| Applications | |

Cleaning and conservation of river Yamuna in Delhi

Yamuna is the identity of Delhi. While the immediate cleaning operations include trash skimming, weed harvesting and dredging, these will have to be long-term, overarching the entire region |

|

|

Rivers have always occupied a central place in India’s heritage and ethos and have traditionally been sources of spiritual inspiration, cleansing and penance. A critical component of environment and our ecosystem, we have accorded divine status to rivers, worshipping them as a life giving mother. River conservation is one of the highest priorities and we have made Namani Gange a template in our mission of river conservation, particularly in urban areas. The establishment of ‘River Cities Alliance’ (RCA) comprising 95 river cities across the country is one such step in this direction. It aims to offer interesting solutions such as sponge cities, reuse of used water, river health monitoring, pollution control, water sensitive city design and floodplain management.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s message dated 10th. Feb 2023 for DHARA Forum, Pune

From times immemorial, the villages and the cities came up along the rivers that evolved the cultures. Among various Delhis, Shahjahanabad (17th Century), was built along the river Yamuna, a 1370 km long river emanating from the Himalayas and merging into the River Ganga at Prayag (Fig.1). The river Yamuna which had been the lifeline of the city, started losing its connections during the 20th century after the building of New Delhi. The Ring Road, thermal Power stations, industrial areas, waste dumping and sewerage treatment plants were located along the river Yamuna.

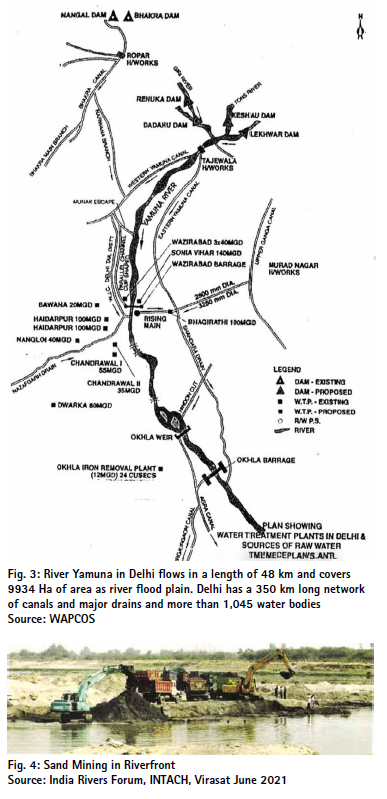

As a result, today the River Yamuna in Delhi has become a dirty drain. During the Delhi Assembly election (February 2025) the toxic water of the river Yamuna became a contentious issue. As committed by the Prime Minister Narendra Modi, the new government has to take up the river cleaning on priority so that the Yamuna becomes the identity of Delhi. While the immediate cleaning operations include trash skimming, weed harvesting and dredging, these will have to be long term, overarching the entire region. The river zone in Delhi covers 9934 Ha and the river flows in a length of 48 km. It is flanked by Hindon River in the East, and Sahibi River (Najafgarh drain) in the West (Figs.2 and 3). The Yamuna is integral to Ganga riverine systems connected by a network of natural stream, nallahs and canals. The river Zone in Delhi has been used for power stations, samadhis, housing, offices, stadia, temples, cremation ground, and an IT Park. Sand mining has impacted its water regime (Fig. 4). More than 161 unauthorised colonies have come up in this zone which discharge their effluents and wastes in the river. These have altered the river regime and endangered its water quality.

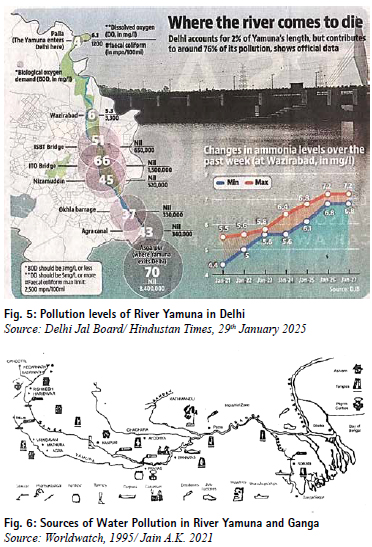

The figure 5 shows the dangerous levels of dissolved oxygen at 70 mg/litre against acceptable level of 6.1 mg /litre, faecal coliform as high as 84 million mpn/100 ml., against acceptable limit of 1200 mpn/100m, and ammonia level at 7.2 mg/l, against acceptable 3.0 mg/l.

The analysis of the water quality data in the river reveals the following:

• The levels of Dissolved Oxygen (DO) above the threshold limit (5 mg/ litre)

• The levels of Biochemical Oxygen Demand (BOD) above the acceptable limit of 3 mg/ litre.

• The dangerous levels of coliform (faecal and total) in the river water, mainly due to untreated sewage.

It is estimated that during last 50 years freshwater vertebrate in the river have declined by 83%, groundwater has depleted and there is a serious loss of biodiversity. The embankments to bind the floodplain have constricted the water f low, resulting into frequent flooding. With indiscriminate urbanization, industries, unsewered colonies, fly ash and garbage dumping, the river has become a corridor of filth, garbage, squatting and insanitation (Fig. 6).

About 90 per cent of river water is diverted into drains and canals upstream and most of the remaining water is stored for urban use, leaving the river high and dry, especially during the summer. River without a continuous flow lacks oxidation and becomes stagnant and polluted. A significant problem is eutrophication which drain and Supplementary drain. The relative quantification, results from the excessive levels of nutrients in municipal, industrial, irrigation and drainage effluents. Nearly 75% of pollution of river is from municipal sewage, and the balance coming from effluents generated from industries, run-off from agricultural fields, solid waste dumps, open defecation, etc.

According to Delhi Pollution Control Committee 28 major drains are falling into River Yamuna in Delhi which dispose of sewerage and wastes:

1. Najafgarh

2. Metcalf House

3. Khyber

4. Sweeper Colony

5. Magazine Road

6. ISBT

7. Tonga Stand

8. Civil Mill

9. Sen Nursing Home

10. Drain Number 14

11. Power House

12. Indra Puri

13. Sonia Vihar

14. Kailash Nagar

15. Shashtri Park

16. Barapulla

17. Maharani Bagh

18. Old Agra Canal

19. Jaitpur Drain

20. Sarita Vihar Pool

21. Tughlakabad

22. Drain near LPG Bottling Plant

23. Drain near Sarita Vihar Bridge

24. Shahdara

25. Sahibabad

26. Molarband

27. Abul Fazal

28. Supplementary drain

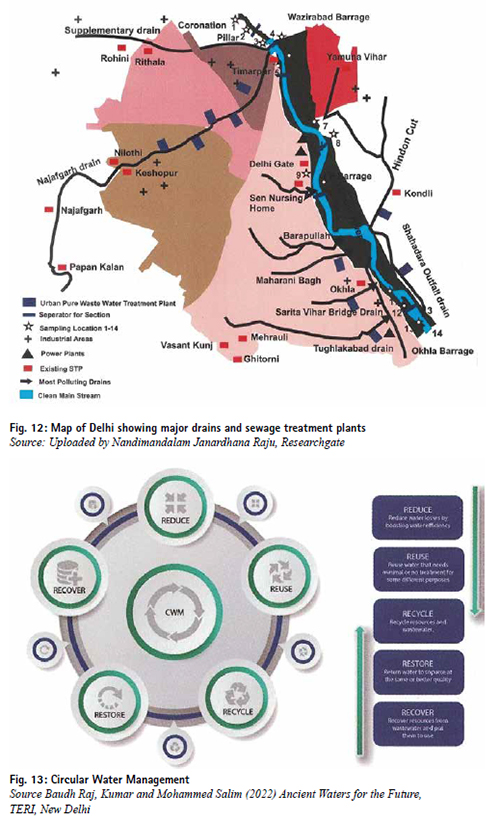

Against the disposal of 792 MGD sewerage, the current treatment capacity is only 550 MGD. New STPs have been planned at Okhla, Sonia Vihar and Delhi Gate. Rehabilitation of 3 STPs at Kondli Phase II, Rithala Phase I and Yamuna Vihar Phase II is in progress. Also the desilting of 10 trunk lines (200 kilometres) is in progress.

Besides 31 planned Industrial Areas, the Government of Delhi vide gazette notifications dated 2nd December 2005 and 30th June 2006 regularised 23 non-conforming industrial clusters in Delhi. These are without any safeguards for disposal of their effluents, that ultimately gets into the river through drains. In 2023, the Delhi Government initiated a study to assess the presence of microplastics in the river and identify potential sources of microplastic contamination and analyse leaching impact of microplastics on the river, Najafgarh drain and Supplementary drain. The relative quantification, nature source and characteristic of pollutants are essential to develop short-, medium- and long-term action plans.

Delineation of River Basin and Floodplain

Based on the topographical characteristics, the National Capital Territory of Delhi has been divided in to 6 drainage basins as follows: • Najafgarh Basin (332 Sq.Km.) • Alipur Basin (170 Sq.Km.) • Kanjhawla Basin (216 Sq.Km.) • Shahdara Basin (55 Sq.Km.) • Khushak Nallah – Barapulla Nallah System (95 Sq.Km.) • Mehrauli Basin (160 Sq.Km.)

Each basin has a main drain serviced by several tributary drains. The Gazetteers of Delhi 1883 and 1912 state that there were 65 species of fish in the river Yamuna such as mahseer, rohu, bachwa, mulley, tengra, silund, mohi, mirgal, lalbans, chilwa, gunch and katla, besides, turtles and gharials and magars [now extinct]. The Gazetteers record the river to be navigable all along. History books mention the boats from Delhi to Agra, Lucknow, Patna and Calcutta.

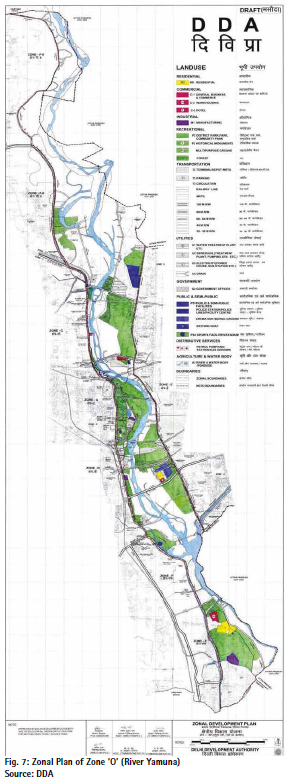

The National Green Tribunal (NGT) in its order on 6th February 2025 reminded the Delhi Development Authority (DDA) of non-compliance of its 2019 order to remove encroachments from the Yamuna floodplain and delay in Yamuna floodplain demarcation based on a one-in-100-year flood probability model. Earlier Delhi Government in its report dated September 18, 2024, had informed the NGT that a committee has been formed comprising district magistrate, Delhi Development Authority and the Revenue Department to assess the encroachments on the Yamuna floodplain. The legal demarcation of flood zone is a prerequisite for assessing the exact areas under encroachments in Zone ‘O’, the zonal plan of which stand approved in 2010 (Fig. 7). The orthorectified aerial images have been generated by interpretation of drone images, and ground surveys by the joint teams of DDA and Revenue Department. Authenticated ground coordinate details and submitted to the Geo-Spatial Delhi Limited (GSDL) for assessing the encroachments in the flood plain (Zone ‘O’), which are yet to be finalised.

The issue of demarcation of flood plain has been hanging since 1978 floods in Delhi. The Yamuna Standing Committee in 1978 recommended that the minimum spacing between future embankments on the banks of the river Yamuna be 5 km and the embankments be aligned at a minimum distance of 600 m from the ‘active river edge’. In 2006 Delhi High Court appointed Yamuna Removal of Illegal Encroachment Monitoring Committee headed by Justice (Retd.) Usha Mehra in WPC 689/2004 dated 29th March 2006. The Committee directed that no construction within vicinity of 300m on either side of the edge of the water channel of Yamuna River shall be allowed.

In 2014, the Committee constituted by National Green Tribunal (NGT) observed that “unfortunately its decision had not been followed and the flood water carrying capacity of the river had been greatly compromised”. In 2015, in a case filed by Manoj Mishra, the NGT formed a Principal Committee to identify all the existing structures in the floodplains and recommended that ought to be demolished. This is yet to be done.

As per the Delhi Master Plan 2021, the floodplain is termed as ‘Zone O’. In the Draft Delhi Master Plan 2041, the floodplains have sub-divided into Zone ‘O-1’ and Zone ‘O-II’. While no construction would be permitted in Zone O-I or the river (6295 Ha), regulated development will be allowed in ‘Zone O-II’ (3638.36 Ha). This will reduce the drainage capacity of the river by one-third. It will also have serious ecological consequences, besides increasing the frequency and extent of flooding.

Delhi has 3740 km of storm drains, of which the PWD and GNCTD own 2588km. The MCD, NDMC and Cantonment Board control a length of 475 km. The Irrigation and Flood Control Department controls 426.55 km, and 251 km are with the DSIIDC and NTPC. The DDA is responsible for preparation of Delhi Master Plan and the Zonal Plan of River Zone ‘O’, which integrate the plans of water supply, drainage and environmental control, etc.

Keeping the River Flowing

Dumping of solid and liquid wastes into the river Yamuna in Delhi not only violates the Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1974, and Environment Protection Act 1986., but also effects the environment flow (e flow) of water channel. Against the present e-flow of 0.86 million cubic metre/day, Yamuna in Delhi needs minimum 6.6 mcm/day e-flow. The Supreme Court of India in 1999 directed that a minimum10 cumecs of water be ensured in the river Yamuna throughout, together with pollution abatement and up-gradation of water quality to meet the burgeoning demand of water supply.

An Integrated Strategy

The river is intimately connected with the water supply, sanitation, flooding, drainage, and transport networks. As such, several agencies dealing with the environmental management and pollution control, land, water, flood control and drainage. power, irrigation, transport, and sewerage need to work together.

As such, Unified Centre for Rejuvenation of River Yamuna (UCRRY) was constituted vide DDA Notification dated 28th July 2015 under the Chairmanship of the Lieutenant Governor of Delhi to bring the diverse stakeholders/agencies on one platform.

The publication of the Centre for Science and Environment under the Namami Ganga Mission – Handbook for Planning and Designing Water Sensitive Cities for the Ganga Basin (2023) suggests watershed catchments as a basis for water sensitive design and conservation of existing water bodies and wetlands to optimise water harvesting and ecological sustainability. It stresses upon the revival of traditional water systems, and water harvesting by lakes, pond, catchment areas and wetlands. The INTACH has suggested installation of aeration and bioremediation systems to increase dissolved oxygen in water.

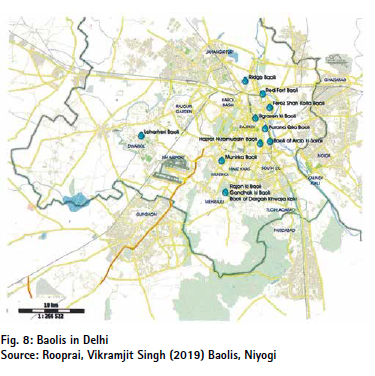

According to government records, Delhi had 1367 water bodies, ponds and lakes of which 1045 were found in the revenue records, but only 631 could be identified by field surveys. Of the 322 water bodies identified by Geospatial Delhi Limited (GSDL), only 43 were found on ground. Delhi also had about 65 baolis or stepwells (dug out water tanks), which collected rainwater. Vikramjit Singh Rooprai in his book Baolis (Niyogi. 2019) has listed 32 baolis in Delhi (Fig. 8 and Fig. 9).

The Delhi Jal Board has initiated the work on the rejuvenation of 155 water bodies including Jahangir Puri marshes, Najafgarh Lake, Mayur Vihar, Shahdara Lake, Neela Hauz, Hauz Khas and Hauz Rani. The rejuvenation of Najafgarh lake and Najafgarh drain (from Delhi-Gurgaon border to Wazirabad/river Yamuna-45 km) is being taken up by the I & F Department and DTTDC, GNCTD.

Circular Water Management

Rainwater harvesting and groundwater recharge are the essential tools of circular water management. This involves:

• Arresting groundwater decline and improving its accessibility water quality

• Preventing surface water run-off during monsoons

• Reducing water wastage and recycling of wastewater

A range of options for circular management of water include surface and sub-surface storage; net zero building design, recycling, and biological treatment of wastewater. A circular plan for water management incorporates the following strategies:

• Reviewing the Water Supply Standards

• Consumption efficiency

• Resource catchment

• Improvement in the quality of water when returning it to the environment

There is a huge potential for conserving water in the buildings, as only 5% of water is used for drinking or hygiene purposes, while 95% is used for evacuation of wastes.

The river, water bodies and wetlands need to be protected from ingress of the sanitation and sewerage. Recycling of wastewater and Zero run-off drainage with the provision of swales, retention ponds, etc. can help in optimizing the surface and groundwater. Adoption of new technologies, such as Blockchain and SCADA systems, can also help in a circular water management.

Creating balancing ponds for slow surface run off can immensely recharge the water table. The organic reed beds and aerators can clean the sewage entering the drains and replenish the aquifers. Drainage, integrated with rejuvenation of lakes, canal and riverfront can help to prevent flooding of urban areas, damage to roads and buildings and reduce risk of water-borne diseases. The South Greenways along Barapulla Nalla is being converted into a beautiful, lively area by primary water treatment, bioremediation, desilting sewerage by micro-STPs and wastewater recycling.

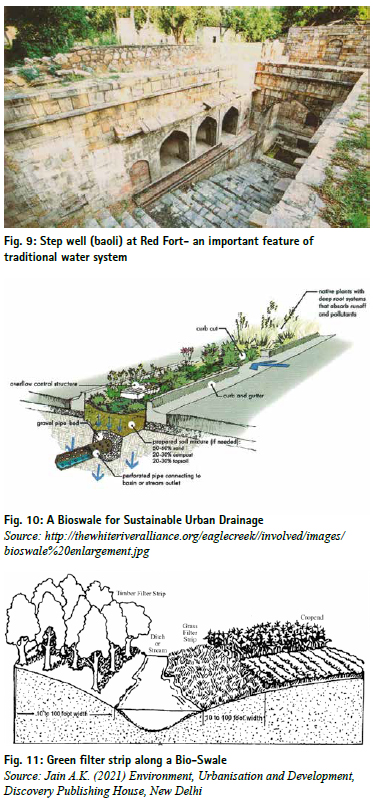

Based on natural topography, water catchment zones are identified and reserved of water bodies, parks and green strips, bio-swales, storage tanks and recharging pits (Figs.10 and 11). The storm water from the roads and unpaved areas can be conserved that enriches the groundwater. It is essential to put up decentralised wastewater and sewerage treatment facilities (Fig, 12).

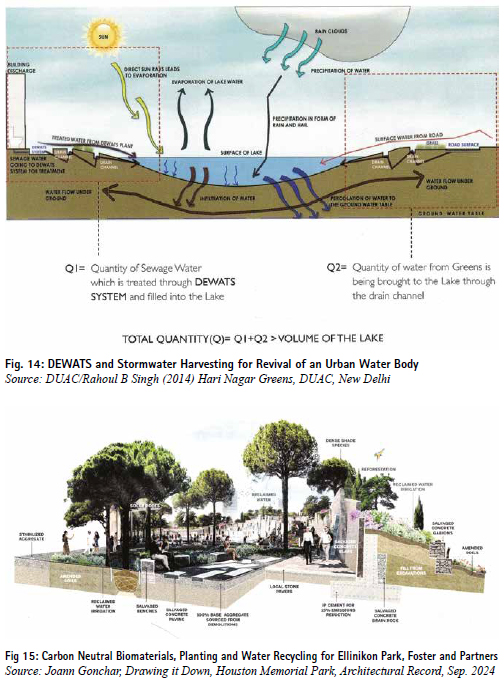

Circular Water Management focuses on the principles of reduce, reuse, recycle, restore and recover. Decentralised Wastewater Treatment System (DEWAT), bioswales and revival of water bodies are important tools for circular and sustainable water management (Figs 13 & 14).

The lakes, water bodies and riverfront can be rejuvenated and landscaped by recycled carbon neutral materials, planting and water recycling strategies (Fig 15). The soft landscape and vegetation along the riverbank allows rainwater to be absorbed rather than running off. Natural in-stream elements, e.g. root wads provide slow-water habitat for fish and insects that regenerate native wetlands and conserve the river biodiversity.

A Scientific Approach

A scientific approach to address the issues of river pollution needs building the interceptor sewers and STPs along the major drains to check its ingress into the sewage flowing into the river. This also needs augmenting the capacity of various existing STPs, such as Delhi Gate and Dr. Sen Nursing Home drains (from the existing 2.2 MGD to 15 million gallons daily each). The unsewered areas, viz. slums, unauthorized colonies, resettlement colonies, villages, etc. can be provided with alternative, decentralized sewage systems, such as Up-flow Anaerobic Sludge Blanket (UASB), sewage treatment through afforestation (Karnal Technology) and Constructed Wetland. Resource recovery options like methane generation, aquaculture and Bioremediation of the open drains carrying sewage can be adopted for reduction of pollution load.

For treatment of pesticide traces, capping the existing sand bed with bituminous charcoal or coconut shells can be an easy and inexpensive solution. Increasing flocculants by adding powered activated carbon (PAC) or bentonite clay with doses varying from 25-30 mg/l and the use of granular activated carbon can be effective, subject to its cost. Raw water tanks and rainwater storage can be protected by clay beds, which should be secured from getting washed away during the monsoons. The best way to get rid of the pesticides (non-point) and industrial toxins is through “source protection measures”, such as organic biological farming.

Restoration Projects for Yamuna Flood Plains

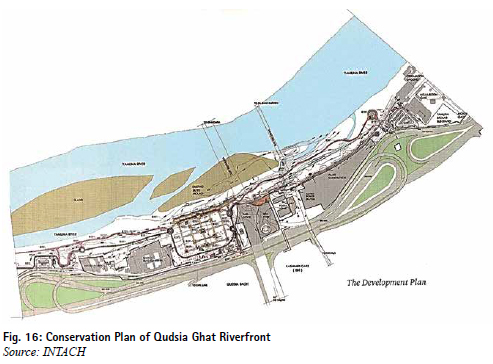

Several projects for restoration and landscape development have been taken up. An MOU was signed between the DDA and INTACH on 20th March 2019 under which the development plan of Qudsia Ghat (16 ha) has been taken up (Fig. 16).

The DDA and Delhi University’s Centre for Environment Management and Degraded Ecosystems have developed the following biodiversity parks:

• Yamuna Biodiversity Park near Wazirabad (183 Ha.)

• Aravalli Biodiversity Park near Vasant Vihar (278 Ha.)

• Northern Ridge Biodiversity Park near Delhi University (87 Ha.)

• Tilpat Valley Biodiversity Park near Sainik Farms (70 Ha.) • Yamuna River Front (O Zone) (97.70 Ha.)

• Neela Hauz Biodiversity Park near South Central Ridge (3.90 ha)

• Sanjay Lake Biodiversity Park near Mayur Vihar Ph-II (56.65 ha)

• Okhla Bird Sanctuary

Eco- Park at Tejpur Pahari near Badarpur border covering 10 acres (4 Ha) of the derelict mining pits has been f illed up with inert soil/good earth and landscaped.

Other projects include the following:

• Asita East Old Railway Bridge to ITO Barrage (98 Ha to109 Ha)

• Asita West Old Railway Bridge to ITO Bridge (93 Ha to107 Ha)

• Asita East Bird Sanctuary

• Amrut Biodiversity Park (108 Ha)

• Kalindi Aviral NH 28 to DND Flyway (100 Ha)

• Kalindi Biodiversity Park, DND to proposed Kalindi Bye pass

• Yamuna Vanasthali Wazirabad Barrage to ISBT Bridge

• Eco Tourism Area, Geeta Colony Bridge to ITO Barrage

• Mayur Nature Park and Hindon Sarovar NH-24 to DND Flyway

• Wetlands Restoration (19 Hectare) augmenting 5-6 lakh cumec of water

• Constructed Wetlands near Kalindi Biodiversity Park and Dhobi Ghat each treating 15 to 20 MLD of sewage

Bridging the Implementation Gaps

The cleaning and conservation of river Yamuna involves various States and Central Government, Departments and organisations. Its implementation is contingent upon meticulous planning, coordinated management, new technologies and financing. The Government of India has recently implemented some challenging projects, like Z morh tunnel in Sonamarg (J & K), Chenab Railway Bridge, Bagibeel bridge in Assam, Mumbai Trans Harbour Link (Atal Setu), Delhi Mumbai Industrial Corridor, PM Gati Shakti Master Plan, High Speed Railways, etc. Their successful implementation has been possible by innovative digital platforms as given below:

The PRAGATI (Pro- Active Governance and Timely Implementation) Platform, launched in 2015 by the Prime Minister has helped completion of more than 340 major infrastructure projects with effective resource utilisation, environmental sustainability and ensuring accountability. It leverages new technologies in planning, breaking the silos of departmentalisation to achieve synergy in project management. It has engaged Geo-Informatics and the geo-spatial planning tools that optimise the resources and reduce their environmental impact.

The Whole of Government Platform comprises over 1200 GIS based data layers from Central Government Departments and 755 from the States/ Union Territories, covering data of land, soil, geology, water bodies, forests, mines, revenue maps and administrative boundaries. It enables easier collaborations across departments for seamless implementation of the projects and plans. Citizen engagement becomes easier and viable by virtual town halls, and online consultation over plans and programmes.

Financing: Apart from the budget sources, innovative financing, such as Blended Green, Social and Sustainability Bonds (BGSSB) can be explored for financing. Other sources may include Urban Infrastructure Development Fund, Value Capture Finance, Land Banking, Tax Increment Financing, Impact Fee, Air Rights, Infrastructure Trust, EPC Contracts, Transit Oriented Development, Transferable Development Rights, Land Value Tax, Capital Gains Tax, Betterment Levy. However, the Yamuna Project should closely work with the National Mission for Clean Ganga (NMCG) and River Cities Alliance (RCA). Their experience of implementation and financing can provide important lessons for the Yamuna project.

In-Situ Community Engagement

In-situ community engagement stresses upon participatory, collective efforts for clean, pollution-free and pristine river. Besides formal regulations, local, community-based regulations are usually more effective with respect to water use, storage, pollution control and social audit. This poses certain challenges, like sensitising local communities towards conservation of river and water bodies.

It is also necessary to map the socio cultural activities, festivals and cultural resources and assess dependency of riparian communities on riverine resources. The local people can also help to deter illegal construction, sand mining and f ishing in the river. A judicious integration of ecological scientific research, digital planning and committed participation of the local communities can be helpful for a sustained connect with the river. The experience of Swachh Bharat Mission (SBM) indicates that besides a robust plan, legal framework and financial allocations, the success of a mission hinges upon changing the collective behaviour of the people. As such, the communities should be motivated to avoid disposal of sewage, effluents and other wastes in the river.

Conclusions

The River Cities Alliance (RCA) and the National Mission for Clean Ganga (NMCG) have initiated DHARA- Driving Holistic Actions for Urban Rivers. Its motto ‘Swasth Dhara- Sampann Kinara’ can be a theme to clean and conserve the Yamuna by five fold principles of nirmal, aviral, gyan, jan and arth. This would resonate the Yamuna with the identity of Delhi.

References

Acciavati, Anthony, 2015, Ganges Water Machine—Constructing a Dynamic Atlas of the Ganga River Basin Applied Research + Design Publishing, San Francisco, USA.

Amir, Sheeba and Ashim Manna, 2017, The Landscape of Water Access, My Liveable City, October-December

Baudh Raj, Kumar and Mohammed Salim (2022) Ancient Waters for the Future, TERI, New Delhi

Centre for Science and Environment, 2012, Down to Earth, New Delhi

CSE, 1997, Dying Wisdom: Rise, Fall and Potential of India’s Traditional Water Harvesting Systems, New Delhi.

CSE, 2001 Making Water Everybody’s Business: Practice and Policy of Water Harvesting, Eds. Anil Agarwal, Sunita Narain and Indira Khurana, New Delhi.

CSE, 2023, Handbook for Planning and Designing Water Sensitive Cities for Ganga Basin, CSE, New Delhi

Central Public Health and Environmental Engineering Organisation, 2014, Urban Water Supply and Sanitation, Ministry of Urban Development & Poverty Alleviation, New Delhi.

CPHEEO, 1993. Manual on sewerage and sewerage treatment, 2nd edition, Central Public Health and Environment Engineering Organisation, New Delhi.

Clay, Grady, 1979. Water and the Landscape, McGraw. Hill, New York.

Central Pollution Control Board 2018 Reports on Water Pollution in India, New Delhi.

CPCB, 2000. Status of water supply and wastewater generation, collection, treatment and disposal in class II towns, CUPS/49/1999-2000, Central Pollution Control Board, New Delhi.

Central Pollution Control Board, 2001, Constructed Wetlands for Wastewater Treatment, New Delhi. Delhi

Development Authority, 2010, Zonal Plan of Zone ‘O’ (River Yamuna Zone), New Delhi

DDA, 2007, Master Plan for Delhi-2021, New Delhi.

DUAC/Rahoul B Singh (2014) Hari Nagar Greens, DUAC, New Delhi DUAC/Amit Ghosal, 2016, Punjabi Bagh, Ward 103, New Delhi

Hindustan Times, 29th January 2025, Pollution Level of River Yamuna, New Delhi

Indian Water Resources Society, 1996. Theme Paper on Inter basin Transfer of Water for National Development – Problems and Prospects, New Delhi.

Institute for Human Development., 2000, India Water Vision 2025, Report of the Vision Development Consultation, New Delhi.

INTACH, 2015, Ecological Inventory of Yamuna River in Delhi, INTACH, New Delhi.

INTACH, 2015, Naturalising Delhi: A Plan for Enhancing climate Resilience, Urban Biodiversity and Habitat, Natural Heritage Division, INTACH, New Delhi.

Jain, A. K., 2021, Environment, Urbanisation and Development, Discovery Publishing House, New Delhi

Jain A.K., 2016, Rejuvenation of River and Water Resources, Discovery Publishing House, N. Delhi

MoUD, 2012, Improving Urban Water Supply & Sanitation Services, Advisory Note, Ministry of Urban Development, Government of India, New Delhi

Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs, 2014, Swachh Bharat (Clean India) Campaign, Government of India, New Delhi.

NEERI, 2005, Study on Rejuvenation and Environment Management of River Yamuna in Delhi, Unpublished Report for Delhi Development Authority, New Delhi

Roop Rai, Vikramjit Singh (2019) Baolis, Niyogi

World Bank, 1993, Water Resources Management: A World Bank Policy Paper. World Bank, Washington, D.C.

World Bank, 1998. India Water Resources Management – Urban Water Supply and Sanitation Report, Report No: 18321, Washington

Yes Bank, 2015, The Ganga Basin: Outthink Pollution and its Importance, New Delhi

http://thewhiteriveralliance.org/ eaglecreek//involved/images/ bioswale%20enlargement.jpg

(2 votes, average: 2.50 out of 5)

(2 votes, average: 2.50 out of 5)

Leave your response!