| Perspective | |

Humorous science: An introduction

As the world continuous to struggle with the COVID-19 pandemic, this paper provides an introduction to the use of humour in the scientific literature and highlights several examples |

|

|

This is the first in a series of papers celebrating some of the weird and wonderful research findings hidden amongst the scientific literature. It aims to ensure that we remember the funnier side of science and provides answers to questions we may have been too afraid to ask. This study was conducted entirely in the author’s spare time and is in no way related to his employer. To get started, we explore some general issues about publishing research and the difficulties associated with it.

Humorous papers can improve student learning and have the potential to convey scientific information to a much wider and much more general and diverse audience. Often, they have a more serious message that is hidden between the lines or disguised by tackling a ridiculous topic. In an age of increasing importance of high-quality, peer-reviewed research output by academics (‘publish or perish’), it would be a shame to lose the funny side of science as it is also a crucial part of academic freedom. Thankfully, some journals continue to support the publication of the occasional humorous paper, sometimes with unexpected results. For example, several years ago, a study on the indirect tracking of drop bears using Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) technology was published in the Australian Geographer (Janssen, 2012) and quickly became the most downloaded paper in the journal’s online history.

To honour unusual and imaginative research, the science humour magazine Annals of Improbable Research introduced the Ig Nobel Prizes in 1991. The aim is to make people laugh and then think, and along the way spur their interest in the various sciences. The prizes are presented to the winners by genuine Nobel laureates during an annual gala ceremony held at Harvard University. Indeed, several of the studies mentioned in this series of papers on humorous science received the Ig Nobel Prize.

The Journal of Irreproducible Results, founded in 1955, is another science humour magazine worth mentioning. These magazines often include shorter communications addressing intriguing research questions such as: Which came first, the chicken or the egg? Does it rain more often on weekends? Can you compare apples and oranges? How do cats react to bearded men? Is an eye for an eye worth more than an arm and a leg? What is the dead-grandmother exam syndrome?

To set the reader’s mind at ease, here are brief answers to these questions: The chicken came first, proven experimentally using a chicken, an egg and the US Postal Service (but conflicting with a later theoretical answer collaboratively provided by a geneticist, philosopher and chicken farmer). Yes, certain locations exhibit more rain on weekends than weekdays (and vice versa), proven by analysing precipitation data from nearly 200 stations across the US over 40 years. Apples and oranges can indeed be compared and are actually very similar, proven experimentally via infrared spectra of apple and orange extracts, and later confirmed by Barone (2000) who identified a significant difference only in the categories of colour and seeds. Female cats dislike men with long dark beards, proven by analysing the reactions of 214 cats to photographs of bearded men, measuring changes in pulse rate, respiration, eye dilation, fur shed rate and qualitative behaviour. An arm and a leg are worth less than two eyes, proven by determining the psychological worth people attribute to various parts of the human body.

The dead-grandmother exam syndrome implies that a student’s grandmother is far more likely to die suddenly just before the student takes an exam than at any other time of year (particularly if the student’s current grade is poor), proven based on 20 years of data collected and analysed by Adams (1999). A student who is about to fail a class and has a final exam coming up was found to be more than 50 times more likely to lose a family member than an excellent student not facing any exams. This clearly showed that family members literally worry themselves to death over the outcome of their relatives’ exam performance.

Another valuable source of science humour is arXiv (https://arxiv.org/), a free open-access archive for scholarly articles in various fields of science, many of these denoted as submitted or in print. Materials on this site are not peer-reviewed by arXiv and include contributions that may never have been intended for submission elsewhere or had their titles de-humorised for publication. An intriguingly large number of papers are uploaded to this archive around April Fool’s Day each year.

Getting published

Starting with the difficulty to write an academic paper, Upper (1974) famously reported on the unsuccessful selftreatment of a case of writer’s block (Figure 1). The reviewer mentioned at the time: “I have studied this manuscript very carefully with lemon juice and X-rays and have not detected a single flaw in either design or writing style. I suggest it be published without revision. Clearly it is the most concise manuscript I have ever seen – yet it contains sufficient detail to allow other investigators to replicate Dr Upper’s failure.” Decades later, this indeed spawned a multi-site crosscultural replication of the study, showing a remarkable agreement of results between the two (Didden et al., 2007).

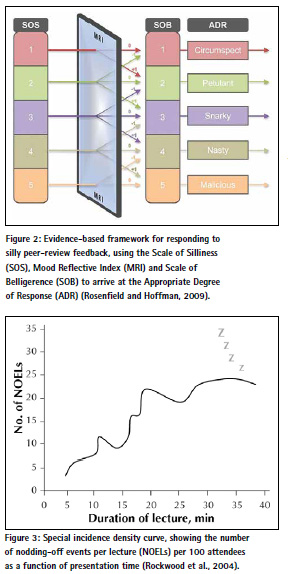

The feedback received from reviewers during the rigorous peer-review process is usually constructive and helpful in improving the submitted paper, but sometimes it can be incomprehensible or plain silly. In order to help emerging academics to appropriately navigate the peer-review process in these cases, Rosenfield and Hoffman (2009) developed an innovative, evidencebased framework for providing “snappy answers to stupid questions”. The received (inadequate) feedback is given a score on the five-tiered Scale of Silliness (SOS), which can be adjusted by ±1 through the Mood Reflective Index (MRI) depending on the author’s personal disposition at the time, to obtain the Scale of Belligerence (SOB), which determines the Appropriate Degree of Response (ADR). The ADR ranges from timid circumspection (caution) all the way to extreme maliciousness, with mild petulance, moderate snarkiness and severe nastiness in between (Figure 2).

It was noted that applying this framework to its full extent may have negative consequences, such as loss of promotion or research funding, but its therapeutic value cannot be understated. Also, it should only be used in conjunction with high-quality submissions that reviewers either did not understand or did not give sufficient attention to, as poorly written and under-researched submissions probably deserve the feedback received. In a quest to provide recommendations for writing good paper titles, Subotic and Mukherjee (2014) investigated title characteristics (length, type, amusement and pleasantness) and title markers (colons and attention-grabbing words) in relation to subsequent paper downloads and citations in the field of psychology. Examples of titles classified as highly amusing included ‘How extraverted is honey.bunny77@hotmail.de? Inferring personality from e-mail addresses’ and ‘Taking a new look at looking at nothing’.

They determined that title length and title amusement (humour) were the most important characteristics, with shorter titles being associated with more citations. However, it was noted that this result may be an artefact caused by the naturally higher citation rate of higher-impact journals. Papers with more humorous titles showed slightly more downloads but were not correlated with citations, and more amusing titles tended to be shorter. Noting that more research is required to understand how relevant title characteristics relate to each other, they recommended to keep the title short and amusing, within common sense and good taste, and that colon usage probably does not matter.

Research findings are often presented at conferences and seminars. Rockwood et al. (2004) explored how often attendees nod off during scientific meetings and examined risk factors for this behaviour. After counting the number of heads falling forward during a 2-day lecture series attended by 120 people (this method was chosen because counting is scientific), they calculated incidence density curves for nodding-off events per lecture (NOELs) and assessed risk factors using logistic regression analysis. The quality of the lectures varied from entertaining and informative to monotonous and repetitive, to rushed and surreal. The incidence density curve ranged from 3 to 24 NOELs, with a median of 16 NOELs per 100 attendees (Figure 3).

Identified risk factors for nodding off included environmental factors (dim lighting, warm room temperature, comfortable seating), audio-visual factors (poor slides, failure to speak into the microphone) and circadian factors (early morning, post meal), but speaker-related behaviour (monotonous tone, tweed jacket, getting lost in the lecture) provided the strongest risk. A questionnaire administered to those who nodded off revealed that most were comforted to know they were not alone and that it was predominantly the speaker’s fault. Most had no enthusiasm to attend boring presentations but were influenced by continuing professional development (CPD) credits, guilt or obsessiveness.

Since this paper generated considerably more interest than the authors’ more conventional publications, they decided to write a follow-up (Rockwood et al., 2005). Here, they performed a comprehensive, international systematic review of nodding off and napping during medical presentations, spanning more than 100 years (but only three papers during that time, including their own). The results suggested that tranquillising lectures are common, annoying and persistent, with low lighting and boring (and badly presented) contents being the main risk factors for nodding off. The authors also provided a few tips on how to help increase the attention a paper may receive after publication through ingested keywords, citations and tweaking the methodology to exclude unwanted references.

Humorous publications

Noting that comedy can tell us something important about the human condition, Watson (2015) encouraged the use of humour as a methodology for carrying out research and presenting its findings in the social sciences. She concluded that academics should take seriously their responsibilities as producers of research to entertain and as consumers to read for fun. This is not an easy task, considering the danger of having a humorous paper rejected by the targeted publication or, once published, potentially losing credibility amongst peers and thereby jeopardising one’s professional career. Focussing on the field of physics and astronomy, Scott (2021) reiterated the need to see the funny side of science, while taking the reader through history and many entertaining examples. In a world still suffering from the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, maybe this is now more important than ever.

However, it should be noted that opposing views on humour exist. For example, Bentall (1992) proposed classifying happiness as a psychiatric disorder, arguing that it is statistically abnormal, consists of a discrete cluster of symptoms, reflects the abnormal functioning of the central nervous system and is associated with various cognitive abnormalities (in particular, a lack of contact with reality). He suggested to replace the ordinary language term ‘happiness’ with the more formal description ‘major affective disorder, pleasant type’ in the interest of scientific precision and the hope of reducing any possible diagnostic ambiguities. He concluded that once the debilitating consequences of happiness become widely recognised, it is likely that psychiatrists will begin to devise treatments for the condition, soon leading to the emergence of happiness clinics and anti-happiness medications.

Fortunately, over the years, researchers in many areas of science have taken on the challenge of being entertaining. While often hidden among more serious research results, fruits of these endeavours have been compiled in several lists of funny papers, generally focussing on a particular discipline (e.g. Martin, 2001; McCrory, 2006; Scott, 2021).

Here are only a few examples of papers included on these lists:

•Audoly B. and Neukirch S. (2005) Fragmentation of rods by cascading cracks: Why spaghetti does not break in half, Physical Review Letters, 95(9), 095505.

• Barss P. (1984) Injuries due to falling coconuts, Journal of Trauma, 24(11), 990-991.

• Bowman R. and Sutherland N.S. (1969) Discrimination of ‘W’ and ‘V’ shapes by goldfish, Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 21(1), 69-76.

• Forrest J.B. and Gillenwater J.Y. (1982) The hand vacuum cleaner: Friend or foe? Journal of Urology, 128(4), 829.

• Georget D.M.R., Parker R. and Smith A.C. (1994) A study of the effects of water content on the compaction behaviour of breakfast cereal flakes, Powder Technology, 81(2), 189-195.

• Hatta T. and Kawakami A. (1999) Are nonproper chopstick holders clumsier than proper chopstick holders in their manual movements? Perceptual and Motor Skills, 88(3), 809-818.

• Sidoli M. (1996) Farting as a defence against unspeakable dread, Journal of Analytical Psychology, 41(2), 165-178.

• Sreekumar K.P. and Nirmalan G. (1990) Estimation of the total surface area in Indian elephants (Elephas maximus indicus), Veterinary Research Communications, 14(1), 5-17.

• Verhulst J. (1999) Nonuniform distribution of the elliptical longitudes of sun and moon at the birthdays of top scientists, Psychological Reports, 85(1), 35-40.

• Ward W.D. and Holmberg C.J. (1969) Effects of high-speed drill noise and gunfire on dentists’ hearing, Journal of the American Dental Association, 79(6), 1383-1387.

Other amusing papers include Blackler et al. (2016) confirming that users of various products and interfaces generally find life is too short to RTFM (read the fricking manual), which may be of particular concern to spatial professionals regularly employing sophisticated equipment. Using a series of questionnaires administered to 170 people over 7 years and two 6-month studies based on diaries and interviews with a total of 15 participants, they found that most people do not read the documentation and do not use all features of the products they own and utilise regularly. Men are more likely to do both than women, younger people are less likely to use manuals than middleaged and older ones, and more educated people are also less likely to read manuals. Furthermore, it appears that over-featuring and being forced to consult manuals causes negative emotional reactions in users. The findings therefore suggest that people do not read manuals because they find it a negative experience, overly complicated and feel that the interface itself should tell them all they need to know.

The application of human saliva to clean dirty surfaces has been an intuitive practice for many generations (and caused many children to protest in disgust when their parents used this technique on them). Apparently, conservators have been cleaning old paintings and statues with their own spit for years because they discovered that it can clean an artefact without breaking it down. Romao et al. (1990) finally established the scientific basis for this practice, performing tests on five gilded and polychromed sculptures dating from the 18th century and applying chromatographic techniques to separate and investigate the components of saliva. Compared to other cleaning agents tested, saliva was confirmed as the best cleaner. However, it was noted that it slightly attacked red and blue matte surfaces.

Blinder (1974) presented a new model for brushing teeth, arguing that the existing bad-taste-in-your-mouth and mothertold-me-so models were not sufficiently rigorous to describe this phenomenon. Applying an assumption common to all human capital theory (individuals seek to maximise their income), his model is firmly grounded in economic theory and considered the toothbrushing decisions of chefs and waiters working in the same restaurant. On the benefits side, chefs are rarely seen by customers and work on a consistent salary. Waiters, on the other hand, constantly interact with the public and rely on tips for most of their income, i.e. bad breath and/or yellow teeth could have damaging effects on their earnings. On the cost side, since wages for chefs are higher, the opportunity cost of brushing is correspondingly higher. Therefore, the theory predicts that chefs brush their teeth less often than waiters.

The model predictions were empirically confirmed through the analysis of data obtained from a cross-sectional study of American adults in the civilian labour force, conducted by the Federal Brushing Institute (FBI), which included denture wearers but excluded people with no teeth at all. Thus, the study demonstrated the usefulness of human capital concepts in understanding dental hygiene. Furthermore, it was noted that the model could also be applied to other problems such as combing hair, washing hands or cutting fingernails.

Staying with economics, McAfee (1983) applied counterfactual analysis to examine American economic growth if Columbus had fallen off the edge of the world rather than stumbled across the American continents. He constructed a theoretical model of the Earth in which implications of Columbus falling off the edge could be tested and used a novel analytical procedure (Fractured Reconstructive Autoerotic Projection Package with Econometrisation, FRAPPE) to detail the properties of the counterfactual world.

This revealed that the US would be relatively unchanged and therefore unaffected by tinkering with history. However, the rest of the world would be drastically different, which was illustrated by presenting a rough chronology of events following Columbus’ demise. For example, in a daring exploit, Australia was unfastened from the Pacific rim by a team of Welsh divers and sneaked past India and Africa to be fastened near the edge of the world about 1,000 miles off Britain. While travelling around the Cape, Australia was accidently inverted, causing this new continent of America to look remarkably like today’s US. It was first used as a penal colony for former British Lords and French royalty who eventually revolted, and the rest is history. It was also speculated that if the Earth had more than one moon, the space race would have turned out differently, representing an m nation n moon problem.

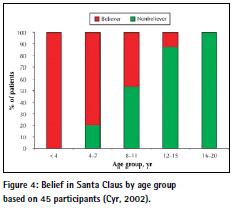

Cyr (2002) investigated the level of belief in Santa Claus among 45 inpatients at a children’s hospital. The answers obtained during a structured interview, which also included questions about the Tooth Fairy and Easter bunny, along with separate questions for parents were combined into a final score (HOHO score) of family fantasy predisposition. Statistical analysis demonstrated that belief in Santa Claus was inversely proportional to a child’s age and directly proportional to the age at which their parents stopped believing. In other words, as expected, belief in Santa diminished with increasing age (Figure 4). It was noted that a multivariate analysis failed to relate the HOHO score to belief in Santa, which may be due to the HOHO score reflecting an assimilation of cultural folklore rather than independent fantasy predisposition.

Finally, it is known that only female vinegar flies produce a particular pheromone for communication and mate-finding. A pheromone is basically a hormone working outside the body, i.e. a chemical produced by an animal that changes the behaviour of another animal of the same species (perhaps comparable to a human wearing perfume). Becher et al. (2018) discovered that they could distinguish male from female flies just by sniffing them, so they devised a series of experiments to investigate whether a panel of eight wine connoisseurs could do the same. This included asking panel members to smell empty wine tasting glasses, which had previously contained a male or female fly for 5 minutes. Then, a female fly was added to a glass of water or wine (and removed before testing), and additional tests were conducted using a synthetic chemical corresponding to the female fly scent. Statistical data analysis revealed that the scent of a single female fly was stronger and qualitatively clearly different from a male fly and that even a small amount of the female fly scent was perceptible, spoiling a glass of wine.

Conclusion

This paper has only been able to provide a brief introduction into the fascinating world of amusing research, which generally applies serious science to weird and wonderful research questions but also includes the occasional spoof paper. Upcoming papers in this series on humorous science will highlight selected examples of entertaining research for particular areas of interest, often including a considerable spatial component. This includes typical problems encountered in the workplace office environment, analysing the coexistence of humans and vampires or zombies, animal mapping and behaviour, grappling with applied physics in our everyday lives, as well as studies related to work health and safety and our physical and mental wellbeing.

References

Adams M. (1999) The dead grandmother/exam syndrome, Annals of Improbable Research, 5(6), 3-6.

Barone J.E. (2000) Comparing apples and oranges: A randomised prospective study, BMJ, 321(7276), 1569-1570.

Becher P.G., Lebreton S., Wallin E.A., Hedenström E., Borrero F., Bengtsson M., Joerger V. and Witzgall P. (2018) The scent of the fly, Journal of Chemical Ecology, 44(5), 431-435.

Bentall R.P. (1992) A proposal to classify happiness as a psychiatric disorder, Journal of Medical Ethics, 18(2), 94-98.

Blackler A.L., Gomez R., Popovic V. and Thompson M.H. (2016) Life is too short to RTFM: How users relate to documentation and excess features in consumer products, Interacting with Computers, 28(1), 27-46.

Blinder A.S. (1974) The economics of brushing teeth, Journal of Political Economy, 82(4), 887-891.

Cyr C. (2002) Do reindeer and children know something that we don’t? Pediatric inpatients’ belief in Santa Claus, CMAJ, 167(12), 1325-1327.

Didden R., Sigafoos J., O’Reilly M.F., Lancioni G.E. and Sturmey P. (2007) A multisite cross-cultural replication of Upper’s (1974) unsuccessful selftreatment of writer’s block, Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 40(4), 773.

Janssen V. (2012) Indirect tracking of drop bears using GNSS technology, Australian Geographer, 43(4), 445-452.

Martin N. (2001) Weird and wonderful, The Psychologist, 14(9), 484-485.

McAfee R.P. (1983) American economic growth and the voyage of Columbus, American Economic Review, 73(4), 735-740.

McCrory P. (2006) Who says you cannot get published? British Journal of Sports Medicine, 40(2), 95.

Rockwood K., Hogan D.B. and Patterson C.J. (2004) Incidence of and risk factors for nodding off at scientific sessions, CMAJ, 171(12), 1443-1445.

Rockwood K., Patterson C.J. and Hogan D.B. (2005) Nodding and napping in medical lectures: An instructive systematic review, CMAJ, 173(12), 1502-1503.

Romao P.M.S., Alarcao A.M. and Viana C.A.N. (1990) Human saliva as a cleaning agent for dirty surfaces, Studies in Conservation, 35(3), 153-155.

Rosenfield D. and Hoffman S.J. (2009) Snappy answers to stupid questions: An evidence-based framework for responding to peer-review feedback, CMAJ, 181(12), E301-E305.

Scott D. (2021) Science spoofs, physics pranks and astronomical antics, https://arxiv. org/abs/2103.17057 (accessed Aug 2021).

Subotic S. and Mukherjee B. (2014) Short and amusing: The relationship between title characteristics, downloads, and citations in psychology articles, Journal of Information Science, 40(1), 115-124.

Upper D. (1974) The unsuccessful self-treatment of a case of “writer’s block”, Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 7(3), 497.

Watson C. (2015) A sociologist walks into a bar (and other academic challenges): Towards a methodology of humour, Sociology, 49(3), 407-421.

(2 votes, average: 4.00 out of 5)

(2 votes, average: 4.00 out of 5)

Leave your response!