| SDI | |

SDI framework

The work of building “Spatial Data Infrastructure” (SDI) is in progress all over the world. There are many challenges: governance, organisational, technical, data sharing, transitional and more. Readers may recall that in Feb 2011 issue we have published the first part of the paper. Here we present the concluding part. |

|

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

Scope of an SDI framework

Best practice implementations needs to reflect experience: with cost effective world leading operational national systems; several generations of change i.e. experience with different models of private sector and public sector collaboration; in creating and extending systems of policy, regulation and governance; of the affects of different governance regimes, cultures and from international programmes. They therefore need to cover:

– Principles, Patterns and Anti-patterns i.e. lessons on what has worked and what to avoid. Arising from multiple generations of systems (reflecting the economic and social development);

– Collaboration models: indicating interfaces between roles and systems (that in different situations will be private sector or public sector);

– Service and components models: which describe the core components and applicable technologies and standards;

– Standards and technologies: including links to international standards and programmes (ISO/TC211, ISO 19115, FOSS4G etc.);

– Regulatory models: based on past success in the effective systems of policy, regulation and governance in national spatial systems operational delivery. Included in this needs to be recognition of different customary and cultural structures and approaches;

– Promulgation, educational and research models (explain, learn, find out): that identify the activities needed to raise awareness, and underpin new training required and provide a framework for research.

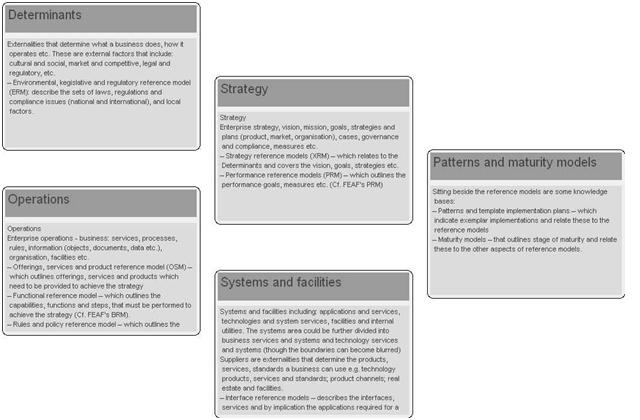

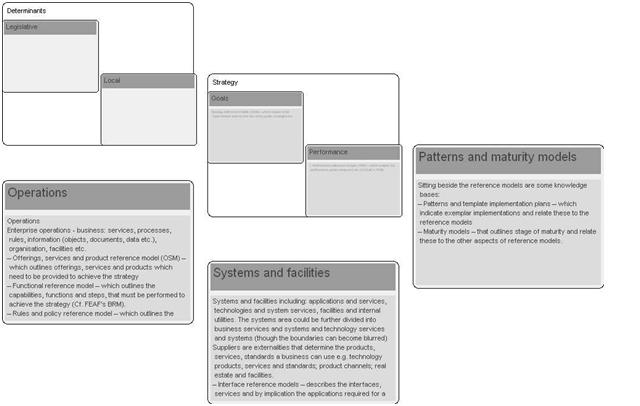

Therefore we propose a set of reference models which capture the fundamental issues

SDI Determinants

– Legislative and regulatory reference model: describe the sets of laws, regulations and compliance issues (national and international).

– Local factors reference model: describes social and cultural factors that influence strategy

NSDI strategy

– Strategy reference models – which relates to the Determinants and covers the vision, goals, strategies etc.

– Performance reference models – which outlines the performance goals, measures etc. (Cf. FEAF’s PRM)

NSDI operations

– Services and product reference model – which outlines the services, products and offerings which need to be provided to achieve the strategy

– Functional reference model – which outlines the capabilities, functions and steps, that must be performed to achieve the strategy (Cf. FEAF’s BRM).

– Rules and policy reference model – which outlines the rules and policies that are required by the strategy and determinants and to support operations.

– Information reference model – which outlines information, metadata and data required by the strategy and determinants and to support operations.

– Organisational reference models – which outlines the organisational units, roles, techniques, skills that are required by the strategy and determinants and to support operations.

NSDI systems and facilities

– Interface reference models – describes the interfaces, services and by implication the applications required for NSDI to operate.

– Technical reference models – describes the technologies, standards required to supports the interfaces.

– Vendor reference model – describes the products, agreements etc. Required

NSDI patterns and maturity models

Sitting beside the reference models are some knowledge bases:

– Patterns and template implementation plans – which indicate exemplar implementations and relate these to the reference models

– Maturity models – that outlines stage of maturity and relate these to the other aspects of reference models.

These reference models are related to allow referential and inferential analysis to be performed. The first three can be considered to represent the requirements and the last two are in the solution domain.

Key characteristics of the SDI framework proposed

We can see a number of other key characteristics we require

– Implementation technology neutral and non-aligned – our NSDI must intrinsically technology and vendor neutral i.e. having no affiliation of alignment, and no preferred SDI technology, products. This allows a clearer focus on the real needs and on standards.

– Accessible by anyone from anywhere – this effectively means Web accessible and is key so that knowledge can accessed where, when and by whom its it required and that knowledge can be capture as a natural by product of field work.

– Supporting different roles, scenarios of use, and levels of control – that is with role based access and presentation, so that people can see what they are interested in in a way that makes sense to them and can change information that is in their domain of control.

– Ensure semantic precision – which ensures it may be analysed with efficiency, fully auditable, that the basis of decisions is explicit, objective and transparent. The lack semantic precision is one of the key problems with most documents.

– Represent idealised models of NSDI – that has a holistic, coherent and complete set of well-structured, unambiguous and well partitioned and categorised set of business definitions (roles, functions, interfaces etc.). Has an explicit conceptual model of how the NSDI organisations are structured and operate (e.g. reporting, controls, data flows etc.)

– Divides the generic framework from the country specific implementation – so the generic framework is reusable and extensible. Allows nations to maintain their know how i.e. how they do things, why they do things – rather than this knowledge be in the hands of third parties with vested interests e.g. consultants, vendors.

– Allows relationships and concepts to be – visualised, analysed and reported on (in SDI we all know that a visualisation can tell convey information in a powerful way).

– As simple as possible – to reduce complexity we limit connections within each level and between each touching levels.

–~~~~~~~~~~~~–

Roles boundaries and flows

Natural Boundaries around Responsibilities

An operationally effective NSDI is contributed to by meeting the key challenges in developing an inclusive model of governance and effective data sharing.

Our themes are that public and private certainly share the task of establishing efficient, operational NSDI and new governance mechanisms are needed to get us there.

The boundaries around the responsibilities need to be drawn and re-drawn. Reorganised government agencies are necessary and relatively simple, being ultimately single legal entities, but sufficient change also requires private sector engagement. So the reorganisation of responsibility is not so simple.

The Spatially Enabled Government in Victoria Australia including [SEG,2007] and the work of the Australian Office of Spatial Data Management (OSDM) suggests “there is general acknowledgement that the major challenges in implementing an enabling platform are not technical, but institutional, legal and administrative in nature.”

They [SEG, 2007] identifies three strategic challenges: governance, data sharing and access and an overarching challenge regarding how to develop a SDI that will provide an enabling platform in a transparent manner that will serve the majority of society. It also suggest SDI development has often been “dominated by the concerns of central governments usually without the participation of stakeholders from the sub national levels of government, the private sector and academia” and oriented at “professional elite rather the population as a whole who are the main beneficiaries”. They suggest an SDI includes “enabling platform linking those who produce, provide and add value to data”.

SEG reference many aspects of an NSDI: organisations, roles and relationships; data, technology and standards; processes, actions and practices; policies and decisions; criteria, business goals, strategies, products and services, laws and regulations.

We see our work building upon past results by facilitating the strategic challenges related to inclusive models of governance for NSDI establishment. What we propose is both a renewed focus on the definition of the responsibility boundaries and a supporting framework to articulate, visualise and analyse the information and knowledge flows.

SEG suggested that “a new business paradigm [promoting] the partnership of spatial information organisations (public/private) to provide access to a wider scope of data and services, of size and complexity that is beyond their individual capacity.” There are recognitions in the SEG work also that we need something above the detail instance and implementation specific data that we commonly find referred to by technical specialists.

Public and private roles

When considering an NSDI we have to balance two opposing flows i.e.of control and of data

– Top to bottom – control and governance naturally flows from top to bottom

– Bottom to top – data naturally flows from bottom to top.

Our implementation mediates between these flows. The state plays a pivotal role in the sound initial establishment of new key national infrastructures e.g. post, telephony, power, broadcasting, road and rail. As approaches to national developments mature we see individuals, the state and private sectors organisations increasingly share these roles and responsibilities (as we have in the other areas of national infrastructure). NSDI is a new class of ‘data’ infrastructure. It enables efficient economies and supports the nation’s socio-economic development objectives and policies.

The challenge for many years, including those when paper based maps, plans, designs and specialised dedicated models suited to a single audience or purpose were common, has been to integrate, maintain, analyse, and enable access by a wide range of different parties.

Individuals, state and private sector organisations share the mandate and responsibility for their establishment and operation. The framework proposed provides a means for dealing with the information about these things (meta-information) that enable governance. SEG suggests a broad goal for an NSDI is to support “more effective and more transparent coordination”. The framework approach here, in the first place allows an effective and transparent co-ordination of the meta-information so that the professional elite and all other stakeholders are able to participate. In this way the framework relates to the flexible setting of public/private responsibility boundaries.

The implementation of complex IT infrastructures (e.g. NSDI), with governance, stakeholders, business users, designers, engineers and planners is assisted by inclusive, early, persistent engagement on responsibilities. Frameworks that enable visualisation of the meta information (functions, meta-data, roles, assets, networks of related elements, …) allow the overall picture to be worked with to suit the needs of the entire constituency.

We want to be able to understand how a number of parties can collaborate in an NSDI. To map the roles, functions, assets, data etc. of these entities we need a framework which is a canonical model. If we wish to be able safely encourage the private sector to engage in some areas we need to very clearly understand the upstream and downstream implications e.g. from a function upstream to what regulations or goals it is critical to from the NSDI perspective and not merely the perspective of an implementing party. The down stream flows are to what technologies and assets are interrelated.

Such an understanding is fundamental to knowledge of gaps, overlaps, risks and impacts of a set of organisations engaging collaboratively to implement, operate and evolve an NSDI.

Engaging the private sector

In the agreements needed on responsibility boundaries a flexible approach contributes success. Agreement and definition of NSDI would be shared, state undoubtedly have the mandate for governance and private are the likely location of efficient implementation and operation.

“Government has to be a smart buyer, meaning knowing what to buy, deciding from whom to buy it, and then determining what it has bought; that is, preparing careful specifications as what is to be purchased, conducting a competitive procurement in a competitive market, and monitoring the contractor’s performance.” (Ref Kettl 1993)

Strong commitment from the top is needed to build the capacity for effective contracting and procurement because of the complexity and challenges of public contract management. (Ref Savas)

NSDI, being relatively new national infrastructures as well as complex systems are ideal programmes to which past lessons on responsibility setting be applied. Hernando de Soto himself illustrates this opportunity. “In many countries, years of state regulatory intervention have produced bureaucratic obstacles and economic stagnation. Hernando de Soto illustrates how much time is wasted in Peru following the labyrinthine official procedures to start a business or build a house: It takes 289 days to register an industrial enterprise and 26 months to license informal taxi operators, for example. The informal economy (i.e., ‘black market’) encourages far greater productivity than the official sector.” (HDS Ref 1989) He advocates deregulation, de-bureaucratisation, and decentralisation.

State and private engagement is necessary for delivery of NSDI. New mechanisms for governance are required for NSDI implementations to work. Engagement between state and private sector should aim to achieve economic efficiency through exposure to market discipline. The emergence of demand-driven, market-based arrangements can be sued to satisfy new needs associated with NSDI.

While privatisation can indeed be mismanaged in these ways, management of ordinary public services suffers from many of these same shortcomings; that is, poor management can sometimes be found whether government is managing public employees or the privatisation process. When mismanagement occurs in the private sector, market forces tend to weed it out ruthlessly. Privatisation and public-private partnerships reflect market principles and together constitute a strategy for improving public management.

Conclusions

We seek to make a non-incremental step in the way that NSDIs are implemented.

We believe that an NSDI requires a framework with specific characteristics, capabilities and structure in order to allow best practice to be capture and applied. It is only by establishing this that we will significantly affect the efficacy of NSDI implementations. Assuring implementation schedules, operational effectiveness and fit for purpose.

Many best practice methods have been identified that we can learn from and we believe there are better ways now available to implement a framework to assure NSDIs to operate effectively.

At present many parties are focused on capturing knowledge that should reside in such a framework. Sadly much of the knowledge still resides in documents or in people’s heads where it is not particularly useful in regard to accessibility, capacity to be integrated and analysed.

Individuals, state and private sector organisations share the mandate and responsibility for NSDI establishment and operation. The strategic challenges related to the inclusiveness of the governance models and inherent approaches to data access, renewal and use.

What we propose is both a renewed focus on the definition of the responsibilities associated with NSDI establishment and a supporting framework to articulate, visualise and analyse the information and knowledge flows.

References

– Alexander, C (1977). A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction. Oxford University Press; ISBN 0195019199.

– CMMI – www.sei.cmu.edu/cmmi/

– COBIT – www.isaca.org

– DODAF – www.defenselink.mil/cio-nii/docs/DoDAF_Volume_I.pdf

– DSM – www.dsmweb.org/

– FEAF – www.whitehouse.gov/omb/e-gov/fea

– Gideon Project, 2008, Key geo-information facility for the Netherlands, Approach and implementation strategy, Netherlands GI Council

– Gruen, N. Dr, Chair, State of Victoria, Australia, Government 2.0 Taskforce (Aug 2009)

– Henderson-Sellers, B. et al., 1999, “Instantiating the Process Metamodel,” JOOP, 12(3): 51-57, (June 1999)

– IFW – www.evernden.net/content/ifw.htm

– ITIL – www.itil-officialsite.com/ .

– Kettl, D.; 1993, Sharing Power: Public Governance and Private Markets (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution), chapter 8

– Lundy, K (2009). Three pillars of Open Government

– SEG – Masser I., Rajabifard A. and Williamson, I.; Spatially Enabling Governments through SDI implementation; Centre for Spatial Data Infrastructures and Land Administration; Department of Geomatics, University of Melbourne,Victoria 3010, Australia; (July 2007).

– The Royal Academy of Engineering (2004), The Challenges of Complex IT Projects, Published by The Royal Academy of Engineering, London; ISBN 1-903496-15-2

– TOGAF – www.opengroup.org/togaf/

– ValIT – www.isaca.org/Content/ContentGroups/Val_IT1/Val_IT.htm

– Zachman – www.zifa.com/

My Coordinates |

EDITORIAL |

|

His Coordinates |

Vice Admiral B R Rao |

|

Mark your calendar |

MARCH 2011 TO AUGUST 2011 |

|

News |

INDUSTRY | LBS | GPS | GIS | REMOTE SENSING | GALILEO UPDATE |

Pages: 1 2

(38 votes, average: 1.05 out of 5)

(38 votes, average: 1.05 out of 5)

Leave your response!