| Policy | |

Recognising indigenous community rights

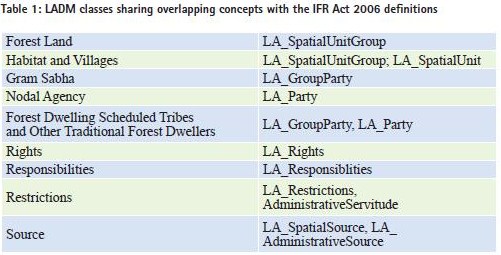

Considering its commitment to highlight the user rights issues, Integrated Spatial Analytics Consultants (ISAC) has teamed up with Portuguese and Dutch academicians to focus in the current paper on the Indian Forest Rights Act from 2006 as the Use Case of indigenous property rights. United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples reaffirmed the importance of the protection of indigenous property rights in Articles 25- 29. This is important to international scale projects such as REDD+ and VCM, as many PES programmes are implemented on customary or indigenous lands over which the land tenure and rights to resources are complex and informal. Historically, India has a large number of forest dwelling tribes or which are largely dependent on forest products for their livelihood. However, after gaining independence, Indian forests became property of the state and thus, the right of residing or traditional collection of forest produce became illegal in many areas designated as reserved or protected forest areas by the government. This denied the forest dwelling tribes and other related tribes their historical rights to earn their livelihood based upon forest produce. Finally, in 2006 through an extraordinary gazette, the Indian government declared Indian Forest Rights Act for recognizing the traditional rights of such tribes to reside in and earn their livelihoods through forests. The background and current situation regarding the forest rights on ancestral lands and their habitat is first examined by literature review, followed by a modelling approach supported on the Land Administration Domain Model. The existing legislation is examined for its land administration aspects and related spatial dimensions with the aim to derive a specialized model applicable to the Indian Forest: IFR_LADM (Land Administration of Indian Forest). Initially, a set of relevant definitions is extracted from the Indian Forest Rights Act, 2006. The following list shows the LADM classes sharing overlapping concepts with the IFR Act 2006 definitions as mentioned in table 1. ISAC highlights spatio-temporal dimensions of the research issues as part of its focus on spatial technologies usage to provide scientific input to policy issues. In the IFR Act, such dimensions are not explained explicitly but some statements could be easily described under this section. This includes: 1. Rights for conversion of leases or grants issued by any local authority or any state government on forest lands to titles. This means land titles to a defined spatial unit. However it does not state the extension of rights in the third dimension i.e. subsurface. 2. Gram Sabha shall be the authority to initiate the process for determining the nature and extent of individual or community forest rights by preparing a map delineating the area of each recommended claim. 3. Right of ownership, access to collect, use and dispose of minor forest produce which has been traditionally collected within or outside village boundaries. This describes the spatial limits of rights related to minor forest produce. It also has a vague time-spec element by referring to traditional collection. 4. Other community rights of uses or entitlements such as fish and other products of water bodies, grazing (both settled or transhumant) and traditional seasonal resource access of nomadic or pastoralist communities. This refers to temporal element in resource access by nomadic or pastoralist communities during particular seasons. 5. The Act empowers the holders of any forest right, Gram Sabha and village level institutions to ensure that adjoining catchments area, water sources and other ecological sensitive areas are adequately protected. This empowerment clearly gives a spatial(2D and 3D) extension to the forest rights of the holders beyond their village or habitat limits. 6. The recognition and vesting of forest rights under this act shall be subject to the condition that mentioned tribes or dwellers had occupied forest land before the 13th day of December, 2005. These spatial dimensions can be extended further in LADM framework. It is not clear and seems to be most unlikely that Forest Rights Act, 2006 allows the holders to raise credit against the entitled individual/community land holdings. This rules out the possibility of working with Case C27 of LADM i.e., Spatial Unit with Micro Credit. However, the formal rights granted to the holders of ownership, access to collect, use and dispose of minor forest produce within or outside village spatial demarcation; community rights or entitlements such as fish and other products of water bodies, grazing etc., can be considered as a basis for raising credit. Slight modification of Case C10 of LADM i.e., Mortgage on Ownership (Formal Rights), considering above mentioned formal rights equivalent to Parcel Ownership rights, will enable credit rising for the right holders. From an initialset of definitions extracted from the Act, a functional, aspect driven approach is followed. Each different aspect is first considered on its own iteration, before producing a comprehensive model where relationships and constraints are identified. To finalize the modelling, a number of Instance Level diagrams is depicted and described, in order to demonstrate the IFR_LADM model’s ability to answer to specific, expected situations on the ground. No Model Driven Architecture (MDA) methods and tools were applied at this first modelling stage in deriving a specialized model for IFR_LADM. The modelling tools offered by Eclipse Modelling framework (EMF) [7] were used to manually derive specialized classes from their respective LADM super-classes [8], by considering, in a first iteration, a total of four packages and functional groupings. These were:

The study of the Act concerning the identification of the participating Actors and their roles in the administration of Indian Forest Land, led to the creation of two specialized classes, one for Group Parties, and other for individual Party elements, having each a dedicated enumeration type, respectively ‘typeIFR’ and ‘roleIFR’. Each one is examined in turn.

For the Administrative package of LADM, and within this first iteration, only the classes from the core class representing Rights, Restrictions and Responsibilities (LA_RRR) were considered for examination. No specialized ‘IFR’ classes were created. The individual hold of forest land is represented by the Property rights, while the shared use for habitation and self-cultivation is represented by the remaining rights of Use & Habitation, Superficies or Usufruct. Those derived rights, however, do not have to be shared and can be held by a single member. Under IFR Source Classes section, the ‘Source’ refers to the LADM specializations from the base LA_Source class, representing any legal or technical documents which support the definition of other model objects, such as Rights, Basic Administration Units or any Surveying documents. According to LADM, one should differentiate between any sources confirming the Nature of the Rights, from those confirming the corresponding Extent where those Rights (or Restrictions or Responsibilities) apply. The section 6, item 1 of the Act is clear about which types of Land Parcels should be defined by the Gram Sabha (and confirmed by the local government): those are the Private Property Rights and those held in Common. Also according to LADM, the Extent or Spatial Source (in IFR_LADM is represented by IFR Forest Rights Extent) belongs to the Surveying sub-package from the Spatial Unit, and is a technical document to be prepared with the participation of Land Surveyors. Although this is not explicit in the Act, it is proposed to include in this procedure the participation of some method of surveying to be validated by credited surveyors, but which can be sufficiently fast and affordable for such communities. Regarding the Administrative Source document, represented in IFR_LADM by the class IFR Forest Rights Nature, should be adapted to the specifics of the Indian Forest and respective Parties, according the flexibility granted by LADM (as a Domain Model). As for the Extent source document, a specific regulation must be prepared, taking into account the specifics of the Forest Land, and with the participation of members designated by the Gram Sabha. Under Spatial Unit Package, a total of three hierarchical groups can be identified. Firstly, at a basic, individual 44 | Coordinates November 2012 level, there are a number of different types of individual Spatial Units. It is considered that the following classes should share a Planar Partition, that is, there should be no overlaps between them (IFR prefix is omitted):

In a sub-Parcel level and to be contained within Forest Land Parcels, there exists Forest Dwelling Units. All these should be considered as specializations from the LA_Spatial Unit class. The Critical Wildlife Habitats not considered being Public Domain can overlap any of the different types in the Planar Partition. From here, several Grouping Levels can be considered, and in the case of the IFR Act, a first hierarchical level should comprise the following classes:

In terms of the object-oriented software development methodology, this procedure corresponds to a ‘flattening’ of the preceding diagrams, where just the more specialized classes in the specialization chain are preserved. Finally, three instances of LADM Use Cases were prepared to depict an individualindigenous right among the overallgroup party rights held by the Gram Sabha; A Forest Land and Village administered by a Gram Sabha Group Party, and finally a CriticalWildlife Habitat with the State as a Party. In the first Use Case, the individual holds a derived right of Superficies over a Forest Land Parcel owned by the Gram Sabha, while it holds another type of derived right over a dwelling unit. Both rights are shared among members of the family or tribe. The holder of the Property Right is in both cases the local community formed by the Gram Sabha. The second Use Case shows the different hierarchy levels amongst the Spatial Units which belong to a Gram Sabha. The higher hierarchy corresponds to the Forest Land, which can include one or more Villages. The third Use Case shows how a State imposed Administrative Servitude can determine the extent of a CriticalWildlife Habitat which can extend over individualor localcommunalparcels of land. The resulting IFR_LADM shows that the underlying Domain Model(LADM) is flexible enough to translate the relation of people to land through rights for specific land use related categories. It can thus facilitate the design of a Land Administration System supporting poor and marginalized groups, like the forest dwellers in India here reported. We recommend conducting new Case Studies for other developing countries (such as Brazilor China) for future research. The temporal aspects deserve further research, as well as cost effective survey methods and administrative procedures. The results obtained for the Indian Forest Rights, at this detailed level, should then be compared to the new Case Studies, which could lead to the identification of widely applicable modelling patterns. References1. REDD+, UN-Redd Programme, Website: http://www.un-redd.org/ AboutREDD/tabid/582/Default.aspx 2. The Voluntary Carbon Market: Status and Potentialto Advance Sustainable Energy Activities Website: www.greenmarkets. org/Downloads/vCarbon.pdf 3. Seeing People Through the Trees: Scaling up Efforts to Advance Rights and Address Poverty, Conflict and Climate Change; 2008; Rights and Resources Initiative Website: www.rightsandresources. org/documents/files/doc_737.pdf 4. David Mitchell, Australia, and Jaap Zevenbergen, Christiaan Lemmen, and Paulvan der Molen (2011). Land Administration Options for Projects Involving Payments for Carbon Sequestration. FIG Working Week 2011; Bridging the Gap between Cultures Marrakech, Morocco 5. The Scheduled Tribes and Other TraditionalForest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act 2006; Extraordinary Gazette of India, No.2 of 2007 6. NationalCommission for Scheduled Tribes, India, Website: http:// ncst.nic.in/index.asp?langid=1; Accessed in October 2011 7. Steinberg D, Budinsky F, Paternostro M, Merks E (2008). EMF: Eclipse Modelling Framework, Second Edition. Addison-Wesley Professional, p. 744. ISBN 978-0-321-33188-5 8. ISO (2011). Draft InternationalStandard ISO/DIS 19152: Geographic Information – Land Administration Domain Model(LADM) 9. KrollP, Kruchten P (2003). The RationalUnified Process made easy: A practitioners guide to the RUP. Addison-Wesley, April2003. ISBN 978-0-321-16609-8 10. Miles R, Hamilton K (2006). Learning UMl2.0. O´Reilly. 11. RICS: RoyalInstitute of Chartered Surveyors – India. Website: http://www.rics.org/india ; Accessed in September 2011 12. Hespanha J, Jardim M, Paasch J, Zevenbergen J (2009). Modelling Legaland Administrative CadastralDomain. Implementation in the Portuguese LegalFramework. The Journalof Comparative Law, Volume 4, Number 1, p. 140-169.

|

(16 votes, average: 1.69 out of 5)

(16 votes, average: 1.69 out of 5)

Leave your response!