| GIS | |

How one million people in India’s Odisha slums gain land rights

The Tata Trusts began the effort with pilot studies that gained momentum with the historic passage of the Odisha Land Rights to Slum Dwellers Act in August 2017 |

|

|

In India, having patta or property title, forms the basis for social and financial opportunity. It often provides the only acceptable proof of address required to access government benefits, enroll children in school, and open a bank account. An ambitious program in India’s state of Odisha has begun to deliver land rights to people living in slums.

“This project was conceived from the realization that slum dwellers are the lifeline of the city and our state can’t be developed without uplifting them,” said G. Mathi Vathanan, commissioner-cum-secretary, Housing and Urban Development Department, Government of Odisha. The Tata Trusts began the effort with pilot studies that gained momentum with the historic passage of the Odisha Land Rights to Slum Dwellers Act in August 2017. The legislation puts a program in motion to identify, map, and issue title for parcels of land in 2,000 slums that house a population of 1 million people. “This landmark legislation is going to change the face of slums across the country,” said R. Venkataramanan, managing trustee, the Tata Trusts. “Hopefully, this effort in the slums of Odisha will have a ripple effect across the country with a positive social and economic impact.”

“This is an incredibly exciting program,” said Frank Pichel, chief programs officer at Cadasta Foundation, a nonprofit that provides technical tools and services to support the efficient documentation of land rights globally. “This first-of-itskind program has shown the potential of bottom-up data documentation leading to formal certificates of occupancy in urban informal communities.”

The legislation promises a Certificate of Occupancy of 30 square meters (roughly 320 square feet) free of cost to the economically disadvantaged, as well as financial assistance of up to 200,000 rupees ($2,900) that the homeowner can use to create a permanent dwelling. Odisha’s effort is part of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s larger Housing for All Mission that aims to build 20 million urban housing units and 30 million rural homes by 2022.

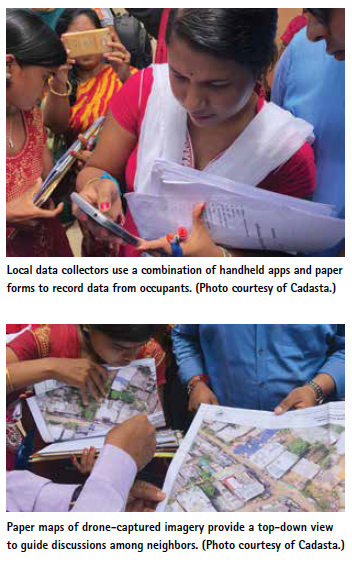

Local data collectors use a combination of handheld apps and paper forms to record data from occupants. (Photo courtesy of Cadasta.)

Getting the record right

Around the world, 70 percent of the population live on land without holding title. Peruvian economist Hernando de Soto helped raise awareness about the impact of granting land title by writing several best-selling books. He argues that guaranteeing urban property rights is a precondition for alleviating poverty.

Many governments have experimented with de Soto’s ideas and the World Bank has loaned funds to support related projects, however, the complexities of land reform have yielded several false starts.

According to Transparency International, the land sector is the third most corrupt government sector globally behind police and judiciary.

“A lot of places where we’ve worked, the slums are owned by the politically or economically powerful,” Pichel said. “They are happy for it to remain informal, because they can control it and continue charging unreasonable rents knowing they can always evict a person if they don’t pay.”

Even where land records exist, historical information can be inaccurate or not up-to-date. Often, when reforming land records, it’s cheaper and easier to inventory existing occupancy rather than correct old records.

“In other countries we’ve seen deed books with blank or torn out pages,” Pichel said. “A torn-out page means someone’s deed disappeared. A blank page means the official can predate a deed to give favor to the person that pays them the most.” Streamlined digital workflows have started to reverse these issues.

“Technology brings in ease of doing this accurately, transparency in the process, removes discrepancies, reduces the dependency on human interventions, and brings in speed in execution,” Vathanan said. “It also helped avoid large-scale disputes, litigation, and discontentment that would have resulted in frustration and failure.”

Paper maps of drone-captured imagery provide a top-down view to guide discussions among neighbors. (Photo courtesy of Cadasta.)

Efficient workflows

The government’s partner, the Tata Trusts, brought in global best practices by mobilizing partners like Norman Foster Foundation, Omidyar Network, and Cadasta. The government also partnered with more than 27 local civil society organizations for data collection and validation.

They started data collection by using drones to capture high-resolution imagery of the slum areas. This imagery formed a backdrop within the geographic information system (GIS) for drawing boundaries and assigning a plot number. Next, data collectors went door to door using a mobile application to collect survey information from each household. “We brought in state-of-the-art technology and expertise to complete the task in the most efficient manner,” said Shishir Ranjan Dash, who leads the project for the Tata Trusts.

Each step of the way, the teams relied on Esri technology, tailored by Cadasta for the purpose of capturing land information. Workflows include handheld applications configured for the survey task, a claim review process, steps to transfer the formalized land records to the government, and the delivery of four formal certificates of occupancy to the occupants.

Using GIS apps, the field teams, made up of one field manager and five data collectors per neighborhood, achieved a steady pace of capturing records for 200- 250 households per day. This fast pace is important given the extent of the task. The data collectors are local slum dwellers, who capitalize on their local knowledge to speed the work and ensure its legitimacy.

Smartphones are central to the process. Field crews use phones for all steps and the popular texting application WhatsApp is used to communicate progress.

“The number of people in emerging economies interacting with GIS via a web browser on their smartphone as opposed to a computer is incredibly high,” Pichel said. “A few years ago, I would get incredibly frustrated by bandwidth constraints, but that’s no longer the case.” “This program was deliberately designed for doorstep delivery of services,” Vathanan said. “We are pleased that land certificates have been distributed without requiring the slum dwellers to visit any government office even once.”

To date, more than 24,000 certificates have been distributed to slum dwellers and an additional 50,000 will be delivered by the end of March 2019.

The community gathers around a computer to review land records that were captured. (Photo courtesy of Cadasta.)

Compounding benefits

In other countries that have implemented land title reform in informal settlements, long-term stability has evaded residents. From Cambodia to the Democratic Republic of the Congo, giving land title in slums close to commercial centers has resulted in quick land sales and a total turnover of people, with the original settlers displaced within a year’s time.

“In the case of Odisha, the property documentation that residents get enables the properties to be inheritable, but nontransferable,” Pichel said. “So, they can’t sell it, but they could leave it to heirs, and it’s mortgageable.”

Studies show that land title helps lift residents out of poverty by erasing the fear of eviction and cultivating safety and dignity. Title to a house turns it into an insurance and savings tool to provide security for owners during old age or bad times.

Occupants sign a form to certify their ownership, which results in a certificate of occupancy. (Photo courtesy of Cadasta.)

“What you often find in slums where there is a risk of eviction is that somebody remains in the house at all times,” Pichel said. “That way, they can move out all the possessions quickly. With someone needing to be there, it means a child’s not going to school or an adult isn’t out earning an income.”

Land title also shifts investments into more permanent structures. Instead of spending money to rebuild every year after monsoon storms hit, the resources can be placed into more permanent structures that withstand wind and rain. “It is important to create a sense of ownership among the people,” said Shikha Srivastava, the Urban Habitat Portfolio lead at the Tata Trusts. “To ensure this, we are upgrading the slums through a participatory decision making process where the community shares their development vision.”

The State of Odisha’s investment in slums includes roads, drainage, fresh water supply, toilets and sewers, street lights, common work sheds, parks and playgrounds. This expanded vision of the program goes beyond the original promise of land title and includes the transformation of slums into livable habitat.

The article first appeared at https:// www.esri.com/about/newsroom/blog/ how-one-million-people-in-indiasodisha- slums-gain-land-rights.

(5 votes, average: 1.00 out of 5)

(5 votes, average: 1.00 out of 5)

Leave your response!