| GNSS | |

GNSS Constellation Specific Monthly Analysis Summary: October 2025

The analysis performed in this report is solely his work and own opinion. State Program: U.S.A (G); EU (E); China (C) “Only MEO- SECM satellites”; Russia (R); Japan (J); India (I) |

|

|

Introduction

This article continues the monthly This article continues the monthly performance analysis of the GNSS constellation. Readers are encouraged to refer to previous issues for foundational discussions and earlier results. In addition, there is a short overview on the Chi-Square residual RAIM and the associated integrity analysis mechanism. analysis of the GNSS constellation. Readers are encouraged to refer to previous issues for foundational discussions and earlier results. In addition, there is a short overview on the recent anomaly and degradation in the UTC time dissemination parameter from GNSS broadcast messages.

Analyzed Parameters for October 2025

(Dhital et. al, 2024) provides a brief overview of the necessity and applicability of monitoring the satellite clock and orbit parameters.

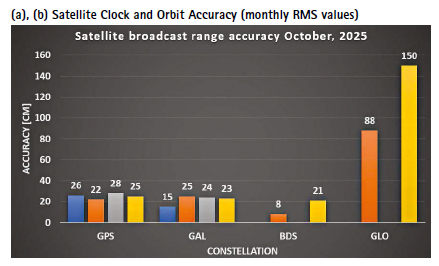

a..Satellite Broadcast Accuracy, measured in terms of Signal-In Space Range Error (SISRE) (Montenbruck et. al, 2010).

b. SISRE-Orbit (only orbit impact on the range error), SISRE (both orbit and clock impact), and SISRE-PPP (as seen by the users of carrier phase signals, where the ambiguities absorb the unmodelled biases related to satellite clock and orbit estimations. Satellite specific clock bias is removed) (Hauschlid et.al, 2020)

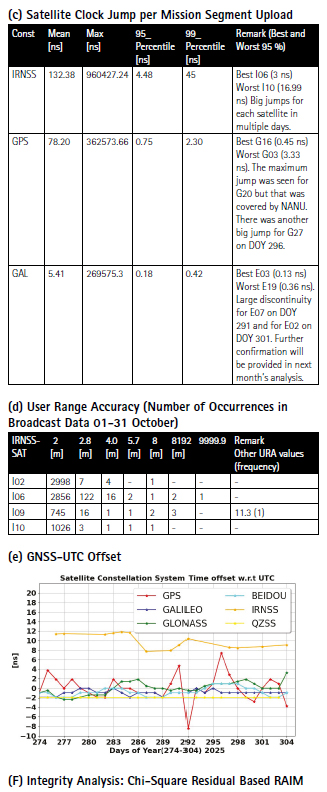

c. Clock Discontinuity: The jump in the satellite clock offset between two consecutive batches of data uploads from the ground mission segment. It is indicative of the quality of the satellite atomic clock and associated clock model.

d. URA: User Range Accuracy as an indicator of the confidence on the accuracy of satellite ephemeris. It is mostly used in the integrity computation of RAIM.

e. GNSS-UTC offset: It shows stability of the timekeeping of each constellation w.r.t the UTC.

f. Chi-Square Residual Based RAIM: It provides a reliable technique for a real time fault detection as well as offline integrity analysis for the system design.

Note:- for India’s IRNSS there are no precise satellite clocks and orbits as they broadcast only 1 frequency which does not allow the dual frequency combination required in precise clock and orbit estimation; as such, only URA and Clock Discontinuity is analyzed.

(F) Integrity Analysis: Chi-Square Residual Based RAIM

Receiver Autonomous Integrity Monitoring (RAIM) is a central concept of GNSS-based aircraft navigation, designed to ensure that position solutions remain trustworthy. RAIM operates in real time by performing two key functions: fault detection and fault exclusion. Detection is achieved through a global consistency check on measurement residuals after computing the least-squares navigation solution. If the residuals indicate inconsistency beyond a predefined threshold, RAIM f lags a fault. Exclusion then isolates the faulty satellite by recomputing solutions with subsets of measurements until consistency is restored. This mechanism allows RAIM to maintain integrity even when a satellite provides erroneous data.

RAIM Detection Logic and Why Chi-Square

The detection test statistic in RAIM is based on the sum of squared residuals:

q² = rᵀr / σ²

where r is the residual vector and σ² is the measurement noise variance. Under the fault-free hypothesis (Hο), the residuals are linear combinations of Gaussian errors, so the sum of their squares follows a Chi-square distribution:

Σ Zᵢ² ~ χ²(df), Zᵢ ~ N(0,1)

This property makes Chi-square the natural choice for RAIM detection. Other distributions, such as Student’s t or F-tests, assume unknown variances or ratio comparisons, which do not apply because RAIM knows the covariance from the measurement model. The detection threshold is:

T² = χ²inv(1 – PFA, df)

If q² > T², RAIM declares a fault. For integrity analysis, fault hypotheses Hᵢ are considered, where the test statistic becomes non-central Chi-square due to bias introduced by faults:

q² ~ χ²(df, λ), λ = ||fault effect on residuals||² / σ²

The residual-based test statistic can also be expressed using the parity vector approach. The parity vector is obtained by projecting measurement errors onto the null space of the geometry matrix H, which isolates inconsistency among measurements. The parity vector p is computed as:

p = (I – H(HᵀH)ˉ¹Hᵀ)z

where z is the measurement vector. The test statistic q² is proportional to the squared norm of the parity vector, making parity RAIM and residual RAIM mathematically equivalent. This formulation is widely used in RAIM literature for fault detection

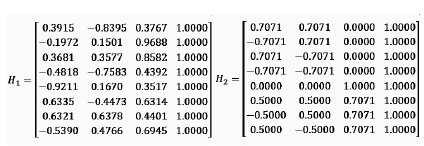

Two example cases are considered here for the demonstration. Geometry matrix H1 representing a satellite to user geometry that is moderately poor and the H2 matrix that is geometrically very good. Based on above mathematical discussions, the fault case analyzed for each satellite and the worst fault satellite is identified along with the total contribution to the probability of the HMI.

Integrity Risk Analysis and Geometry Impact

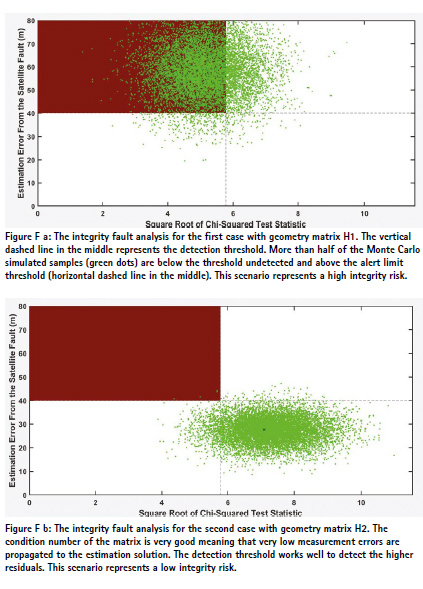

For the first geometry (poor satellite geometry), the analytical bound is P(HMI) = 1.92 × 10-4, with fault-free contribution 1.75 × 10-4 and faulted contribution 1.61 × 10-5. Monte Carlo simulation with 10000 samples (Figure Fa) confirmed that if a fault occurs, the probability of exceeding AL without detection is 74.9%, which is extremely high. The fault analysis plot showed many points in the HMI region, and the worst-case fault produced a large position error (~50 m) but remained undetected because its test statistic was below the threshold. This happens when the fault projects weakly onto the residual space but strongly biases the position estimate—a geometric limitation of residual-based RAIM.

For the second geometry (better satellite distribution), the results improved dramatically: P(HMI) = 1.04 × 10-8, with fault-free contribution negligible (7.0 × 10-14) and faulted contribution 1.04 × 10-8. Monte Carlo simulation gave P(HMI|Hᵢ)P(Hᵢ) ≈ 8 × 10-9, here P(Hᵢ) is prior satellite fault probability of 10-5and with , P(HMI|Hᵢ) ≈ 0.0008—a huge improvement over the previous case. The failure mode plot confirmed this: only few points in the HMI region, and the worst-case fault was detected because its test statistic exceeded the threshold. This demonstrates that satellite geometry strongly influences RAIM performance. A well-conditioned geometry reduces fault sensitivity slopes, improves detection, and lowers integrity risk.

Interpretation of Fault Analysis Plots

Both fault analysis plots (Figure Fa and Fb) visualize the relationship between the square root of the Chi-square test statistic (x-axis) and the position error caused by faults (y-axis). Key elements include

: • Green points: Monte Carlo samples under faulted conditions, showing variability of error and test statistic. Random noise is added to the fault vector (with only the worst-fault satellite having a non-zero value).

• Red shaded region: Hazardously Misleading Information (HMI) zone where position error exceeds the alert limit (AL) while the test statistic remains below the detection threshold.

• Dashed lines: Detection threshold (√T²) and alert limit (AL), defining the safety boundaries.

In the first geometry, many points fall in the HMI region, confirming high integrity risk and missed detections. In the second geometry, points cluster away from the HMI region, and the worst case fault is detected, demonstrating the critical role of satellite geometry in RAIM performance. In this second geometry case, the RAIM can detect the fault and prevents an integrity event.

These results highlight three critical insights: (1) Chi-square RAIM is effective for detecting large residual inconsistencies but cannot guarantee detection of all hazardous faults, especially under poor geometry; (2) Integrity risk analysis of the system is essential because detection alone does not ensure safety; (3) Satellite geometry is a dominant factor—better geometry reduces missed detection risk and improves integrity. Other methods such as Solution Separation RAIM and ARAIM monitoring use position domain consistency rather than residuals, using Gaussian-based bounds instead of Chi-square. These methods will be explored in the coming issues.

Note: The concepts and the mathematics are mostly generated based on the following papers. Please consider these papers for detail understanding of the involved math and algorithms. The goal in this column is to demonstrate in a high level the impact of geometry on the Chi Square residual RAIM and the integrity.

Joerger, M., & Pervan, B. (2015). Fault Detection and Exclusion Using Solution Separation and Chi Squared RAIM. IEEE Transactions on Aerospace and Electronic Systems.

Joerger, M., Pervan, B., and Gratton, L., ‘Solution Separation RAIM: Mathematical Foundations, Algorithm, and Performance,’ Navigation, vol. 57, no. 4, pp. 267–284, 2010. Joerger, M., and Pervan, B., ‘Advanced RAIM for Future GNSS Integrity,’ IEEE Transactions on Aerospace and Electronic Systems, vol. 49, no. 1, pp. 472–487, 2013.

Uwineza & Farrell (2023) — RAIM and Failure Mode Slope: Effects of Increased Number of Measurements and Number of Faults (Sensors, Vol. 23, Issue 10)

Monthly Performance Remarks:

1. Satellite Clock and Orbit Accuracy:

• The performance of GPS, Galileo and Beidou remained similar. The clock of Galileo improved by a small Figure F 1: The evolution of the UTC time dissemination offset as broadcast by different GNSS constellations. Galileo constellation had an unstable period during the second half of 2023. The offset computed by the UTC(k) of the Galileo system had a large deviation (up to 18 ns as indicated in the daily navigation message broadcast value). margin. GPS PRN 20 is resumed from 30th September and had a large clock jump on the day when SVN 51 started in transition to PRN20. NANU was released for the operational change. QZSS analysis is excluded for further consistency check in processing and to identify degradation in orbits of one of the QZSS satellites.

• IRNSS URA values for all satellites indicate improved accuracy.

• IRNSS clocks show I02 satellite has consistently good clock and I10 satellite has consistently the worst clock (note: among IRNSS satellite clocks)

2. The UTC Prediction (GNSS-UTC):

• All constellation, except IRNSS, provided relatively stable predictions of the GNSS-UTC. IRNSS started to drift heavily in the second half of the month

References

Alonso M, Sanz J, Juan J, Garcia, A, Casado G (2020) Galileo Broadcast Ephemeris and Clock Errors Analysis: 1 January 2017 to 31 July 2020, MDPI

Alonso M (2022) Galileo Broadcast Ephemeris and Clock Errors, and Observed Fault Probabilities for ARAIM, Ph.D Thesis, UPC

Bento, M (2013) Development and Validation of an IMU/GPS/Galileo Integration Navigation System for UAV, PhD Thesis, UniBW.

BIMP (2024 a) https://e-learning.bipm. org/pluginfile.php/6722/mod_label/ intro/User_manual_cggtts_analyser. pdf?time=1709905608656

BIMP (2024 b) https://e-learning. bipm.org/mod/folder/view. php?id=1156&forceview=1

BIMP (2024 c) https://cggtts analyser.streamlit.app

Bruggemann, Troy & Greer, Duncan & Walker, R.. (2011). GPS fault detection with IMU and aircraft dynamics. IEEE Transactions on Aerospace and Electronic Systems – IEEE TRANS AEROSP ELECTRON SY. 47. 305-316. 10.1109/TAES.2011.5705677.

Cao X, Zhang S, Kuang K, Liu T (2018) The impact of eclipsing GNSS satellites on the precise point positioning, Remote Sensing 10(1):94

Chen, K., Chang, G. & Chen, C (2021) GINav: a MATLAB-based software for the data processing and analysis of a GNSS/IMU integrated navigation system. GPS Solut 25, 108. https:// doi.org/10.1007/s10291-021-01144-9

Curran, James T. & Broumendan, Ali. (2017). On the use of Low-Cost IMUs for GNSS Spoofing Detection in Vehicular Applications.

Dhital N (2024) GNSS constellation specific monthly analysis summary, Coordinates, Vol XX, Issue 1, 2, 3, 4

Dhital N (2025) GNSS constellation specific monthly analysis summary, Coordinates, Vol XXI, Issue 1

GINAv (2025). https://geodesy.noaa. gov/gps-toolbox/GINav.shtml

Goercke, L (2017) GNSS-denied navigation of fixed-wing aircraft using low-cost sensors and aerodynamic motion models, PhD Thesis, TUM.

GROOPS (2025) GROOPS Documentation and Cookbook. https://groops-devs. github.io/groops/html/index.html

Guo, Jing & Chen, Guo & Zhao, Qile & Liu, Jingnan & Liu, Xianglin. (2017). Comparison of solar radiation pressure models for BDS IGSO and MEO satellites with emphasis on improving orbit quality. GPS Solutions. 21. 10.1007/s10291-016-0540-2.

Guo F, Zhang X, Wang J (2015) Timing group delay and differential code bias corrections for BeiDou positioning, J Geod,

Hauschlid A, Montenbruck O (2020) Precise real-time navigation of LEO satellites using GNSS broadcast ephemerides, ION

IERS C04 (2024) https://hpiers.obspm.fr/ iers/eop/eopc04/eopc04.1962-now

IGS (2019) GNSS Attitude Quaternions Exchange using ORBEX

IGS (2021) RINEX Version 4.00 https://files.igs.org/pub/data/ format/rinex_4.00.pdf

InsideGNSS (2024) Working papers: upgrading galileohttps://insidegnss.com/ working-papers-upgrading-galileo/

Jiabo G, Xingyu Z, Yan C, Mingyuan Z (2021) Precision Analysis on Reduced-Dynamic Orbit Determination of GRACE-FO Satellite with Ambiguity Resolution, Journal of Geodesy and Geodynamics (http://www. jgg09.com/EN/Y2021/V41/I11/1127)

Kj, Nirmal & Sreejith, A. & Mathew, Joice & Sarpotdar, Mayuresh & Suresh, Ambily & Prakash, Ajin & Safonova, Margarita & Murthy, Jayant. (2016). Noise modeling and analysis of an IMU-based attitude sensor: improvement of performance by filtering and sensor fusion. 99126W. 10.1117/12.2234255.

Li M, Wang Y, Li W (2023) performance evaluation of real-time orbit determination for LUTAN-01B satellite using broadcast earth orientation parameters and multi GNSS combination, GPS Solutions, Vol 28, article number 52

Li W, Chen G (2023) Evaluation of GPS and BDS-3 broadcast earth rotation parameters: a contribution to the ephemeris rotation error Montenbruck

Liu, Yue & Liu, Fei & Gao, Yang & Zhao, Lin. (2018). Implementation and Analysis of Tightly Coupled Global Navigation Satellite System Precise Point Positioning/Inertial Navigation System (GNSS PPP/IMU) with IMUufficient Satellites for Land Vehicle Navigation. Sensors. 18. 4305. 10.3390/s18124305.

Mayer-Guerr, T., Behzadpour, S., Eicker, A., Ellmer, M., Koch, B., Krauss, S., Pock, C., Rieser, D., Strasser, S., Suesser Rechberger, B., Zehentner, N., Kvas, A. (2021). GROOPS: A software toolkit for gravity field recovery and GNSS processing. Computers & Geosciences, 104864. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.cageo.2021.104864

Montenbruck O, Steigenberger P, Hauschlid A (2014) Broadcast versus precise ephemerides: a multi-GNSS perspective, GPS Solutions

Liu T, Chen H, Jiang Weiping (2022) Assessing the exchanging satellite attitude quaternions from CNES/CLS and their application in the deep eclipse season, GPS Solutions 26(1

Montenbruck O, Steigenberger P (2024) The 2024 GPS accuracy improvement initiatives, GPS Solutions

Montenbruck O, Steigenberger P, Hauschlid A (2014) Broadcast versus precise ephemerides: a multi-GNSS perspective, GPS Solutions

Montenbruck O, Hauschlid A (2014 a) Differential Code Bias Estimation using Multi-GNSS Observations and Global Ionosphere Maps, ION

Montenbruck, O., Schmid, R., Mercier, F., Steigenberger, P., Noll, C., Fatkulin, R., Kogure, S. & Ganeshan, A.S. (2015) GNSS satellite geometry and attitude models. Advances in Space Research 56(6), 1015 1029. DOI: 10.1016/j.asr.2015.06.019

Niu, Z.; Li, G.; Guo, F.; Shuai, Q.; Zhu, B (2022) An Algorithm to Assist the Robust Filter for Tightly Coupled RTK/IMU Navigation System. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2449. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14102449

Schmidt, G, Phillips, R (2010) IMU/ GPS Integration Architecture Performance Comparisons. NATO.

Steigenberger P, Montenbruck O, Bradke M, Ramatschi M (2022) Evaluation of earth rotation parameters from modernized GNSS navigation messages, GPS Solutions 26(2)

Strasser S (2022) Reprocessing Multiple GNSS Constellations and a Global Station Network from 1994 to 2020 with the Raw Observation Approach, PhD Thesis, Graz University of Technology

Suvorkin, V., Garcia-Fernandez, M., González-Casado, G., Li, M., & Rovira-Garcia, A. (2024). Assessment of Noise of MEMS IMU Sensors of Different Grades for GNSS/IMU Navigation. Sensors, 24(6), 1953. https:// doi.org/10.3390/s24061953

Sylvain L, Banville S, Geng J, Strasser S (2021) Exchanging satellite attitude quaternions for improved GNSS data processing consistency, Vol 68, Issue 6, pages 2441-2452

Tanil, Cagatay & Khanafseh, Samer & Pervan, Boris. (2016). An IMU Monitor agaIMUt GNSS Spoofing Attacks during GBAS and SBAS-assisted Aircraft Landing Approaches. 10.33012/2016.14779.

Walter T, Blanch J, Gunning K (2019) Standards for ARAIM ISM Data Analysis, ION

Wang, C & Jan, S (2025). Performance Analysis of MADOCA-Enhanced Tightly Coupled PPP/ IMU. NAVIGATION: Journal of the IMUtitute of Navigation March 2025, 72 (1) navi.678; DOI: https://doi.org/10.33012/navi.678

Wang N, Li Z, Montenbruck O, Tang C (2019) Quality assessment of GPS, Galileo and BeiDou-2/3 satellite broadcast group delays, Advances in Space Research

Wang J, Huang S, Lia C (2014) Time and Frequency Transfer System Using GNSS Receiver, Asia Pacific Radio Science, Vol 49, Issue 12

https://cggtts-analyser.streamlit.app

Yang N, Xu A, Xu Z, Xu Y, Tang L, Li J, Zhu H (2025) Effect of WHU/GFZ/CODE satellite attitude quaternion products on the GNSS kinematic PPP during the eclipse season, Advances in Space Research, Volume 75, Issue 1,

Yao J, Lombardi M, Novick A, Patla B, Sherman J, Zhang V (2016) The effects of the January 2016 UTC offset anomaly on GPS-controlled clocks monitored at NIST. https:// tf.nist.gov/general/pdf/2886.pdf

Note: References in this list might also include references provided to previous issues.

Data sources and Tools:

https://cddis.nasa.gov (Daily BRDC); http://ftp.aiub. unibe.ch/CODE_MGEX/CODE/ (Precise Products); BKG “SSRC00BKG” stream; IERS C04 ERP files

(The monitoring is based on following signals- GPS: LNAV, GAL: FNAV, BDS: CNAV-1, QZSS:LNAV IRNSS:LNAV GLO:LNAV (FDMA))

Time Transfer Through GNSS Pseudorange Measurements: https://e-learning.bipm.org/login/index.php

Allan Tools, https://pypi.org/project/AllanTools/gLAB GNSS, https://gage.upc.edu/en/learning materials/software-tools/glab-tool-suite.

(3 votes, average: 3.00 out of 5)

(3 votes, average: 3.00 out of 5)

Leave your response!