| Applications | |

Global experiences with public private partnerships for land registry services: A critical review

The purpose of this paper is to provide an overview of experiences globally with LRS PPPs and privatization proposals. We present here the first of the three parts of the paper |

|

|

Preamble

Any engagement in dialogue on proposed changes to land registry services delivery, either through privatization or Public Private Partnerships, is a minefield. You need to have your eyes wide open, be well informed, ask the right questions, critically analyze, discern the hype from facts, and be prepared for the unexpected. Through this paper, it is hoped that the reader is better enabled to navigate the PPP and privatization minefields. Here’s a sample of the diversity of opinion from what may be encountered from both proponents and opponents:

“There’s no doubt, it’s been done around the world, so it’s been done in Canada, there are no concerns there, provided you’ve got the regulatory functions, which we do. ……We will retain the data and the information, which we do, there’s a ministry function that can be done, and to provide benefits through economy of scale, in addition for potentially other services that can be provided to the consumer.” Former New South Wales Premier, Mike Baird (2016).1

“I am very pleased to announce the appointment of Land Services SA to provide the State with a range of land services for a 40-year concession period – these services cover both landstitling and land valuation activities. ..The sale will deliver the State an upfront return of $1.605 billion now plus a considerable ongoing royalties stream over the concession period. This is an absolutely outstanding result for the State. …I am also very pleased to say that all protections for the people of South Australia, that I announced in last year’s budget, will be achieved, including indefeasibility of title, continuation of the current fees and charges regime, strong protections for privacy and data security, and maintaining current service delivery standards. ….South Australians will notice no change in the services they receive through these functions.” Hon. Tom Koutsantonis MP, Treasurer, South Australia (2017).2

“The recent agreement in April 2017 for New South Wales indicates the appetite for PPP is still active. When one looks at the organizations who bid for New South Wales, it is apparent that the large pension funds and banks will provide the investment required to modernize land administration.” Former Ontario Assistant Deputy Minister Art Daniels (2017).3

“Privatization is no panacea for profligate governments. Selling assets is a oneoff that provides only brief respite for those addicted to overspending……”The Economist (2015).4

“I’ve been a very strong advocate of privatization for probably 30 years. I believe it enhances economic efficiency [but] I’m now almost at the point of opposing privatization because it’s been done to boost proceeds, it’s been done to boost asset sales, and I think it’s severely damaging our economy.” Rod Sims (2016), Chairman, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission.5

“On the down side, the conversion of records to POLARIS took longer and cost far more than originally estimated. The arrangement is monopolistic to the detriment of other commercial interests and competition especially in respect of the value-added services. Ontario is now locked into a very longterm agreement with Teranet which could lead to complacency and a lack of incentive to evolve the ELRS in line with technological and other changes and increasing user expectations.” Independent Consultants’ review (2014) of Ontario Land Registry Services PPP under Teranet.6

The original version7 of this paper was prepared to inform professional colleagues in the Australian state of Victoria regarding a proposed PPP for land registries. Subsequently, it was cited by a number of organizations in their respective submissions to the Victorian State Parliamentary Upper House “Inquiry into the Proposed Long Term Lease of Land Titles and Registry Functions of Land Use Victoria”. 8 It was also cited in various media commentaries on the issues.9

Part a: understanding privatization and public private parterships

Introduction

Two of the most controversial microeconomic roles of government are its role in providing public goods and its role in dealing with market failure due to externalities.10 An understanding of the provision of public goods – which covers services and infrastructure – is critical in any consideration of alternative methods of service delivery (ASD) through the private sector. Public goods provide an example of market failure resulting from missing markets. Which “goods and services” are best left to the market? And which are more efficiently and fairly provided as “collective consumption goods” by the state?

Public infrastructure and services, have traditionally been financed, owned and operated by the public sector. However, especially over the past decades, governments have increasingly looked at ASD. Increasingly the private sector is delivering public services and infrastructure under government direction.

There have been many drivers for ASD including:

▪ seeking to realize an immediate upfront payment for privatization or leasing of government assets;

▪ fiscal constraints on the public sector preventing essential infrastructure upgrades;

▪ budget limitations to adequately fund operating costs;

▪ inefficient management of infrastructure by public entities;

▪ poor service delivery;

▪ weak public capacity;

▪ or policy decisions that sought to bring about change.

ASD has many modalities including privatization and Public Private Partnerships (PPP or P3). These are not one and the same thing, although there is a frequent tendency to use the terms interchangeably. The critical distinction between a PPP and privatization relates to ownership of the infrastructure, asset or facility. When a publicly-owned asset or facility is privatized, the ownership is divested from the government and permanently transferred to the private sector. Although government may maintain regulatory control, the private sector as the owner is accountable. This is not the case for PPP, where government retains ownership of the “asset”, the government defines the extent of private sector’s participation in the PPP, and the government holds ultimate accountability for the provision of the services. These distinctions are non-trivial, and for those reasons this paper includes a brief overview of ASD, of which PPP is one. Also, there are many different PPP modalities. Awareness of these distinctions are very important, to effectively engage in PPP dialogue. Having said that, using terms like “sale”, “divestment” and “privatization” are more likely to raise professional, political and public concerns than terms such as “lease” and “PPP”. Words do matter:

“The search for the mot juste [right word] is not a pedantic fad but a vital necessity. Words are our precision tools. Imprecision engenders ambiguity and hours are wasted in removing verbal misunderstandings before the argument of substance can begin.”11

So much of the debate may be side-tracked by imprecise terminology. Objecting to government’s proposal for a private partner to operate the Land Registry under a PPP cannot be argued that it is a sale or privatization. It is a contractual lease and it is under government regulatory control and contractual conditions. So, objections can easily be discounted unless they are both well-informed and well-framed and use the correct terminology. Even more difficult, is understanding the micro-economics on which decision-making may be based.

Canada’s Ontario Province LRS PPP, that commenced in 1992 for a twenty-five year period, was extended in 2013 until 2067. Governments and other advocates of LRS PPPs constantly refer to Ontario’s successes and as best practice – the “gold standard”. This paper intentionally provides a deep dive into the Ontario experience.

Therefore, the purpose of this paper is to provide an overview of experiences globally with LRS PPPs and privatization proposals. The paper is intentionally presented in three discernable parts: (i) Part A providing a background to privatization and PPPs; (ii) Part B specifically looking at country experiences; and Part C identifying major lessons and conclusions. In total, this report presents ten case studies – three from Canada, one each from the UK, Malaysia, Philippines, New Zealand and the final three from Australia. Through this paper12, it is hoped that people are better informed and can better advocate their interests based on evidence and facts rather than rhetoric and hearsay.

Alternative Methods of Service Delivery (ASD)

There are seven primary public service delivery modalities that are generally identified. In the list below, modalities 1-3 are delivery by the public sector, and modalities 4-7 are specifically ASD:13

1. Direct Delivery – Government delivers the service directly through its ministries, business planning, focusing on results, cost recovery, getting the best value for the tax dollar, and customer service.

2. Agencies – Government delegates service delivery to an agency operating at arm’s length from the ongoing operations of the government, but maintains control lover the agency. Creating a new non-profit organization to undertake activities that otherwise would be provided by government, or, in instances where profits might be generated, asking non-profits interested in delivering the services to bid for the opportunity.

3. Devolution – Government transfers the responsibility for delivering the service to: (i) other levels of government; (ii) profit and non-profit organizations that receive transfer payments to deliver the service.

4. Purchase of Service – Government purchases services under contract from a private firm, but retains accountability for the service. This includes contracting out and outsourcing of services. A government that wishes to cut costs can contract out the delivery of services to private firms. In cases where numerous firms are capable of performing the work, the government usually will put out a request for tenders. Once the competition has closed, the government then makes a decision based solely on price or on price and a combination of other criteria (e.g. quality of service and track record).

5. Partnerships – Government enters into a formal agreement to provide services in partnership with other parties where each contributes resources and shares the risks and rewards. This is more commonly referred to as the PPP.

6. Franchising/Licensing – For franchising, the government confers to a private firm the right or privilege to sell a product or service in accordance with prescribed terms and conditions. For licensing, the government grants a license to a private firm to sell a product or service that would otherwise not be allowed.

7. Privatization – Government sells its assets or its controlling interest in a service to a private unlike contracting out, where the government retains responsibility to provide a service even though it hires someone else to deliver it, privatization involves selling the service to the sector company, but may protect public interest through legislation and regulation. This alternative method of service delivery allows for greater competition over contracting out if the government allows for multiple firms.

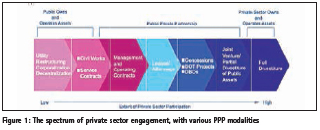

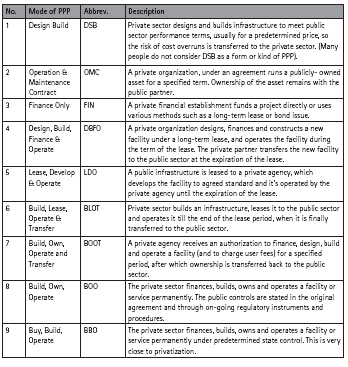

Partnerships with the private sector take a wide range of forms varying in the extent of involvement of and risk taken by the private party. The terms of a PPP are typically set out in a contract or agreement to outline the responsibilities of each party and clearly allocate risk. The following (figure1) depicts the spectrum of private sector engagement, with various PPP modalities occupying the middle sections of the spectrum:14

Although this may seem like too much detail, it is important to be familiar with the distinctions, as all too often terms are misused or used interchangeably.

Global endorsement of private financing

It is now globally significant that the July 2017 G20 Leaders’ Declaration endorsed:

“… the MDB’s 15 Joint Principles and Ambitions on Crowding-In Private Finance (“Hamburg Principles and Ambitions”) and welcome their work on optimizing balance sheets and boosting investment in infrastructure and connectivity.”16

The MDBs have agreed that their engagements to help countries maximize their resources for development, needs to be done responsibly without pushing the public sector into unsustainable levels of debt and contingent liabilities. As such, there should be a drawing on private resources when they can help achieve development goals, and reserving public financing for other sectors and services, where private sector engagement is not optimal nor available – hence the PPP approach. Essentially, it seeks to maximize financing for development by leveraging the private sector and optimizing the use of scarce public resources. However, the intended focus of the MDBs is on developing countries, and it should be important to keep that in mind when these arguments for PPP are proposed for developed countries, including Australia. Australia is a member state of G20.

PPP “101”

So, what is a PPP or P3? For the purposes of this paper, a common, widely accepted definition has been adopted: “PPP means any contractual or legal relationship between public and private entities aimed at improving and/or expanding infrastructure services.”17

Notably, PPP is about improving or expanding services, and adopting a suitable financing mechanism. Accordingly, the valid, strong justifications for pursuing PPP would be expected to include:

▪ Government finance is not available to operate, upgrade and sustain the service infrastructure;

▪ Expertise and competence are lacking in government, but are available in the private sector, especially relevant when major information communication technology (ICT) investment is required.

▪ The service culture within government is lacking, and cannot be remedied, so an externally operated service is best pursued. There are many types of PPPs, each with specific types of contractual or legal relationships. The following table is a summary of the commonly agreed PPP types:18

MDBs, as well as other international organizations including the European Commission, have made available online, many reports on PPP – all freely downloadable. Jeffrey Delmon (2010) has produced an excellent guide, which I would describe as the quintessential PPP “101”. Delmon advises:

“The decision to adopt PPP must be political, first. The government must consider the political and social implications of PPP and whether there is sufficient political will to implement PPP. Next, consideration needs to be given to the institutional, legal and regulatory context – the extent to which government institutions have the needed skills and resources, the financial and commercial markets have needed capacity and appetite, and laws and regulations encourage or enable PPP – and whether changes need to be made to the institutional, legal and regulatory climate in order to provide the right context for PPP. Once these basic issues have been addressed, those designing the PPP solutions available to policymakers must consider the most commercially and financially viable and appropriate structures. This must involve consideration of cost benefit, value for money, the sources of finance, the commercial arrangements, the nature of investors and government participants, and a variety of other circumstances that need to be addressed in the design of appropriate PPP structures. This latter process is where a robust classification model can help.”

Why do Governments pursue PPPs?

The potential benefits of PPPs to the government and the public, may include:

▪ Improved service delivery – PPPs are expected to improve service delivery due to the merger of both sectors.

▪ Higher levels of service through innovation.

▪ Value for money – PPPs are expected to be effectively managed, which brings about satisfaction.

▪ Improved cost-effectiveness – due to vast experience and flexibility, PPPs are expected to deliver public services more cost effectively than other traditional partnerships.

▪ Increased investment in public infrastructure – basic amenities such as hospitals, schools, highways, reduce government capital cost, helping embrace the gap between the need for infrastructure and financial capacity.

▪ Reduction of public sector risk – PPPs are expected to shift the risk from the public to the private sector.

▪ Delivery of capital projects faster – private investors are expected to be more flexible in nature and have greater access to financial resources from financial institutions.

▪ Improved budget certainty – the transfer of risk from public-private sector is expected to reduce costs usually set aside for unforeseen circumstances. Services are expected to be more cost effective and utilize public funds more efficiently.

▪ Better use of assets – private sectors are expected to maximize fully the potential and returns in investments.19

Turning to the other side of PPPs, what are the potential benefits to the private sector investor? These may include:

▪ PPPs can provide the private sector access to a more longterm investment opportunity.

▪ Business can be set up with security and certainty of procuring a government contract.

▪ Payment is initiated through a contracted fee for service, or by collection of user fees. Revenues are secure for the term of the PPP contract.

▪ Private sector partners, by maintaining a high level of efficiency, and through managerial, technical and financial capabilities, can expand their expertise, to other business opportunities, and even to other jurisdictions (states and countries) utilizing the successful PPP track records.20

Later in the report, the veracity of the potential benefits, in particular to government will be discussed – these go to the heart of the arguments of both proponents and opponents for PPP.

Ontario’s Auditor-General’s 2014 Annual Report was highly critical of PPPs: “Ontario Auditor General (AG) Bonnie Lysyk rebuked the Ontario government’s use of public-private partnerships for public infrastructure in a damning report that revealed P3s have cost the citizens of Ontario nearly $8 billion more over the past nine years than if the government had successfully built the projects itself. The AG found that while the province assumes there is less risk of cost overruns and other problems with P3s than with the public sector, the province actually has “no empirical data” to back up that assumption. P3s, meanwhile, are more expensive because companies ‘pay about 14 times what the government does for financing, and receive a premium from taxpayers in exchange for taking on the project.’

Lysyk also found that the entire process of evaluating the cost-effective ness of P3s in comparison to the traditional public procurement approach was replete with errors. The AG noted billions of dollars’ worth of double counting and other inappropriate calculations that demonstrated a clear bias in favor of P3s. According to CUPE Economist Toby Sanger, these P3 projects have created an estimated $28.5 billion in liabilities and commitments still outstanding to private corporations— a cost the citizens of Ontario will have to pay back in the future. Other P3 projects in Ontario would bring ‘total liabilities to over $30 billion owing to P3 consortiums and financiers, the equivalent of $6,000 per household.’“21,22

Canada is often described as the most active PPP market in the world, and is certainly one of the most mature dating from 1993. As at 2016, there have been some 244 PPPs, with 177 now closed and around 70 remain operational or pending.23 PPP is a well-established financing model in Canada adopted at federal, provincial and municipality levels:

“The life cycle of infrastructures, the Canadian geography and the current economic context are all convergent factors that favor this market. Also, the improvement of public infrastructures through the use of private capital is a concept which has always benefited from the support of the federal government.”24

Although PPPs can be a very useful and effective mode for the delivery of public services, that should not imply that PPP approach is appropriate for all public services delivery. Furthermore, moving to a PPP model should not just be about maximizing an initial lease fee and annual remittances and should be reviewed even further than the real return over the agreed life of the lease? Economists would be expected to advise government on how to maximize net social benefits through the PPP or privatization, and this is very clearly stipulated in the economic policies of many national treasuries including the United States:

“In short, a balance of elements – the project’s characteristics, the economic environment in which the project is being developed, and the ability of the project sponsor to take certain actions – jointly determines whether a PPP can deliver and operate a project that yields higher social welfare than would have been the case under conventional procurement. In other words, no one single factor informs whether a project yields a higher net social benefit as a PPP than under conventional provision, while providing a competitive rate of return for the private partner. …….

An essential prerequisite to achieving the potential net benefits of a PPP is for the government sponsor’s to fully understand the project’s characteristics and economic environment before initiating the procurement. In addition, successful PPP implementation requires executing a set of complementary best practices before the project gets underway. Not taking these steps may lead to higher costs, failure to meet performance targets later in the project’s life cycle, and a misallocation of scarce public resources.”25

Governments, including the states in Australia, are either failing to understand or just ignoring, the characteristics and economic environment for many PPP and privatization proposals. In July 2016, Australia’s lead watchdog, Rod Sims, the chairman of the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) advised that the privatization of public monopolies should cease because governments are mishandling them:

“…..says he has become so exasperated by the way in which governments are privatizing public assets that they need an ‘uppercut’.

He says governments have repeatedly botched the sale of airports, electricity infrastructure and major ports – making things worse for consumers – because, when selling the assets, they have been motivated by maximizing profits rather than making efficiency gains.

He says governments have created private monopolies without sufficient regulation to stop those monopolies overcharging users – and the public knows it and has a right to be angry.

‘I’ve been a very strong advocate of privatization for probably 30 years. I believe it enhances economic efficiency [but] I’m now almost at the point of opposing privatization because it’s been done to boost proceeds, it’s been done to boost asset sales, and I think it’s severely damaging our economy.’ ”26 ,27

Approaches to LRS PPP

The most commonly accepted PPP modalities for LRS would be LDO, BOO and BOOT. Both NSW and SA operated very effective, modern land registries using contemporary information technology (IT) infrastructures. Obviously over time updating will be required as required and it would be assumed that these are both LDO types. Similarly, the LRS of Ontario and Manitoba would be assumed to be LDOs, as a major reason given publicly for these PPPs was to fund computerization, for which the governments lacked funds.

LRS PPPs are typically long-term leases, such as Ontario extended to 2067, NSW is 35 years and South Australia is 40 years. The concessionaire needs to recoup the initial investment cost, and make a profit on annual operations. However, and quite frankly, after a period of 30-60 years, how would government resume operating a LRS? The government would most likely be lacking in capacity and human resources to immediately step in. If the event of an early termination of the lease for governance reasons, the private sector operators staff may not be able to be taken on board under government due to civil or criminal proceedings or key personnel may decide to take positions elsewhere. One cannot assume that the private partner’s personnel would be taken on by the government. There may be a court injunction issued that precludes immediate assumption of operations by government? NSW, SA and the Victorian governments all claim that the fail-safe risk mitigation is that government resumes full control. Governments will claim they have specific penalty arrangements in place contractually, but how would such measures be implemented when the company defaults and the government has little chance of taking back control of the operation in the short-term?

Interestingly, the Philippines, adopted a BOOT PPP modality for the Land Registry Authority (LRA, under the Department of Justice), with an initial concession period of just ten years. The reason why the Philippines adopted BOOT is that the land registration system was very much under-developed and the government lacked finance to modernize the system. Further, the LRA is a highly-decentralized organization with a Registry of Deeds (RD) in every Provincial Capital and major municipality and lacked suitable office accommodation in most locations, requiring significant civil works construction in many locations. It is now approaching 15 years, including 2 years of dispute 2004- 06, where the PPP stopped and the contract went into a protracted arbitration. Investor consortium partners changed and even the IFC pulled out. The contract subsequently morphed into a BOO arrangement and it seems that no-one raises the duration of the agreement anymore. It is unlikely to ever be returned to government.

There are constantly raised concerns about all LRS PPPs in areas such as fee increases, government access to land records and even the very ownership of the information itself has most definitely continued to be concerns in the Canadian Provinces of Ontario and Manitoba, as well as in the Philippines. Transparency and governance have been raised as ongoing concern. The Philippines, which operates a modified version of the Torrens System, adopted from the State of Massachusetts in the US, has many fraudulent titles. Fortunately, public land records are maintained by the Land Management Bureau (LMB) under the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR). But there are tensions in areas such as plans of subdivisions, surveying standards and maintaining cadastral base mapping.

There may be similar considerations for other jurisdictions, including Australia’s State of Victoria where a PPP is under consideration for the Land Registry. What happens to the Crown plans and records? Can there be an iron-clad guarantee that the Surveyor-General would be able to fulfil statutory functions under the Surveying Act 2004, without any limitations or restriction arising from the LRS private partner. The Victorian Surveyor- General’s responsibilities include:

▪ (a) setting standards for survey information

▪ (e) & (f) correct position and description of Crown boundaries – has been alienated from the Crown or subdivided

▪ (g) resolve disputes over boundary determinations resolve disputes over boundary determinations that affect the Victorian cadastre;

▪ (i) maintain records of the status of land in Victoria and verify and certify the status of that land

▪ (j) register Crown plans

▪ (k) to prepare, or cause to be prepared, sign or approve plans of survey under any Act

▪ (l) Co-ordinate and provide access to survey and other information relating to land

▪ (m) provide surveying services to government projects and land dealings.28

Typically, LRS PPPs attract a special type of investor – an investor which has a very long-term investment horizon of many decades, viz. pension or superannuation funds. This is certainly the types of investor in Canada, NSW and now SA. Victoria is also being eyed by such investors and is already a topic with the major Canadian pension investor in Ontario and Manitoba. Victoria is now in its sights. Investors in PPPs are usually long-term, buy-andhold investors, suiting OMC and LDO PPPs. Having said that there have been exceptions. For example, the Philippines LRA PPP attracted a consortium, the original investors including IFC, Samsung, Manila Ports and the Indian financier Infrastructure Leasing and Financial Services, Ltd. (IL&FS), which would seem to invest more for the medium term.

For the UK, full privatization (outright sale) was the preferred approach, although two PPP variants were also considered.

As has been seen through the media, many politicians and bureaucrats from the Australian States of New South Wales (NSW), South Australia (SA), Victoria and Western Australia have lauded the success of LRS PPPs, with particular attention given to Ontario and its private partner Teranet. The benefits espoused, as earlier mentioned, include better service delivery, costeffectiveness, accountability, innovation and the financial benefits of large upfront payments, annual royalties and decreasing public expenditure and debt. In many cases, there have been benefits. However, there has been a tendency to cherry-pick the benefits, ignore the negatives and downplay the risks.

Any government proposing a LRS PPP should be able to address all of the following considerations:

▪ Are PPPs the best approach for the operation of LRS in the digital age?

▪ What risks and mitigations are necessary?

▪ How does it impact consumers?

▪ Why have some proposed PPPs for LRS proceeded and others not

▪ What are the net social benefits?

▪ Can the government recover from failed LRS PPP?

▪ Can the government compel the PPP company to comply when it is in breach?

▪ Should PPP contracts be deemed commercial-in-confidence or open to public scrutiny?

References

1. Sydney Morning Herald, Dec 7, 2016.

2. SA Treasurer, Media Release, Aug 10 2017.

3. Daniels (2017), p. 40. Daniels was responsible for the strategic alliance that created Teranet.

4. https://www.economist.com/news/ leaders/21593453-governments-shouldlaunch- new-wave-privatisationstime- centred-property-9

5. https://www.theguardian.com/ commentisfree/2016/oct/03/now-wereflogging- off-the-land-registry-thisis- not-good-news-for-home-owners

6. ConsultingWhere Limited & ACIL Allen, 2014, Annex B, Section 8, p.21, review for New Zealand government.

7. Bell, K.C (2017) Traverse, Professional Bulletin of the Institution of Surveyors, Victoria, Australia, Part A of Two Part Report, No. 315- September 2017; Part B of Two Part Report, No. 316 – December 2017, Melbourne http:// www.surveying.org.au/docs/traverse/ TRAV315.pdf http://www.surveying. org.au/docs/traverse/TRAV316.pdf

8. https://www.parliament.vic.gov. au/epc-lc/inquiries/inquiry/944

https://www.parliament. vic.gov.au/images/stories/ committees/SCEP/Land_Titles/ EPC_58-12_Text_WEB.pdf

9. https://www.theage.com.au/ national/victoria/feegougingfears- over-proposed-land-registrydeal- 20171001-gys7vw.html

10. http://www2.pitt.edu/~upjecon/MCG/ MICRO/GOVT/Pubgood.html)

11. Gowers (1954), quoting an “anonymous civil servant”.

12. A shorter version of this report was initially prepared as a set of case studies some years back. However, this version of the report, prepared on the request of the President of the Institution of Surveyors, Victoria (ISV), has revisited the earlier report and updated the coverage, especially in light of developments in Australia in 2016-17. ISV has a committee looking at the government’s inquiry into leasing out the Victorian Land Registration Services (LRS) to the private sector, and this report has been prepared with the sole intention of informing ISV members. The author, a member of ISV, is a member of that committee. This report presents the views of the author, as the former Surveyor General of Victoria (1999- 2003), and does not present the views of any organization. All information cited was from public source materials or other available sources.

13. Daniels, 2017.

14. https://ppp.worldbank.org/publicprivate- partnership/agreements

15. A multilateral development bank (MDB) is an institution, created by a group of countries, that provides financing and professional advising for the purpose of development. MDBs have large memberships including both developed donor countries and developing borrower countries. MDBs finance projects in the form of long-term loans at market rates, very-long-term loans (also known as credits) below market rates, and through grants. Examples of MDB include the World Bank, Asian Development Bank, African Development Bank and so forth. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ International_financial_institution

16. G20, (2017), G20 Leaders’ Declaration: Shaping an Interconnected World, July 2017, Hamburg, Germany.

17. http://www.consilium.europa.eu/ en/press/press-releases/2017/07/08- g20-hamburg-communique/

18. Delmon (2010), p.8.

19. CCCPP, (2004).

20. Daniels, 2017.

21. Ibid.

22. CCCPA (2015), p. 12.

23. Ontario Auditor General, 2014 Annual Report, pp. 199-200

24. CCPPP (2016) overview of PPP is well summarized in: http://www.lavery.ca/ en/publications/our-publications/2986- overview-of-the-canadian-publicprivate- partnerships-market.html

25. ibid

26. https://www.treasury.gov/ resource-center/economic-policy/Documents/1_PPP%20paper_ FINAL%2005%2017%2016.pdf

27. https://www.theguardian.com/ commentisfree/2016/oct/03/now-wereflogging- off-the-land-registry-this-isnot- good-news-for-home-owners

28. https://www.theguardian.com/ australia-news/2016/jul/27/acccsrod- sims-says-privatisationsseverely- damaging-economy

To be continued in next issue.

(303 votes, average: 4.92 out of 5)

(303 votes, average: 4.92 out of 5)

Very useful and informative series of 3 articles – Nov, Dec and Jan. Much appreciated.

Great series of 3 articles. Very useful and balanced. Well done Dr. B.

Useful series of 3 articles. More comments placed with the final instalment Jan 2020. Many thanks Coordinates.

Great. Very informative.

Over the past few months I have come back to this series (3) articles on PPP. I have also referred to many colleagues. Outstanding!

Very informative – all 3 articles excellent.

Great – still very relevant

Leave your response!

MY NEWS

TDK launches STRIDE positioning software Rx Networks partners with Zephr.xyz to scale high-precision GNSS Hexagon signs agreement to expand global access to reliable positioning and geospatial services CHC Navigation brings PointX and StellaX to smart lawn mowing Aerospacelab to supply eight more satellites for Xona

More...Order both the copies for FREE!

PREVIEW THE BOOK

PREVIEW THE BOOK

________________________________________

The Drone Rules in India 2021

________________________________________

National Geospatial Policy of India 2022

________________________________________

Indian Satellite Navigation Policy – 2021 (Draft)

________________________________________

Guidelines for acquiring and producing Geospatial Data and Geospatial Data Services including Maps

________________________________________

Draft Space Based Remote Sensing Policy of India – 2020

________________________________________

National Unmanned Aircraft System (UAS) Traffic Management Policy – Draft

________________________________________

Advertisement

Interview

Sherman Lo

Senior research engineer at the Stanford GPS Laboratory. He also is executive...

Easy Subscribe

Previous Issues

- Vol. XXII, Issue 1, January 2026

- Vol. XXI, Issue 12, December 2025

- Vol. XXI, Issue 11, November 2025

- Vol. XXI, Issue 10, October 2025

- Vol. XXI, Issue 9, September 2025

- Vol. XXI, Issue 8, August 2025

- Vol. XXI, Issue 7, July 2025

- Vol. XXI, Issue 6, June 2025

- Vol. XXI, Issue 5, May 2025

- Vol. XXI, Issue 4, April 2025

- Vol. XXI, Issue 3, March 2025

- Vol. XXI, Issue 2, February 2025

- Vol. XXI, Issue 1, January 2025

View AllLog In

E-ZINE

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

View AllPartnership

17-18 September

Hyderabad, India

21 - 24 September 2025

Baška, Krk Island, Croatia

29–30 October 2025

Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

3-5,November

Calgary, Canada

3-5 November 2025

Florianópolis, Santa Catarina, Brazil

24 – 27 November, 2025

Dubai, U.A.E..

23 - 25 February 2026

London, UK

25-27 March 2026

Munich, Germany

31 March - 01 April 2026

Singapore

22-23, April 2026

Amsterdam, The Netherlands

7-8 April 2026

Washington DC, USA

8 – 9 April 2026

Dubai, UAE

28 – 30 April 2026

Vienna, Austria

21-23 May

Benidorm, Spain

11-13, May

Ottawa, Canada

12 - 13 October 2026

Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

View Past Events

Most Rated

Most Commented

Most Viewed