| Applications | |

Blockchain land registry best practices

The political and technical feasibility of harnessing blockchain technology to improve land administration |

|

|

|

|

Abstract

Property rights and trusted land administration are essential elements to the progress of any nation that is attempting to rise from poverty to wealth. Hernando DeSoto estimates that there exists in the world $20 trillion dollars’ worth of real estate owned by the world’s poor that is illiquid and ineligible to be used as collateral for loans because it is improperly titled. Blockchain, also known as distributed ledger technology, has the potential to radically change record keeping and the process of transferring title within the real estate industry. Blockchain land registries promise to increase land tenure security and transparency thereby leading to increased access to credit using land as collateral. This study catalogs political and technical obstacles to be overcome for the successful implementation of a blockchain land registry pilot. A comparative approach is employed to juxtapose pilot programs in both developed and developing nations.

Introduction

Property rights and trusted land administration are essential elements to the progress of any nation that is attempting to rise from poverty to wealth. Hernando DeSoto estimates that there exists in the world $20 trillion dollars’ worth of real estate owned by the world’s poor that is illiquid and ineligible to be used as collateral for loans because it is improperly titled. Blockchain, also known as distributed ledger technology, has the potential to radically change record keeping and the process of transferring title within the real estate industry. Blockchain land registries promise to increase land tenure security and transparency thereby leading to increased access to credit using land as collateral. This study catalogs political and technical obstacles to be overcome for the successful implementation of a blockchain land registry pilot. A comparative approach is employed to juxtapose pilot programs in both developed and developing nations. By combining surveys, interviews, and first-hand observation, the authors outline the major obstacles to establishing, and realizing benefits from, a blockchain land registry. After reviwing several cases and surveying professionals in the field, it emerged that political obstacles to the adoption of a blockchain land registry dwarf the technical challenges.

Blockchain technology, alternatively referred to as distributed ledger technology, is the technological framework that underpins cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin and Ethereum. The philosophical and technical mechanisms that enable a blockchain to function were unleashed on the world by way of an anonymously published white paper in 2008. The pseudonymous author, Satoshi Nakamoto, did not use the term blockchain in the paper on peer-to-peer electronic cash systems, but the clever code that enabled distributed ledger technology traces its roots to these humble beginnings. While the technology was initially utilized in the financial services industry by investors, currencies traders, and libertarian cypherpunks, a growing group of technologists and social scientists are realizing the potential applications for distributed ledger technology in solving a variety of problems stemming from deficits in social capital. Blockchain technology has the potential to be as disruptive in the future as the internet has been over the past several decades (Casey and Vigna, 2018). As is common with disruptive technologies, most analysts and observers overestimate the technologies impact in the short-term and underestimate it in the long-term.

Blockchain technology is essentially a digital, distributed ledger that lacks a central administrator. It is a further iteration of double entry accounting developed by Luca Pacioli in the late 15th century. The technology might also be compared to the law merchants of the middle ages who acted as intermediaries in abrogating the need for trust between merchants. The opening question of Milgrom, Douglass, and Weingast’s seminal paper on the role of institutions asks, “How can people promote the trust necessary for efficient exchange when individuals have short run temptations to cheat?” (Milgrom et al., 1990, p. 1). Modern blockchain technology has the capability to transform the way we think about trust institutions.

Technically speaking, a blockchain is a network of computers called nodes. These nodes use public key cryptography to ascertain the ordering and validity of transactions. When two parties transact on the chain, they use a combination of their private and public keys to submit the transaction to the nodes which then verify the validity of the transaction and add it to the chain. It is an append only data structure so once it is in the chain, it cannot be removed by anyone. If a malicious actor attempts to insert a false transaction, he or she would need to gain control over 51% of the hashing power, or nodes, of the network in a proof of work blockchain. This is nearly impossible because most chains have hundreds of nodes, each with the economic incentive to ensure that the integrity of the chain is maintained. Further explanation of this can be found, among other places, in Casey and Vigna’s (2018) seminal book, The Truth Machine. Blockchain economics is an emerging field of interdisciplinary study that delves into the incentives, rules and governance structures of blockchains. Public Choice Theory can elucidate the ways in which blockchain economics may affect the economy (Davidson, De Filippi, and Potts 2016). While not the focus of this paper, a basic outline of blockchain economics is presented here.

As Davidson and Potts point out, the gains realized by decentralized systems in economics were first enumerated by Adam Smith when he coined the phrase dynamic efficiency. Hayek, a champion of the Austrian School, further elaborated on the benefits of open, unencumbered markets in Law, Legislation and Liberty. Volume 1: Rules and Order (Hayek, 1973). The Austrian school’s focus on individual action and libertarian political theory meshes nicely with the economics of decentralized ledgers. The economic incentives of nodes in a blockchain network form a strong defense against malicious actors. Additionally, the decentralization of blockchain coalesces well with the Austrian’s emphasis on laissez-faire treatment of markets. There are two different overarching types of blockchains; public blockchains and private blockchains. Public blockchains utilizes proof of work consensus mechanism while private chains use other consensus mechanisms like proof of elapsed time or proof of stake. The most radical and libertarian minds prefer public chains because they are nearly anonymous and are free from any centralized authority; even governments. Enterprises prefer private chains because of their hybrid approach that allows for many of the transparency and immutability benefits of a public chain coupled with the ability to selectively grant access to the network. This is important because of the regulations requiring companies to know their customer (KYC) and antimoney laundering (AML) regulations.

Public blockchain enthusiasts, while many may not know it, are most closely aligned in their thinking with the Ludwig von Mises camp of Austrian Economics. Von Mises advocated a libertarian political theory that eschewed most government regulation of the economy. This fits well with public blockchains because they are free of any centralized control and provide a good deal of anonymity to users. The enterprise blockchain advocates like IBM Corda, and Hedera fall more in line with the thinking of Hayek. Hayek, the most famous Austrian Economist, was a bit less radical in his libertarianism and relied more on empirical models than did pure Austrians. One of the reasons for his popularity, in addition to his stellar reasoning and writing, was his ability to be flexible about the need for regulation of the economy in some circumstances. Just as enterprise blockchain companies understand the need for KYC and AML, Hayek knew the business and regulatory environment in which he was operating. Most enterprises will be weary of the radical nature of public blockchains and will opt for hybrid or private chains.

Blockchain in the marketplace

Here are a few market indicators that demonstrate the rise in blockchain adoption across a variety of industries. Approximately 34% of executives surveyed by Deloitte say that their company has initiated a blockchain deployment and 80% of businesses see blockchain as a strategic priority (ConsenSys, 2019). The Market Cap of all cryptocurrencies increased from $18 billion in 2017 to over $200 billion today. IBM alone has 1,500 industry and technical experts working on over 500 blockchain projects, several of which pertain to land administration (IBM Blockchain, n.d.).

The true value add in blockchain is a more efficient and transparent transfer of value in a trustless environment. In other words, it does not require third party verification due to the checks and balances of the distributed network of nodes, clever code and publicprivate key cryptography. According to IBM, blockchain technology adds irrefutable proof that a transaction occurred because of these four qualities: consensus (agreement that a transaction has occurred), provenance (history of transactions), immutability (an appendonly data structure), and finality (an agreed source of truth). In the context of land administration, one could see how these four qualities would provide gains in efficiency and effectiveness. The real estate industry is “plagued by inefficient processes and unnecessary transaction costs defended by selfinterested professionals and institutions” (Baum, 2017, p. 1). While there is much to be gained in the United States with respect to efficient land markets, there is even more to be gained in developing countries. Analysts at De Soto Inc. estimate that there exists in the world $20 trillion dollars’ worth of real estate owned by the world’s poor that is illiquid, under producing, and ineligible to be used as collateral for loans because it is either improperly titled or not titled at all (DeSoto, 2000). The introduction of blockchain based land registries could greatly increase not only liquidity in land markets in OECD countries, but also unleash millions of acres/ hectors of land to be used as collateral for loans in developing countries. Blockchain land registry pilot programs are underway in South Burlington Vermont, Chicago Illinois, Wyoming, Zambia, Rwanda, Colombia, Georgia, Sweden, and several states in India.

There are several blockchain technology companies working in the real estate, and specifically the land administration, industry vertical. The most influential include, ChromaWay, Medici Land Governance, and Propy. While there are several other blockchain real estate companies with large valuations and revenues, these three are unique in that at least part of their business model involves working with governments to streamline land administration and recording of titles. ChromaWay is a blockchain technology company that operates in multiple arenas with land administration just one of four main areas of service offerings. Medici is the leader in blockchain land governance solutions for the developing world and does some work in OECD countries as well. Propy is a more traditional real estate firm that is working to disrupt the real estate marketplace in the developed world. Their blockchain services include land administration services for the recorder’s office and various other market-making services.

A blockchain solution for land administration

Prior to the description of the processes inherent in most blockchain land registries, a definition of terms is required. The most pivotal and novel phrase in this process is a smart contract. Smart contracts are “selfexecuting contracts with the terms of the agreement between buyer and seller being directly written into lines of code. The code and the agreements contained therein exist across a distributed, decentralized blockchain network. The code controls the execution, and transactions are trackable and irreversible” (Frankenfield, 2019). The other phrase with which the reader will want to be familiar with is public-key cryptography. This describes a form of cryptography that utilizes pairs of keys, one of which is public and one of which is private. The owner of the private key is the only person with knowledge of that key but the public key can be known by anyone that would care to look. Encrypted code or text can be decrypted with a private key so that only the owner of the private key could view it. Lastly, a hash, is an algorithm that takes an input and transforms it into a smaller output. In many blockcahin applications, the SHA256 hash algorithm is employed which converts inputs into outputs of 256 bits. This translates to a string of numbers and letters that is exactly 64 characters in length.

Each company involved in the development of a blockchain land registry constructs the process differently, but they generally follow a similar pattern, and most utilize private or hybrid blockchains. First, a distributed registry is established with pre-written rules coded into the smart contract. The registry has a user interface that is accessible to buyers, sellers, lenders, attorneys, appraisers, the land office, and the public. In each transaction, the smart contract rules grant permissions to various actors based on their role in the transaction. The public will have the fewest permissions but enough to view transaction histories and ownership. The land office and other parties with a need to see deeply into the transaction will have the broadest permissions. Buyers and sellers use a combination of public and private keys to validate their role in the transaction.

A transaction flow might follow a pattern such that the buyer and seller agree to the terms of the sale and the terms of the smart contract. Following this, appraisers and lenders conduct their due diligence and upload their findings on the blockchain registry in accordance to the procedures laid out in the smart contract. The purchaser would then submit the down payment to the smart contract escrow account.

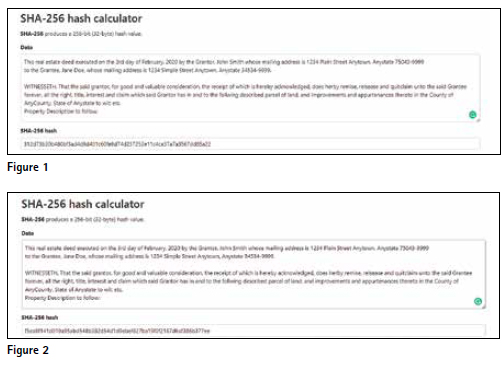

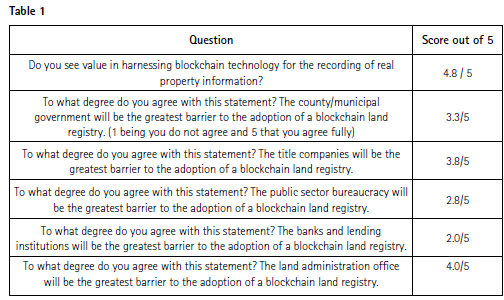

Following this, the lender would submit the remaining payment to the same smart contract escrow account. The smart contract would then execute by sending the funds in escrow to the seller while simultaneously sending the token representing title and ownership to the buyer and changing ownership status in the registry. This process is self-actuating but is visible to and auditable by the land administration office. All of these aspects to the transactions are stored on the blockchain in hashes in order to minimize the amount of data that is stored on chain. Full copies of all information can be stored off chain with hashes and metadata that are on chain pointing back to the source documents. We can be sure that no one has changed even a comma in these documents because if something even as small as a comma or a single digit were changed, the hash would change dramatically. Figure 1 depicts the output of a title record when it is hashed with a SHA-256 algorithm. Figure 2 depicts this same title record with the addition of a single comma. As you can see, any attempt to add or change any letter or number or even spacing, on the document will generate a completely different hash.

Literature review

The literature review outlines previous studies on the connection between property rights and investment specifically around the land titling space where ownership security is increased by trusted land administration institutions. There is a diverse and expansive literature on property rights and land reforms in the realm of land administration. This paper will limit its scope to property rights involving real property and liberalizing land reforms in the area of titling and land registries. The second half of the literature tackles the literature on blockchain land registries specifically.

Property Rights are defined as control over the land itself and “return to the assets that are produced and improved” (Rodrik 2000, p. 4). Secure land rights are more broadly defined as a continuum of tenure security where the owner perceives that he or she will enjoy the benefits of ownership and there are limited chances of expropriation (Henley, 2013). In this context, expropriation is defined as confiscation of the real property or fruits of production by the state or other powerful entities. This leaves some room for more traditional and informal structures but not to the point at which the real property could be described as communal. The literature is divided into two main positions, authors who support the premise that increased property rights leads to increased investment and therefore greater societal well-being, and authors who are unconvinced of this connection. Empirical studies do not predominantly support either camp, but rather, fall between these two groups with the preponderance of the evidence falling towards a positive effect on economic growth. The majority of those that are unconvinced of the connection are not claiming that an increase in property rights has a detrimental effect, but rather, that the evidence is mixed and is obscured by a litany of confounding variables that differ from place to place and culture to culture.

In the seminal work produced by the UK Government’s Overseas Development Institute (ODI), Henley (2016) identifies three frameworks for examining the causal effects of increased property rights specifically on agricultural investment. While this work finds mixed effects on the benefits of private property rights, the authors cite several prominent proponents of property rights from the development literature.

The first framework, the security effect, was originally posited by Besley and Ghatak (2009) and states that land owners invest more in their property and reap greater rewards when they have confidence that their land will not be expropriated and that they can keep the fruits of the land. The same authors provide the second framework, the gains from trade effect, investment will increase when efficient land markets allow for land owners to maximize their comparative advantage based on whatever factor of production they have in the most abundance. This second framework is of particular relevance in this paper since the title and property registry functions normally fall under efficient land markets. The third framework, and most important for this research, is the collateralization effect put forward by Hernando De Soto. De Soto argues that land owners, who previously may have been unable to access the productive capacity of their largest asset, can use the title of their land as collateral for loans (De Soto, 2000).

In the camp of authors that are more skeptical about the positive effects of property rights, the argument goes that existing property rights systems are a product of the culture and institutions in which they are found and provide sufficient incentives for investment without the need for land reform or formalized property rights (Braselle et al., 2002 and Fenske, 2011). There is a logic to this argument, but the authors still provide evidence that land administration is significant in investment outcomes for a variety of investment types. Fenske (2011) admits that tenure is significantly linked to investment outcomes in regards to fallow plots and tree planting and only finds it insignificant as it pertains to investments in labor and fertilizer. Might it be that the labor practices are culturally engrained and may take many years to change? In this case, the land owner with capital to spare would likely choose to invest in other areas of productivity. And might limited access to fertilizer be a reason why a land owner with capital to expend would find a different avenue through which to increase his or her land’s productive capacity? Brasella et al. (2002) provide a clear and convincing criticism of the aforementioned relationship between land tenure security and investment by noting that there is an endogeneity problem with the majority of studies on the topic. It is possible that greater investment leads to a greater sense of security for a variety of reasons such as establishing facts on the ground or such that the community observes the investment and is more likely to support the land owners rights thereafter. This presents the most logical argument regarding the ambiguity of the causal arrow between these variables. Brasella and her colleagues might be right, but the vast majority of academics conducting studies on this topic find a positive correlation and evidence for causation between secure land tenure and investment and make convincing arguments that the causality of this relationship begins with stronger property rights especially land tenure security. Additionally, Brasella and her colleagues only looked at one country in their study which can hardly be considered representative.

In another single country study that questions the causal arrow of property rights and development, Galiani and Schargrodsky (2010) found that property rights did lead to greater economic development, but not in the way that most authors within the literature find. They found that it was the increase in human capital that led to poverty reduction in the particular portion of the slums that enjoyed robust property rights. The authors did not do a good job parsing out the human capital variable to show that it is exogenous to other factors described previously. It does seem logical that investment in human capital would increase as the wealth of a neighborhood increases, and this would be a driver of poverty reduction. However, the authors overstep by claiming that the formalization of land and access to credit are not factors in this process. The natural experiment was not set up to effectively test access to credit or the utilization of land as collateral, and it seems likely that increased investment in human capital and increased access to credit are not mutually exclusive.

There is a group of academics that do not see private property rights as an important variable in economic growth. They range from those that think that private property rights are overrated (Trebilcock, 2008), to those that think they are harmful in some situations (Glaeser et al 2004; Fogel 2004; Schmid 2006; Leeson and Harris, 2018). Schmid (2006) argues that uncertainty around property rights can actually be a driver of growth by unshackling entrepreneurs so that they are not too constrained by reimbursing property owners if their quest for innovation becomes a bit destructive. Schmid’s analysis looks at westward expansion in 19th century and finds that the lack of defined property rights created an environment for innovation. There certainly was dynamic economic growth during this period and if the lack of property rights had anything to do with it, this finding does not travel as the opening up of millions of acres of nearly undisturbed land is a one off.

The most convincing sub-strain in the literature that argues against the connection between property rights and growth is that made by Daron Acemoglu his 2005 article about institutions. He cautions that property rights can entrench the well-off at the expense of the poor by creating a rent- seeking class of property owners and a subservient class of impoverished renters (Acemoglu, 2005). While Acemoglu is a champion of property rights as can be seen in his most recent book, Why Nations Fail, he is most concerned about inclusive institutions. He would say that it is better to have private property rights than not, but we must ensure that institutions are inclusive and not merely the mechanism through which the educated and elites can concentrate more power. Advocates for private property rights should take pause here and realize that, just as free markets do not always “work,” private property rights are amoral and can lead to harmful externalities in some situations.

Acemoglu’s concerns about rent-seeking elites was taken to extremes in one of the more recently published articles on property rights. Leeson and Harris (2018) do not mince words in the title of their article; Wealth Destroying Private Property Rights. They argue that the decision to privatize the commons is made by elites, and when the elites have a stake in the social wealth generated by the commons, they make good decisions about when to privatize. However, when elites do not have a stake, they may choose to privatize the commons even if that decision leads to a destruction of social wealth. The authors in this instance look mostly at African communal property and do not adequately account for issues of corruption and patronage that have coincided with many privatization schemes in Africa (Boone, 2007). With that said, they are correct that it is not entirely clear that all communal property should be privatized. There are valuable uses for the commons and institutions can be developed to administer them effectively (Ostrom, 2003).

The majority camp posits that increased access to capital, security in the asset and formalization of the asset is the mechanism that boosts the economic productivity of the asset’s owner (DeSoto, 2000; Pejovich, 1990; Bethel, 1999; Hayek, 1973; Coase, 1998; North, 1973 & 1991; Rodrick, 2004; Demarest, 2009; Clague et al., 1994; Leblang, 1996; Olsen, 1993; and Rand Corporation, 2009). Others ascribe the benefits of property rights to human capital investment, government investment in social services, or other tangential benefits.

Leblang (1996) is laser focused on property rights as a driver of economic growth, but most others in this camp are equally concerned with other variables such as social norms, societal capital, geography, and history. One of the most thoughtful and oft cited scholars to engender this viewpoint is Jean-Philippe Platteau. In his book Institutions, Social Norms and Economic Development, he unpacks the variables that either support or degrade the effect of property rights on economic growth by their presence or lack thereof (Platteau, 2000). In a similar vein, Douglass North (1991) places a good deal of emphasis on institutions and the way they shape commerce and specifically, property markets. In addition to incomplete information, “transaction costs in political and economic markets make for inefficient property rights.” Further highlighting the role institutions play, Ronald Coase demonstrates in “The Problem of Social Cost” that institutions play an outsized role when transaction costs are high (Coase, 1960). While North and Coase are referring to institutions more broadly, their observations include the institution of property rights. The importance of understanding transaction costs in politics and economics has proved enduring and will be revisited throughout this paper.

Likely the most well-known academic to champion property rights and, specifically, land titling programs, is Hernando DeSoto. In the opening pages of his seminal work, the Mystery of Capital, he describes the poor in developing countries by saying that “they have houses but not titles; crops but not deeds; businesses but not statutes of incorporation. It is the unavailability of these essential representations that explains why people who have adapted every other Western invention, from the paper clip to the nuclear reactor, have not been able to produce sufficient capital to make their domestic capitalism work” (DeSoto, 2000, p. 49). One would be hard pressed to find a more concise statement about the need for property rights in the developing world. DeSoto’s influence and charisma has been behind most of the recent land reform in Peru and in many other countries as well. His team of researchers estimates that there is twenty trillion dollars of capital locked up in the land holdings of the poor in developing countries because there are significant issues with the titling of their land (DeSoto, 2000). If they were able to gain access to a reliable titling system for their land, they could use this asset in the formal economy to generate wealth.

In developed countries, the idea of property rights is so engrained in our social and legal fabric, that people are not quite sure what a world without those rights would look like. In fact, they likely have not thought to imagine such a world (DeSoto, 2000; World Bank, 2010). At this point, the institution of property rights, especially as those rights relate to land, has taken on a heuristic quality in that there is no need to think critically about something so logical. This is not to say that there are not those in the West who argue for more communal property and less private property, but rather, that the knowledge about how the current institution of private property developed has been lost to our collective memory. Private property and sound land governance is one factor that has enabled Western countries to develop economically at such a blistering pace (DeSoto, 2000; Pejovich, 1990; Bethel, 1999; Hayek, 1973; Coase, 1998; North, 1973; Leblang, 1996). China’s meteoric rise presents a challenge to this theory at first glance. However, there are a few reasons why, after further inspection, China is less problematic. China abolished private property early on and in the cities in 1982, but then quickly changed tack and in 1994, allowed for 70-year leases of residential property and slightly shorter leases on commercial property (Clark, 2017). It remains to be seen what will happen as some of the leases begin to expire, but it is almost as if this is a face-saving measure as the Communist Party admits that private ownership and cultivation of property is essential to growth. It was in the 1990s and 2000s that China’s growth really took off with GDP growth averaging around ten percent per year for several years.

The institutional quality of land governance and the surrounding rights is of paramount importance. The empirical studies described above show that cadaster and land administration systems cannot be copied and pasted from the developed world onto the developing world because of the unique social and historical traditions in each country and the lack of institutional memory for such a system. The legal institution of property rights that supports an efficient land market does not fit into the “more formal and indigenous rights to land found especially in developing countries where tenures are predominantly social rather than legal” (World Bank, 2010).

Another difference between developed land administration systems and developing ones stems from transaction costs. Elucidated by the great Ronald Coase (1960), transaction costs can include market research, enforcement of property rights, and bargaining costs. An enlightening study conducted by Harvard academics in an impoverished area of Peru elucidated one of the nuanced aspects of land tenure reform. The study found that government titling drives did not necessarily increase access to credit when the funds are sought from a private lender but it did for public lenders (Field and Torero, 2006). However, they did find that homeowners with titles are 10% more likely to “have undertaken housing improvements in the last two years prior to the survey” and that “titled households are 15% more likely to finance improvements through formal loans” (Field and Torero, 2006). The land title availability did increase access to credit from public lending institutions, but for access to capital to make a demonstrable effect on a community, private lending must also be part of the equation. The main reason the authors gave for this lack of private lending was that of transaction costs. The cost of collateral processing, confirmation of title, foreclosure, and resale are immense relative to the small size of the loans requested by many of the urban poor. This issue of transaction costs is not one that should be quickly overlooked as it can be a major driver in “credit rationing” in developing countries (Coase, 1960; Field and Torero, 2006). The authors tackle another interesting challenge by teasing out the effects on demand for credit from the effects on supply of credit. We agree that it is an interesting academic inquiry to understand the nuance between the effects of property titling on supply and demand of credit, but it is even more interesting and relevant to get at how the process of increasing access to credit can be improved through technological advances in land titling.

The World Bank Report on Land Administration and Governance provides several examples, mostly from the developing world, in which corruption in land administration and governance have derailed development. For example, they note that in places like Kenya, India, Tanzania, Ethiopia and Bangladesh, to name but a few, corruption within land administration and governance is a major obstacle to economic growth (World Bank, 2010). In Honduras, around 80% of land held by private individuals is either untitled or incorrectly titled (Collindres et al., 2016). To make matters worse, a 2015 audit of the Honduran land titling entity uncovered more than 700 irregularities, most of which were related to “criminal acts of corruption” (Collindres et al., 2016). The system is highly politicized in that elected officials change titles for key supporters or refuse to enforce the titles of political opponents. In India, it is estimated that 66% of all civil cases in the court systems involve disputes over land (Thomason Reuters Foundation, 2016). Millions of these cases are currently awaiting adjudication in the backlogged Indian court system. It is estimated that the lack of land rights in India is a greater cause of poverty than illiteracy and the caste system (Kanojia, 2015).

As one might expect with such a novel concept, there are but a few strains in the blockchain based land registry literature. The first group to write on the subject were technologists and academics with some level of tech enthusiasm who foresee myriad applications for blockchain technology in the social sciences (Casey & Vigna 2018; Collindres et al. 2016; Scott, 2016; and Snall 2017). There is another strain in the literature that can be described as the “not yet” group (Vos 2017; and Lemieux 2016). These authors recognize the potential of blockchain in land administration but feel that the technology is not mature enough to replace legacy systems of land registration. The last strain in the literature are those that feel blockchain technology is not the right fit for land administration (Barbieri and Gassen, 2017). The following arguments posited by the various subgroups in the literature were on display at the 2017 and 2019 World Bank Conference on Land and Poverty in Washington, D.C.

The enthusiasts argue that blockchain technology in land registries has the potential to open up the credit market for those who would normally not have access (Scott, 2016), curb corruption (Collindres et al., 2016), and minimize transaction costs (Casey and Vigna, 2018). These are all theoretically feasible but are not without obstacles. To dwell on the obstacle, though, is to miss the potential upsides of a successful implementation of a blockchain based land registry. The economic vitality and productivity of the world’s poor are severely hampered by informal property arrangements and their inability to access credit markets (DeSoto, 2000). A blockchain based land registry that made records transparent to all citizens could reduce transaction costs and establish a function market for immovable property. USAID did a study in Uganda in which they found that the land of those who were secure in the property rights was 63% more productive than those who had a fear of eviction (USAID, 2016). No doubt there is room to critique how they measured the increase in productivity, but it is telling that organizations like USAID and the World Bank have been some of the first to champion innovation in the property registry space.

As described previously, the second strain in the literature represents a group that is more cautious than optimistic about the prospect of using blockchain as a tool in land administration. They observe that there are many avenues through which to implement a blockchain based system, and many questions that must be answered prior to an implementation. In the technical realm, these academics and practitioners debate whether or not the land registry should be placed on a public platform like Bitcoin or a private platform like the one that the Austin-based startup Factom attempted in Honduras. A public blockchain platform would provide “proof of work” checks that enhance immutability of the blockchain, but the transaction costs are high. Public blockchain transactions require 5,000 times more energy than a Visa credit card transaction (Barbieri and Gassen, 2017). This would appear not to be a problem since there might only be a few hundred real estate transaction per day in a given country, but with electricity and energy costs high in developing countries, this is a dissuasive factor. Put another way, a blockchain network that process 300,000 transactions per day would require a similar amount of energy that is consumed in a small country in that same twenty-four-hour period (Vos, 2017). The process that is so time and energy intensive is the “proof of work” process. While proof of work enhances the security and immutability of the system, it requires complicated mathematical computations along with majority consensus algorithms that require a good bit of computing power.

In 2017, when Vos presented his paper at the World Bank Conference on Land and Poverty, the only alternative was a tradeoff between system security and massive amounts of computing power. If one wanted to design a system that required less computing power and therefore less energy, one could utilize a private blockchain or use a different type of consensus mechanism, but this arrangement would provide less system security. A new startup company based in Richardson called Hedera has raised over $120 million dollars as they work to build a “governing council” of a public hashgraph network that would act as a trust layer that sits on top of the internet (Baird et al., 2018). This kind of innovation is exactly what we might expect in a sector as dynamic as blockchain technology. Hedera provides a solution to the energy consumption issue described above by allowing secure transactions at over 500,000 transactions per second (Baird et al., 2018). The author met with Mance Harmon, CEO of Hedera, this fall and he (Mance) is confident that their platform can solve the majority of the issues.

The third strain in the literature consists of academics and practitioners who feel that blockchain applied to land administration is not the right fit. Barbieri and Gassen (2017) are the most critical of the arrangement proposed by blockchain enthusiasts. While they recognize the economic hindrance caused by the face that “of the 7.3 billion people in the world, only two billion have title that is legal and effective,” they are fairly skeptical that blockchain will be the avenue through which these property owners formalize their property holdings (Barbieri and Gassen, 2017). Their primary concern is that a public blockchain network is not secure enough from cyber-attacks, and a private blockchain network, while more secure, forgoes many of the benefits inherent with a distributed ledger that make blockchain attractive in the first place.

Other issues raised by the authors include; seismic shifts in political power, the risk of lost cryptographic keys, re-encryption challenges, energy consumption, and data accumulation issues. These are all valid concerns, but the concerns are no more or less, just different, than the concerns with the current systems in place in many developing countries. The authors are from Germany and therefore are likely thinking of the challenges in reference to the welloiled machine that is German property rights law. With this as the backdrop, it would be logical to give more weight to obstacles because the cost benefit analysis falls short when thinking about a stable OECD country with centuries of property law under its belt. However, when considered in the context of less developed countries, the risks and rewards begin to make more sense. First of all, their concern about seismic political shifts is irrelevant because no cadastre or land management system, blockchain included, can protect against a totalitarian takeover or the predations of a roving bandit to use Mancur Olson’s terminology. If the state is captured by a despot, he can just as easily confiscate the real property of his people whether the property records are listed in a centralized database, on paper, or on a blockchain based ledger.

I question the logic of their concerns about lost cryptographic keys as well. Might it not be equally possible that the government entity responsible for land administration could misplace, damage, or corrupt a file that holds land registry information? At least in the blockchain scenario, the person who has the most interest in the property, the owner, is the one responsible for keeping their cryptographic key in a safe place rather than a bureaucrat with no dog in the fight. Furthermore, it is not as if someone who misplaces their cryptographic key will immediately be evicted from their land. On the contrary, no one else will have the key either and hence there is no way for a false claimant to enter the picture. In a situation where there is not proof of ownership under the current centralized storage system, a false claimant could hire an unscrupulous lawyer to draft a forged document and a legal battle over ownership would ensure (under the best of conditions, under the worst, there would be bloodshed). In the same situation under a blockchain based land registry, a false claimant would have no way to claim ownership since they would not be able to produce the cryptographic key.

The scenario described above heightens the need for strong network security to ensure that keys are not stolen in a hacking attack. This concern has the most merit out of all of their concerns. If 51% of blockchain miners and nodes reach consensus about some data point, then that data is secured into the blockchain as truth (Nakamoto, 2009). Therefore, if one group can amass 51% of the miners and nodes to initiate some nefarious transaction, then the system has been compromised. While it is extremely unlikely that one group could do this since it is in the interest of the other blockchain miners and nodes to maintain a truthful ledger, it is possible. This kind of attack can be prevented on a private blockchain and it has become impossible on a blockchain such as the one that Hedera has developed. The Hedera platform retains the benefits of a public blockchain but has the security of a private blockchain since it is overseen by a distributed council of respected intermediaries. The best analogy I can think of for this is that it is like the difference between direct democracy and the representative sort. Direct democracy is like a normal public blockchain in that it is prone to populism and demagoguery, while representative democracy retains many of the benefits of direct democracy but with more stability.

The last issue that will be addressed from the literature in the “never blockchain” camp is the argument that data accumulation makes blockchain too cumbersome to be used in land registries. It is true that blockchains steadily accumulate data since all of the data must remain as a whole rather than transmission of the limited, pertinent data in a transaction (Barbieri and Gassen, 2017). However, Bitcoin is continuing to operate with a quarter of a million transactions per day at time of writing. The author must be forgiven for thinking that property transactions would take place at a rate of a few hundred per day or, at the most, a few thousand per day in a given country. Another way to ease this problem is to maintain a blockchain based land registry alongside the original centralized land registry database.

The blockchain registry might just contain digital signatures and proof of ownership while the centralized database could contain files that are normally found in cadasters like land use plans, deeds, GIS overlays, regulations issued by the courts and any other overlays needed to complete the picture. This is not as preferable to all of the documents being kept on the blockchain as corrupt officials could change the parcel sizes by altering GIS images or swapping them out for new ones. In order to realize the full effect, all documents must be transferred to the blockchain. Rather than utilize a public blockchain that could suffer from a data accumulation problem, the best solution lies in utilizing a quasi-public blockchain like Hedera. Hedera operates with 100% efficiency in that no block is pruned of the proverbial vine like it is in Bitcoins blockchain. This greatly increased efficiency makes data accumulation a nonfactor since the process of amalgamating blocks requires much less computing power. The main point is that innovate companies are already finding ways to overcome data accumulation challenges, and these solutions will only become more effective in the future.

The case of Texas

The administration of property in the United States, and Texas specifically, is a nuanced affair lacking in uniformity and cohesion. Municipal America is a fragmented puzzle linking over 90,000 local jurisdictions providing the most basic services to American citizens. Texas alone is home to 254 counties plus local jurisdictions of both general and limited authority. The classic fragmented approach leaves each county with the responsibility of administering land. While most counties have a limited budget to embrace land administration innovation, the large number of land administration offices creates opportunities for decentralized experimentation.

Why must Texas municipal leaders pursue land administration innovation and cooperation in the first place? Their world is changing at a rapid pace as Thomas Friedman argues in his book, Thank You for Being Late. Individuals and organizations typically avoid adapting unless change is on the horizon. Municipal America is experiencing trends and challenges that mandate innovation especially in real estate and land administration.

The nature of Texas politics and its governing history challenges government innovation. The state embraces a hybrid of the traditionalist/individualistic political cultures. Most Texans are skeptical of government and public spending at all levels but this may actually favor innovation in the land administration space rather than dissuade from it. Regional cooperation offers one way for counties to keep costs low and benefit from economies of scale in regards to the implementation of a blockchain registry. Counties in larger cities have more incentives to innovate in this way due to higher volumes of real estate transactions and reliance on property tax revenue. In the Dallas/Ft.Worth area, the third largest metropolitan area in the United States, two counties have expressed a willingness to consider a blockchain land registry. The authors conducted meetings with Ellis County elected officials and members of their land administration office to explore a blockchain land registry pilot program in partnership with a blockchain real estate company. While we will keep the name of this company confidential, they offered to conduct the pilot program at no cost and provide the backend technology support to make this project happen. Several weeks into the discussion, political forces derailed the pilot project. It is unclear which level of county government stepped in to end the project, but it appears that someone in authority became aware of the pilot and put an end to it. There have been several other failed pilot projects in the United States, and of course a few successful ones (see Medici and Propy), but from conversations with country officials and blockchain firm representatives, it seems that political factors more often derail pilot projects rather than technical challenges.

Blockchain technology is progressing rapidly and technical barriers to implementing a blockchain registry a falling quickly, but political barriers persist. An informal survey of blockchain land administration officials and country representatives in Texas shed light on this phenomenon.

From this unrepresentative survey, we can see that respondents believed that the land administration offices and title companies would be most resistant to a blockchain land registry. Anecdotal experiences from the authors align with the respondents. This analysis, though, does not travel. There are numerous land administration jurisdictions around the world. While patterns will emerge, each pilot program and implementation will have unique political challenges.

The case of Honduras

The World Bank conducted a comprehensive study titled the Land Administration and Information Systems group. The failed blockchain land registry pilot program in Honduras is further evidence that the political challenges extend across the world. Factom, a respected blockchain company out of Austin, Texas, won a contract to develop a tamper-proof blockchain land title system. Amidst some controversy, Factom CEO Peter Kirby admitted that the project had stalled for “political reasons” (Kirby, 2015). The project was to begin in the city of La Ceiba and expand after the proof-of-concept had been established (Rizzo, 2015). The Honduran Government remained silent about the project throughout. The authors spoke with members of the Factom team about the “political reasons” behind the stall in the project but nothing was ascertained other than the fact that it was clear that friction within the government was at the root. As mentioned in the literature review, around 80% of land held by private individuals in Honduras is either untitled or incorrectly titled (Collindres et al., 2016). To make matters worse, a 2015 audit of the Honduran land titling entity uncovered more than 700 irregularities, most of which were related to “criminal acts of corruption” (Collindres et al., 2016). The system is highly politicized in that elected officials change titles for key supporters or refuse to enforce the titles of political opponents. It is not hard to imagine why this kind of project would create friction amongst the elite in the country. Recognizing the state of the Honduran land registry, the World Bank itself conducted research and initiated a land registry improvement project in Honduras in 2018 with their Land Administration and Information Systems project (Gonzales, 2018). Given the prior experience of World Bank project managers, they are likely to be much more adept at navigating the political hurdles in Honduras than the Factom project managers. Certainly, Factom provides excellent products and services, but perhaps a partnership with the World Bank or other NGO within Honduras would have provided a smoother entry into the world of land management politics.

Conclusion and discussion

In years past, the major concern surrounding blockchain based land registries has been the technical challenges presented by first generation blockchain technology. There were serious concerns about transaction speed, on chain storage capacity, and accessibility in the developing world. With each passing year, these challenges continue to evaporate with modifications and improvements in blockchain technology. However, the underappreciated obstacles to the successful implementation of a blockchain land registry are of a political nature. Control over land administration processes, real estate transaction processes, and generally control over accurate information provide incumbent, rent-seeking firms with lucrative profit opportunities. This paper has argued that the largest obstacle to the adoption of blockchain technology for land administration is undoubtedly in the political sphere.

As can be seen by several failed pilot programs and the informal survey conducted as part of this paper, political obstacles appear to be more of a deterrent than the technical obstacles with the technology. There remain limitations to blockchain technology for the land recorder’s office, but the pace of advancement in this technology demonstrate that these limitations can be overcome by private firms that realize the revenue potential for the company that can sell software applications for the purpose of improving land governance. The good news is that academic are more familiar with analyzing the kinds of principal-agent problems and veto players that characterize the political obstacles to adoption.

Future research must focus on stakeholders, veto players, and mapping economic incentives. If veto players should be given incentives to transition to a more transparent system, then perhaps they can be turned into advocates rather than obstacles. Examples of this may look like title companies running a node on the blockchain network with the ability to more efficiently track the chain of title. While a blockchain land registry negates the need for title insurance in the long run (once enough transactions and reliable data have been logged on the blockchain), in the short and medium term, they can benefit from lower labor costs due to increased transparency and efficiency.

While political obstacles may be more difficult to overcome than the technical, it is important that we understand the main barrier to the adoption of blockchain land registries for the sake of the future flourishing of the jurisdictions that wish to employ them.

References

Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. (2006). Economic Backwardness in Political Perspective. American Political Science Review, 100(1), 115–131. https://doi. org/10.1017/S0003055406062046

Akkermans, B. “Property Law.” Introduction to Law: Second Edition. Springer International Publishing, 2017. 79–108. Web.

Aristotle. (350 B.C.E.) The Politics of Aristotle, translated by E. Barker (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1946). Aristotle, & McKeon, R. (1941). The basic works of Aristotle. New York: Random House.

Baird, L., Harmon, M., and Madsen, P. (2018). Hedera: A Governing Council and Public Hashgraph Network. Whitepaper v.1.4 https://www.hedera. com/hh-whitepaper-v1.4-181017. pdf Accessed 12/3/18.

Barbieri, M. & Gassen, D. (2017). Blockchain: Can this new technology really revolutionize the land registry system? World Bank Conference on Land and Poverty.

Barnes, G., Stanfield, D., & Barthel, K. (1999). LAND REGISTRATION MODERNIZATION IN DEVELOPING ECONOMIES: A DISCUSSION OF THE MAIN PROBLEMS IN CENTRAL/EASTERN EUROPE, LATIN AMERICA, AND THE CARIBBEAN. URISA Annual Conference. Retrieved May 30, 2019, from http://citeseerx. ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi =10.1.1.522.6053&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Baum, A. 2017. “Oxford Future of Real Estate Initiative | Saïd Business School.” https://www.sbs.ox.ac.uk/research/ centres-and-initiatives/oxford-future-realestate- initiative (February 13, 2020).

Besley, Timothy. (1995). “Property Rights and Investment Incentives: Theory and Evidence from Ghana,” Journal of Political Economy 103, no. 5 (Oct., 1995): 903-937.

Besley, T. J., & Burgess, R. (2000, May). Land Reform, Poverty Reduction, and Growth: Evidence from India. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 115(2), 389–430.

Besley, T. and Ghatak, M. (2009) Property rights and economic development. In: D. Rodrik and M. Rosenzweig, eds., Handbook of Development Economics, 1st ed. Elsevier, pp.4525–4595.

Bethell, Tom. (1999). The Noblest Triumph. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Bjørnskov C., Foss N. (2010) Economic Freedom and Entrepreneurial Activity: Some Cross-Country Evidence. In: Freytag A., Thurik R. (eds) Entrepreneurship and Culture. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

Brasselle, A.-S., Gaspart, F. and Platteau, J.-P., (2002) Land tenure security and investment incentives: puzzling evidence from Burkina Faso. Journal of Development Economics, 67(2), pp.373–418

Brasselle, A.-S., Gaspart, F. and Platteau, J.-P., (2002) Land tenure security and investment incentives: puzzling evidence from Burkina Faso. Journal of Development Economics, 67(2), pp.373–418

Casey, Michael and Vigna, Paul. (2018). The Truth Machine: The Blockchain and the Future of Everything. New York: St. Martin’s Press. Casey, Michael. & Vigna, Paul. (2018). The truth machine: the blockchain and the future of everything. New York : St. Martin’s Press Ceyhun Haydaroğlu, The Relationship between Property Rights and Economic Growth: an Analysis of OECD and EU Countries, DANUBE: Law and Economics Review, 6, 4, (2015).

Chavez-Dreyfuss, Gertrude. 2015. “Honduras to Build Land Title Registry Using Bitcoin Technology.” Reuters India. Accessed 13 August 2015. http://in.reuters. com/article/2015/05/15/usa-hondurastechnologyidINKBN0O01V720150515.

Clague, C., Keefer, P., Knack, S. et al. Contract-Intensive Money: Contract Enforcement, Property Rights, and Economic Performance. Journal of Economic Growth (1999) 4: 185. https:// doi.org/10.1023/A:1009854405184

Coit, C. S. (1989). Introduction to real estate law. Chicago: Real Estate Education.

Collindres, J., Regan M., Panting, G. (2016). Using Blockchain to Secure Honduran Land Titles. Fundacion Eleutera.

ConsenSys. 2019. “Deloitte: 80% of Businesses See Blockchain as a Strategic Priority.” Medium. https://media. consensys.net/deloitte-80-of-businessessee- blockchain-as-a-strategic-prioritye8c89cb0a57f (February 13, 2020).

Copeland, Rick. (n.d.). Transitioning to a Strong Sustainable Host Country Economy. U.S. Army Peacekeeping and Stability Operations Institute.

Copeland, Rick. (n.d.). Strategic Imperative for Host Country Economic Capacity Building: “Unity of Understanding.” U.S. Army Peacekeeping and Stability Operations Institute.

Davidson, Sinclair, Primavera De Filippi, and Jason Potts. 2016. “Economics of Blockchain.” In Public Choice Conference, Fort Lauderdale, United States. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/ hal-01382002 (February 14, 2020).

Deininger, K., Augustinus C., Enemark S., and Munro-Faure, P. (2010). Innovation in Land Rights Recognition, Administration, and Governance. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/ The World Bank. Washington, D.C.

Demarest, G. (2009). Property & peace: insurgency, strategy and the statute of frauds. Fort Leavenworth, KS: Foreign Military Studies Office.

DeSoto, H. (2000). The mystery of Capital: Why capitalism triumphs in the West and fails everywhere else. New York: Basic Books.

DeSoto, H. (2013). Thoughts on the Importance of Boundaries. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 157(1), 22-31.

Eckstein, H. (n.d.). Case Study and Theory in Political Science. Case Study Method, 118-164. doi:10.4135/9780857024367.d11

Fenske, J. (2011) Land tenure and investment incentives: Evidence from West Africa. Journal of Development Economics, 95, pp.137–156

Field, E., & Torero, M. (2006). Do property titles increase credit access among the urban poor? Evidence from a nationwide titling program. Harvard University.

Frankenfield, Jake. (2019). “Smart Contracts: What You Need to Know.” Investopedia. https://www. investopedia.com/terms/s/smartcontracts. asp (February 20, 2020).

Gonzalez, Francisco. (2005). Effective Property Rights, Conflict and Growth. Department of Economics, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada T2N 1N4. Received 21 August 2003, Revised 15 July 2005, Available online 7 November 2005.

Gonzalez, Mary Lisbeth. 2018. Honduras – Land Administration and Information Systems Project (English). Washington, D.C. : World Bank Group. http://documents.worldbank. org/curated/en/879981516734844931/ Honduras-Land- Administrationand- Information-Systems-Project

Graglia, J. M., & Mellon, C. (2018). Blockchain and Property in 2018: At the End of the Beginning. Innovations: Technology, Governance, Globalization, 12(1-2), 90-116. doi:10.1162/inov_a_00270

Hanus, P. (2013). Correction of location of boundaries in cadastre modernization process. Geodesy and Cartography, 62(1), 51-65. doi:10.2478/geocart-2013-0003

Haydarolgu, Ceyhun. (2015). The Relationship Between Property Rights and Economic Growth: An Analysis of OECD and EU Countries. Law and Economics Review 6 (4), 217- 239 DOI: 10.1515/danb-2015-0014

Hayek, F. A. (1973). Law, legislation and liberty: A new testament of the liberal principles of justice and political economy. Chicago (Ill.): University of Chicago Press.

Hardin, Garrett. (1968). The Tragedy of the Common. Science, Vol. 162, Issue 3859. pp. 1243-1248. DOI: 10.1126/science.162.3859.1243

Heitger, B. (2004). Property Rights and the Wealth of Nations: A Cross-Country Study. The Cato Journal 23 (3): 381-402.

Henley, Giles. (2013). Property Rights and Development Briefing: Property Rights and Rural Household Welfare. UK Overseas Development Institute (ODI). London, United Kingdom.

Hobbes, T., edited by: Malcolm, N. (2012). Leviathan. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

“IBM Blockchain – Enterprise Blockchain Solutions & Services | IBM.” https://www. ibm.com/blockchain (February 13, 2020).

Kanojia, Sanjay. (2015). Why the Modi Government must work on Land Reform before Land Acquistion. Scroll. in. Accessed December 8, 2018. https:// scroll.in/article/741036/why-the-modigovernment- must-work-on-landreform- before-land-acquisition

Kirby, T. (2015). A Humble Update on the Honduras Title Project. Factom. https://www.factom.com/ uncategorized/a-humble-updateon- the-honduras-title-project/

Kusago, T. (2005). Post-conflict propoor private-sector development: The case of Timor- Leste. Development In Practice, 15(3/4), 502-513. doi:10.1080/09614520500075995.

Larsson, G. 1991. Land Registration and Cadastral Systems. New York: Longman Scientific and Technical. Lemieux, Victoria Louise. (2016) “Trusting records: is Blockchain technology the answer?”, Records Management Journal, Vol. 26 Issue: 2, pp.110-139, https://doi. org/10.1108/RMJ-12-2015-0042

Milgrom, P. R., North, D. C., & Weingast, B. R. (1990). The role of institutions in the revival of trade: The law merchant, private judges, and the champagne pairs. Stanford, CA: , Hoover Institution, Stanford University.

Moyo, Dambisa. (2009) Dead aid :why aid is not working and how there is a better way for Africa. Vancouver : Douglas & Mcintyre, Nakamoto, S. (2009). Bitcoin: A peerto- peer electronic cash system. Accessed 11/24/18. https://bitcoin.org/bitcoin.pdf.

North, D. C., & Thomas, R. P. (2009). The rise of the Western world: A new economic history. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Pr. Olson, M. (2000). Power and Prosperity: Outgrowing Communist and Capitalist Dictatorships. Basic Books. New York, NY.

Olson, M. (1993). Dictatorship, Democracy, and Development. American Political Science Review, 87(3), 567-576. doi:10.2307/2938736.

Olson, M. (1965). The Logic of Collective Action. Harvard University Press. 9780674537514

Ostrom, E. (2003). How Types of Goods and Property Rights Jointly Affect Collective Action. Journal of Theoretical Politics, 15(3), 239-270.

RAND Corporation (2009). Guidebook for Supporting Economic Development in Stability Operations. RAND Corporation. Santa Monica, CA.

Richardson, C. J. (2005). The Loss of Property Rights and The Collapse of Zimbabwe. Cato Journal, 25(3), 541–565.

Ricketts, M. (2005). Poverty, Institutions, and Economics: Hernando DeSoto on Property Rights and Economic Development. Economic Affairs, 25: 49- 51. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0270.2005.00552.x

Rodrik, D. (2004). Getting Institutions Right. CESIFO DICE Report, 2(2), 10–15.

Rodrik, D. (2000) Trade Policy Reform as Institutional Reform in Handbook on “Developing Countries and the Next Round of WTO Negotiations,” edited by Bernard HoekmanSelvetti, C. 2012. Rapid review of the literature on Property Rights – 31 October 2012. DfID

Rizzo, Pete. (2015). Blockchain Land Title Project “Stalls” in Honduras. CoinDesk. https://www.coindesk.com/ debate-factom-land-title-honduras

Scott, B (2016). How Can Cryptocurrency and Blockchain Technology Play a Role in Building Social and Solidarity Finance? United Nations Research Institute for Social Development No. 2016-1.

Smita, Sinha. (2018). How Andhra Pradesh is emerging as India’s blockchain hub. Analytics India. Accessed December 8, 2018. https://www.analyticsindiamag. com/how-andhra-pradesh-is- emergingas- indias-blockchain-hub/

Snall, M. (2017). Blockchain and the Land Register: A New “Trust Machine”? World Bank Conference on Land and Poverty.

Sylwester, K. (2001). A Model of institutional formation within a rent seeking environment. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 44, 169-176.

Teng, J. (2000). Endogenous authoritarian property rights. Journal of Public Economics, 77, 81-95.

Themistocleous, M. (2018). Blockchain Technology and Land Registry. Cyprus Review, 30(2). Retrieved May 30, 2019.

Thompson Reuters Foundation. (2016). Millions of land, property cases stuck in court. Accessed December 8, 2018. https://www.deccanchronicle. com/nation/current-affairs/090816/ millions-of- land-property-casesstuck- in-indian-courts.html

Transparency International. (2009). Global corruption barometer 2009. Berlin: Transparency International.

UN-FIG. (1996). Bogor Declaration on Cadastral Reform. Report from United Nations Interregional Meeting of Experts on the Cadastre, Bogor, Indonesia, 18-22 March, 1996. A joint initiative of the International Federation of Surveyors (FIG) and the United Nations. http://www.sli.unimelb.edu.au/ research/publications/IPW_publ.html.

Vos, J. (2017). Blockchain Based Land Administration: Feasible, Illusory, or a Panacea? World Bank Conference on Land and Poverty. Washington DC, March 20-24, 2017.

Williamson, Enemark, Wallace, and Rajabifard. (2009). Land Administration Systems for Sustainable Development. ESRI Press.

Williamson, P (n.d.). The Evolution of Modern Cadastres. Director, United Nations Liaison, International Federation of Surveyors. The University of Melbourne Victoria, Australia.

The paper was prepared for presentation at the “2020 World Bank Conference on Land and Poverty” The World Bank – Washington DC, March 16-20, 2020.

(7 votes, average: 1.00 out of 5)

(7 votes, average: 1.00 out of 5)

Leave your response!