as recommended by the Committee on Making Delhi Slum Free (2004) and MPD-2021. Planned Strategic Options under the public-private partnership, the project was announced in 2009 but was delayed due to many hurdles, such as court cases, disputes among the occupants, tenants and eligible/ ineligible residents, and political interventions. Part of the land has been used by the private developer for 170 freehold residential f lats and 16,800 sm of commercial space for market sale to make the project f inancially viable and to subsidize the construction of resettlement housing. Other in-situ slum resettlement projects of the DDA, covering about 33,000 resettlement flats, include Kalkaji Extension Phase I (inaugurated in November 2022, Fig. 11), Kalkaji Extension Phase II, Jailorwala Bagh (inaugurated in January 2025), Dilshad Garden, Shalimar Bagh, Pitampura, Suraj Park, Rohini, Badli Sector 19, Rohini, Rohini Extension Pooth Kalan, Haiderpur, Indira Kalyan Kendra, Okhla Phase I and 2, Govind Puri, Kalkaji, Kusum Pahadi, Vasant Kunj, and Kalyan Kendra.

Strategic Options

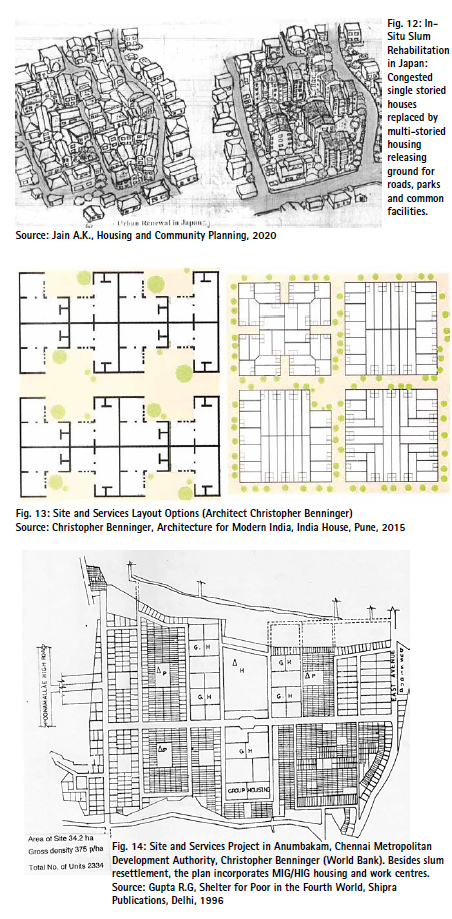

After six decades of planning and rehabilitation experience, Delhi has come a long way in the field of slum resettlement. It has shifted from Site and Services approach to provider’s model. However, the growth of slums continues unabated. The questions are raised- whether the slums are a problem or a solution? Can there be an alternative idea for slum redevelopment. Turner in his 1976 book ‘Housing by People: Towards Autonomy in Building Environments’ wrote that “only a minority can be supplied housing in centrally administered ways using centralising technologies, and then only at the expense of an impoverished majority and the rapid exhaustion and poisoning of the planet’s resources.” Since 1972, more than 70% of all the World Bank’s housing loans were for Sites and Services. However, it fell out of favour due to implementation issues. In 2022, the World Bank study ‘Reconsidering Sites and Services’ pleaded again for its revival. The greatest advantage of the site and services strategy is that it is rapid, low cost and provides freedom to the families to design their dwellings according to their needs, resources and tastes. As compared to the f lats in a multi-storied building, the site and services schemes facilitate connection with the ground, so important for the children, women and self-employed. The allottees f inance the cost of constructing their houses and part of the land cost, whereas the development agency provides the land and services. This way every house is an expression of the lifestyle of its dwellers, but within an organised framework and municipal services. These can also act as the powerful tools of poverty reduction. As suggested by Jane Jacob, Hernando de Sato, Christopher Benninger and Graham Tipple, the small shops and micro- businesses are the symptoms of inclusive growth and empower the informal sector.

According to the famous American thinker Jane Jacobs, ‘Planning for vitality must aim at unslumming the slums and clarifying the visual order of cities and it must do so by both promoting and illuminating functional order, rather than obstructing and denying it.’ Writing about the slum dwellers Christopher Benninger States: ‘this needs support from the planning and housing agencies, both governmental and non governmental, to enable them to always put the last person first, looking at the hutment dweller, the informal sector hawker, the physically challenged, domestic servants, rickshawalas, and casual workers. This requires seeking the paths and channels to support, facilitate and empower the poor citizens into becoming its stakeholders, thus harnessing their energies and amplifying their contribution. We need to examine the shelter, in a milieu where planning has safeguarded disproportionately for the elite segments of the society’.

This means that in-situ slum rehabilitation should facilitate community formation through spatial organisation and land rights. In 2018, the Odisha government launched the Jaga Mission to provide land rights to impoverished families living in urban slums, under which 2.4 lakh families have been covered together with f inancial assistance to construct houses.

In-Situ Slum Resettlement Options

Based on a multiple index system the various options can be developed for the slum resettlement. By a creative, participatory process each slum redevelopment or upgradation scheme can be unique having its own identity. It is possible to upgrade old communities or to design new ones which bring charm and delight to informal settlements with winding lanes, shady places to gather and sit, places for markets, temples, playgrounds, etc. Each individual plan addresses the specific local issues and provides following choices:

a. In-situ upgrading

b. Relocation

c. Land sharing

d. Reconstruction

e. Re-blocking.

In situ upgrading and regularisation should be the priority. The relocation can be in the form of Site and Services. Land sharing is suitable for old//illegal slum clusters/ buildings like chawls. Reconstruction can be taken up in the slums with very deficient services and degraded, dangerous structures, as adopted in Mumbai, Japan, and elsewhere. (Fig. 12).

The participatory local planning aims at integration of slums with city development plan, social welfare, organisational development, and income generation, with linkages between the markets and informal sector. Micro financing and small loans can be of immense help to empower and enable the poor to integrate themselves with the network of transactions in the urban system. A working committee networks local communities with the local authority, service agencies and the NGOs. The architects, planners and engineers can act as the catalysts in facilitating planning and development as a collective and collaborative process, which cover the following plans:

• Infrastructure development plans: lanes and roads, water supply and electricity, storm and sewage drains, solid waste disposal, renewable energy, rainwater harvesting, etc. at household and community levels.

• Environmental development: Climate and disaster resilience, heat mitigation plan, plans may include tree planting and greenery, community gardening, waste-water and trash recycling, renewable energy, playgrounds, recreational areas, etc.

• Social development plans: Schools, coaching centres, security posts, public toilets, CCTV, ICCC, vocational training, welfare centre, creche, youth and day-care centre, clinics, hostels and night shelter, universal access, community centres, multi facility centres, communication system, fire-fighting facilities, etc.,

• Economic development: Project f inancing plans, developing vendor/ open markets, kiosks, stores, mixed land use, conservation or heritage tourism areas, community enterprises, loans for small businesses, support for household workshops and vocational training.

MPD 2021 provides upto 40% of land/FAR for market sale to make slum rehabilitation self-financing and viable. A community based collective slum resettlement involves transformation and innovation in the layout planning and spatial organisation. Its success depends upon the active involvement of people and community formation. Various options have been developed by the architect Christopher Benninger who worked on World Bank assisted Site and Services Projects in Chennai and other cities (Figs. 13 and 14).

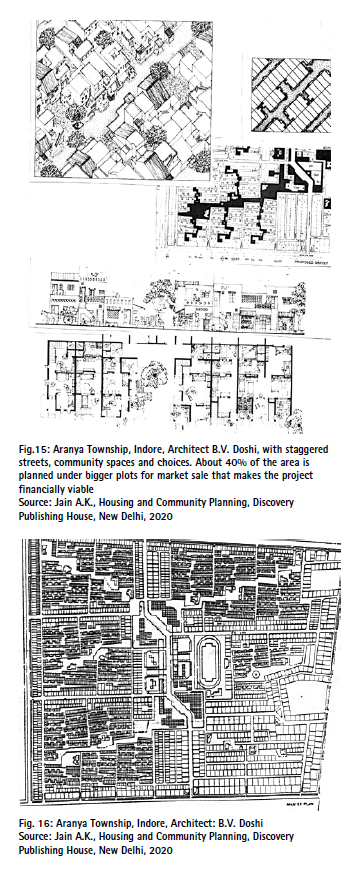

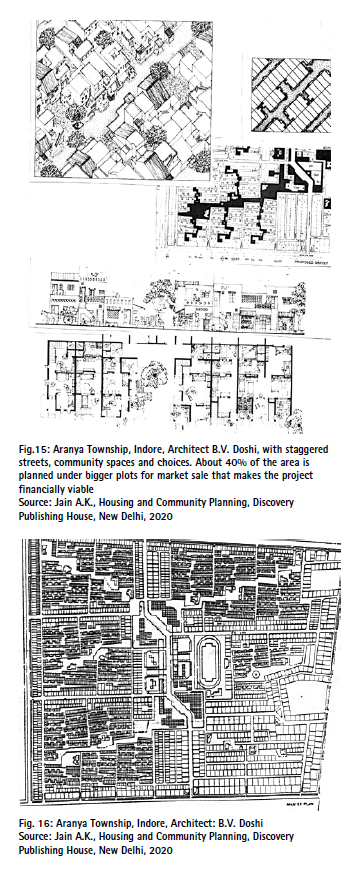

It should be borne in mind that not all slum dwellers are keen to have or need subsidised housing. Many of such families can afford to pay the full price for their plot/dwelling, if it meets their aspirations. In the Aranya township at Indore, B V Doshi provided a combination of subsidised resettlement plots along with non subsidised bigger size plots and incremental housing clusters. The service cores for a group of plots facilitate community living and provide self-employment opportunities to the women (Figs. 15 and 16).

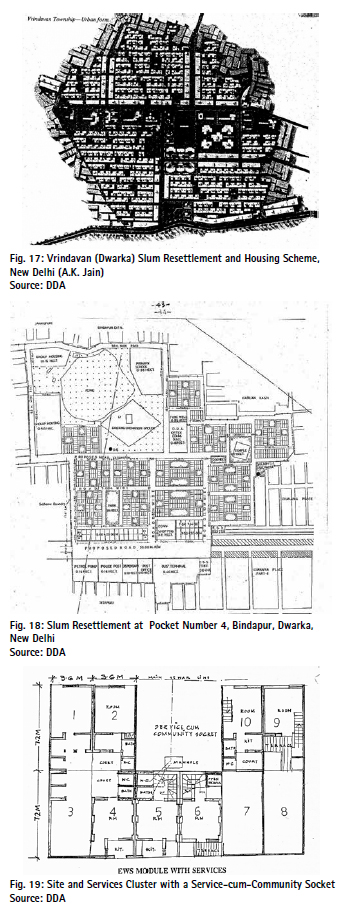

The resettlement schemes taken up in Dwarka Sub-city in New Delhi were based on a cluster of 10 resettlement plots with a service-cum-community socket (6m x7m) where the households, particularly women could assemble, live and work together (Figs 17 to 20). To help self-employment, mixed land use plots with a shop on ground f loor were provided along the main roads.

For most of the slum dwellers, livelihood is a major issue. As such, it was made mandatory that 10% of the space in all shopping centres is reserved for street vendors and informal traders, in the form of vending stalls, kiosks and platforms. Electric handcarts for fruits and vegetable vendors have been redesigned with a non-electric cold storage

Support-Infill In Situ Resettlement:

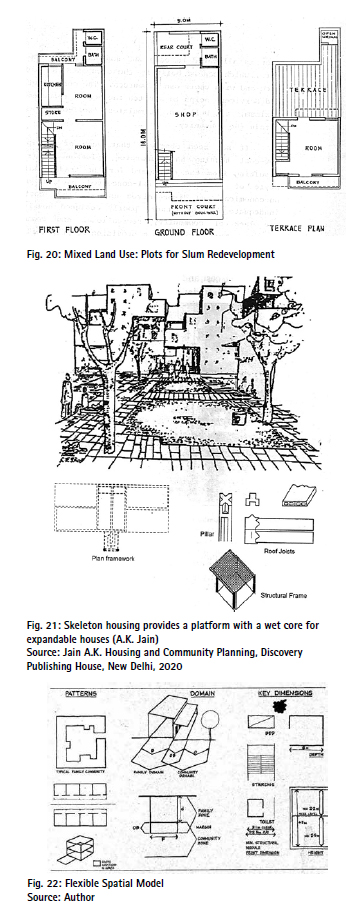

The ‘Support-Infill’ process is based on the 3-dimensional skeletal grid, designed on a modular basis and utilising simple precast components, which permits large variations, adjustments, negotiations and extensions of the dwellings. The skeletal system does not require sophisticated machinery, plant and skills for its production and assembly. The conceptual framework of ‘supports based housing’, is based on a detailed analysis and identification of the actors, domains, morphological and spatial relationships and components of housing development. The space modules are developed for variety of dwelling unit design which allow several permutations and combinations based on concept of domain and right of transformation the concept of differentiated responsibilities. The skeletal structure can either be erected by the people themselves or by a centralised organisation (Figs. 21 to 23).

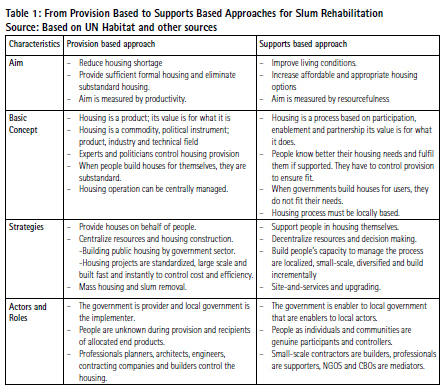

In contrast to provision-based housing and resettlement supports-based slum rehabilitation is based on participatory and evolutionary processes (Table 1).

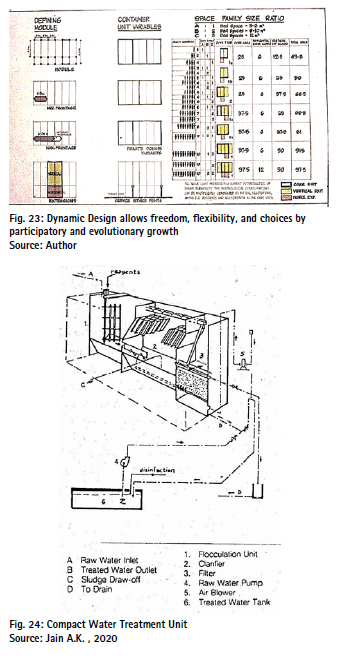

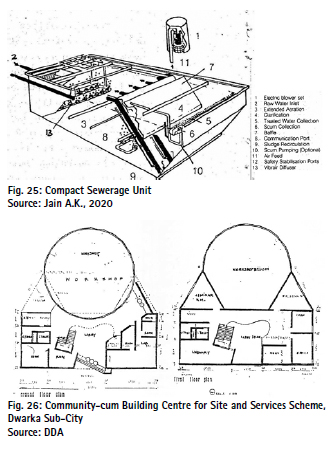

As the city services are not immediately available in the slums and resettlement schemes, the alternative, packaged and self-contained units, such as Compact Water Treatment unit (Fig. 24), Compact Sewerage Unit (Fig. 25) and a Tunnel Reactor for solid waste treatment can be provided. To facilitate skill development a Building Centre can be a useful aid in self -building as it was proposed in Dwarka Sub-city (Fig. 26). A Community- Hall cum-Building Centre may be provided for every 1500 to 2500 plots.

Conclusions

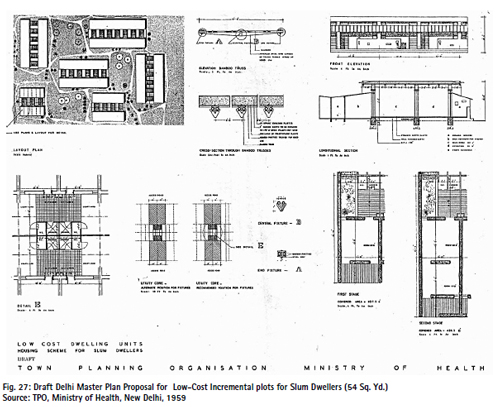

In situ Slum Rehabilitation as stipulated in the Delhi Master Plan 2021 needs a review with respect to its high density high-rise resettlement pattern. I recall the incremental plots for slum dwellers proposed in the Draft Master Plan for Delhi (1959), which was a reduced version of Rehabilitation Colonies for Refugees (Fig. 27).

This can still be an option for slum rehabilitation in the Delhi many slum dwellers would prefer them rather than multi storied flats of 25 sq. m. The mandatory norm of 15 percent of FAR for EWS/LIG/Slum housing can supplement the slum rehabilitation efforts in various housing projects.

The Delhi Chief Minister on 2nd August 2025 had announced developing 10 lakh houses for the poor. This requires about 5,000 Ha net land or 10,000 Ha gross for which there is no option but to go beyond the NC Terrirtory of Delhi, and explore the areas in the DMA, preferably along the Mass Transit Corridors.

In-Situ Slum Rehabilitation also covers the options of upgradation, relocation, land sharing, reconstruction and reblocking. As compared to provider’s model, it is longitudinal and community led, where the community plans and implements. This involves surveying and mapping and preparing slum resettlement plans, together with resolving the tenure and infrastructure issues.

The strategy of using the strength of the communities should be the starting point in the process of in-situ rehabilitation. “Demand-driven” rather than “supply driven” approach allows the communities to plan and implement the projects themselves.

A radical change is that the money is controlled by the communities, who decide how to use subsidies, land, building resources and managing their construction. This means adopting support-based approach led by local community who plan and decide together. An important aspect of the program is to provide professional guidance to the communities by the NGOs, architects, institutions or engineers. In this way a new partnership between communities, local governments and other organisations can be established, integrating social, environmental and economic well being of the local communities. The support-based resettlement promotes variations rather than standard solutions. In a competitive world of private sector buying out the prime areas occupied by the poor, it is necessary to review the processes of PPP, EPC and L-1 in slum rehabilitation. These have lead to verticalization and commodification of social housing, which hardly benefits the poor slum dwellers.

In the alternative model, it is the communities who take decisions and implement, whereas the government takes the role of facilitator and supporter. Secure land tenure is the foundation of slum rehabilitation. The communities can negotiate their own tenure arrangements through strategies such as cooperative land purchase, long-term lease contracts, land-swapping or user rights. The emphasis is on obtaining collective, rather than individual land tenure.

References

ADB and CRISIl, Strategic Framework for a Slum Free Delhi, DUSIB, GNCTD, New Delhi, 2013

Ali, Sabir, Environment and Resettlement Colonies of Delhi, Har Anand Publications, New Delhi, 1995

BMTPC, PMAY (U) and Light House Projects, Nirman Sarika, 2022

Chakravarty, Sanjay and Netranjan Sarkar, Colossus – The Anatomy of Delhi, Cambridge University, New Delhi, 2011 Christopher Benninger, Architecture for Modern India, India House, Pune, 2015

Delhi Development Authority, Master Plans for Delhi, DDA, New Delhi, 1962, 2001 and 2021

Dupont, Veronique, Emma Tarlo, Denis Vidal Delhi Urban Space and Human Destinies, Manohar, New Delhi, 2000

Gupta R.G., Shelter for the Poor in Fourth World, Vols. 1 &II, Shipra, New Delhi, 1995

Jagmohan, Island of Truth, New Delhi: Vikas Publishing House, 1978.

Jain A.K. Empowering the Poor by Slum and Squatter Resettlement in Delhi, Coordinates, November 2024

Jain A.K., Low-Income Settlement Design, Bindapur, Dwarka, New Delhi, Delhi Vikas Varta, July/Sept. 1990

Jain A.K. The Informal City, Readworthy, New Delhi, 2011 Jain A.K., Housing Design- An Alternative Model, Delhi Vikas Varta, 1983

Jain A.K., Housing Development Technique, Open House, Vol. 8, No. 11, 1983

Jain A.K., Community and Social Interaction, Built Environment, June 1973

Jain A.K. Building Systems for Low Income Housing, J.M. Jaina, New Delhi, 2006

Jain, A.K., Transforming Delhi, Bookwell, New Delhi, 2015

Jain A.K., Housing and Community Planning, Discovery Publishing House, New Delhi, 2020

Jain A.K., The Informal Settlements (Unpublished) IHS/BIE, Rotterdam, 1980

Jain A.K., Community and Social Interaction, Built Environment, June 1973

Kulkarni, Dhaval, The Big Adani Gamble Can the Tycoon Transform Asia’s Largest Slum? India Today, August 4, 2025

Ministry of Urban Development, Report of the Committee on Making Delhi Slum Free, 2004

Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs, Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (Urban), 2015, 2023

Mishra, Girish and R.K., Sharma, Resettlement Policy of Delhi, IIPA, New Delhi, 1981

Patwari S, Bo Tang and Maurice Mitchell (eds.) Learning from Delhi- Dispersed Initiatives in Urban Landscape, Ashgate, Surrey, 2010

Payne, Geoffrey, Urban Housing in the Third World, TBS, London, 1977

Slum Improvement in the National Capital Territory of Delhi, GNCTD, 1999

Riberio, E.F.N, Shelter Types and Possible Approaches, AMDA, New Delhi, 2000

Royal College of Fine Arts and Architecture, Dharavi, Documenting, Informalities, Academic Foundation, New Delhi, 2009

Stichting Architecten Research (SAR) Eindhoven, Levels and Tools, 1979

Times of India, No Demolition Without Pucca Houses, CM, 2nd August 2025

Times of India, Government to Draft Plan to Provide 10 Lakh Houses for City’s Poor, 3rd August 2025

Town Planning Organisation, Draft Master Plan for Delhi, Government of India, 1959

Turner, John, Housing by People: Towards an Autonomy in Building, Mariam Boyers, London, 1976

UN Habitat, The Challenges of Slums, Earthscan, London, 2003

UN Habitat, The New Urban Agenda, Nairobi, Kenya, 2015.

World Bank, Reconsidering Site and Services The World Bank, Washington, 2022.

(2 votes, average: 1.00 out of 5)

(2 votes, average: 1.00 out of 5)

Leave your response!