| GNSS | |

GNSS Constellation Specific Monthly Analysis Summary: November 2025

The analysis performed in this report is solely his work and own opinion. State Program: U.S.A (G); EU (E); China (C) “Only MEO- SECM satellites”; Russia (R); Japan (J); India (I) |

|

|

Introduction

This article continues the monthly performance analysis of the GNSS constellation. Readers are encouraged to refer to previous issues for foundational discussions and earlier results. In addition, there is a short overview on the importance of the Earth’s magnetic field for satellite technologies. This is a continuation of the section F from October issue, 2024.

Analyzed Parameters for October 2025

(Dhital et. al, 2024) provides a brief overview of the necessity and applicability of monitoring the satellite clock and orbit parameters.

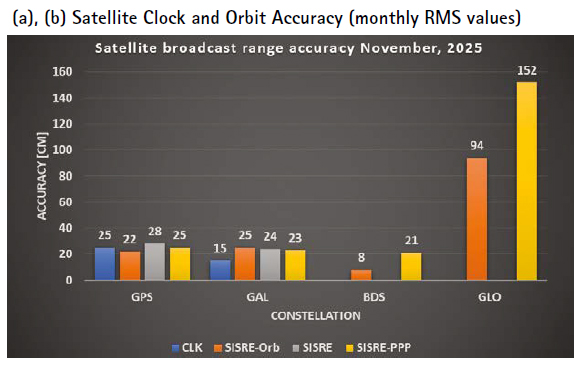

a..Satellite Broadcast Accuracy, measured in terms of Signal-In Space Range Error (SISRE) (Montenbruck et. al, 2010).

b. SISRE-Orbit (only orbit impact on the range error), SISRE (both orbit and clock impact), and SISRE-PPP (as seen by the users of carrier phase signals, where the ambiguities absorb the unmodelled biases related to satellite clock and orbit estimations. Satellite specific clock bias is removed) (Hauschlid et.al, 2020).

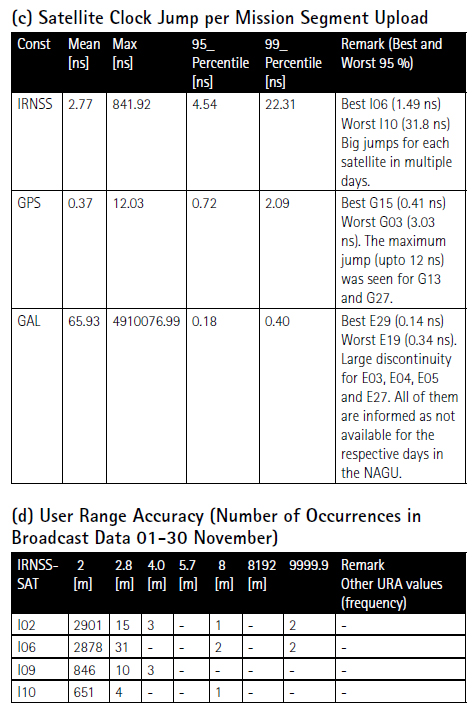

c. Clock Discontinuity: The jump in the satellite clock offset between two consecutive batches of data uploads from the ground mission segment. It is indicative of the quality of the satellite atomic clock and associated clock model.

d. URA: User Range Accuracy as an indicator of the confidence on the accuracy of satellite ephemeris. It is mostly used in the integrity computation of RAIM.

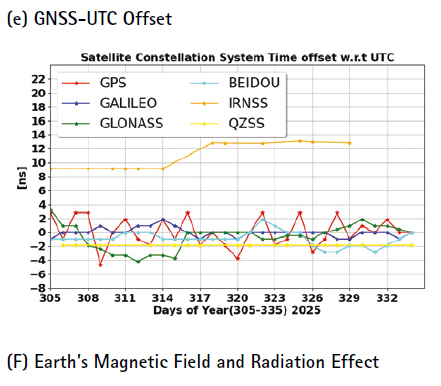

e. GNSS-UTC offset: It shows stability of the timekeeping of each constellation w.r.t the UTC.

f. Earth’s Magnetic Field and Radiation Effect: : The field acts as a vital shield, deflecting charged particles from the solar wind and cosmic radiation that would otherwise bombard the atmosphere and surface.

Note:-for India’s IRNSS there are no precise satellite clocks and orbits as they broadcast only 1 frequency which does not allow the dual frequency combination required in precise clock and orbit estimation; as such, only URA and Clock Discontinuity is analyzed.

The Earth’s magnetic field originates deep within the planet, where molten iron in the outer core moves in vast, turbulent currents. These motions generate electric currents that power the geodynamo, producing a magnetic field that extends far into space. More than just a scientific curiosity, this field acts as a vital shield, deflecting charged particles from the solar wind and cosmic radiation that would otherwise bombard the atmosphere and surface. Although often simplified as a dipole aligned with Earth’s rotation axis, the field is far more complex: its strength and orientation vary across different regions, and it evolves continuously over time. This dynamic nature makes the magnetic field both a subject of geophysical study and a critical factor in protecting satellites and modern technology. The importance of this shielding is underscored by recent aviation incidents, such as the Airbus flight where a cosmic ray caused a bit flip in onboard electronics, reminding us that radiation can disrupt systems even at aircraft cruising altitudes.

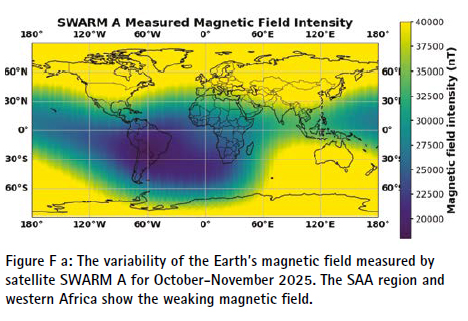

To measure the magnetic field with precision, ESA launched the Swarm constellation in 2013. Each Swarm satellite carries both vector magnetometers, which record the direction of the field, and absolute scalar magnetometers, which measure its intensity. Together, these instruments provide highresolution data on the field’s magnitude and orientation, allowing scientists to compare observations with geomagnetic models such as CHAOS and IGRF. This comparison reveals how the field evolves, highlights anomalies, and helps track the longterm weakening of certain regions.

One of the most striking anomalies is the South Atlantic Anomaly (SAA), a region over South America and the South Atlantic where the magnetic field is unusually weak. The anomaly arises because Earth’s magnetic dipole is offset from the planet’s center and because reversed flux patches exist at the core–mantle boundary. As a result, the field intensity at satellite altitudes can drop below 22,000 nanotesla, far weaker than elsewhere. This weakening allows the inner Van Allen radiation belt to dip closer to Earth, exposing satellites to higher radiation flux. A global magnetic field map, as in Figure Fa computed with SWARM A data from ESA database, vividly illustrates this weakened region, showing how the SAA stands out as a hotspot of vulnerability.

The consequences for satellite infrastructure are significant. Electronics such as chips and memory systems are particularly sensitive to radiation. In the SAA, satellites experience Single Event Effects (SEE), including bit flips, latchups, and memory loss. ESA’s Swarm mission has recorded frequent singleevent upsets in onboard memory during anomaly crossings, confirming the operational risks. GNSS systems are also affected: radiation and plasma irregularities can cause temporary loss of GPS lock, degraded tracking, and increased noise. Swarm’s GPS receivers have documented such disruptions, though they are typically shortlived and corrected in postprocessing.

Oscillators and frequency generators, which provide the timing backbone for satellite payloads, are another critical vulnerability. UltraStable Oscillators (USOs) are designed to deliver precise frequency references, but radiation in the SAA perturbs their stability. This leads to frequency drift and degraded orbit determination. Sentinel3A and Sentinel6A missions, operating at higher altitudes, have reported USO frequency anomalies correlated with SAA crossings. These findings echo earlier GNSS constellation analysis (Section F, October Issue, 2024), where clock oscillations were shown to impact navigation performance. The SAA provides a physical driver for such oscillations: radiation exposure perturbs oscillator stability, which in turn affects GNSS timing and positioning.

In summary, the Earth’s magnetic field is both a scientific phenomenon and a critical infrastructure shield. Its weakening in the South Atlantic Anomaly exposes satellites to radiation that impacts electronics, GNSS receivers, and oscillators. Swarm’s measurements provide the scientific foundation for understanding these changes, while Sentinel’s oscillator anomalies demonstrate the operational consequences. Together, they highlight the importance of monitoring the magnetic field not only for geophysical insight but also for the resilience of satellite technology.

Further readings:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/ article/abs/pii/S0273117718302941

https://www.esa.int/Enabling_Support/ Space_Engineering_Technology/Swarm_ vs._space_radiation_the_first_10_years?

https://mycoordinates.org/gnssconstellation-specific-monthlyanalysis-summary-october-2024/

Monthly Performance Remarks:

1. Satellite Clock and Orbit Accuracy:

• The performance of GPS, Galileo and Beidou remained similar.

• Not much jumps in GPS satellite clocks. Galileo satellites had couple of discontinuities that were covered by NAGUs (unavailability of the satellites)

2. The UTC Prediction (GNSS-UTC):

• IRNS provided comparatively worse performances. Other constellations show consistent and stable predictions.

References

Alonso M, Sanz J, Juan J, Garcia, A, Casado G (2020) Galileo Broadcast Ephemeris and Clock Errors Analysis: 1 January 2017 to 31 July 2020, MDPI

Alonso M (2022) Galileo Broadcast Ephemeris and Clock Errors, and Observed Fault Probabilities for ARAIM, Ph.D Thesis, UPC

Bento, M (2013) Development and Validation of an IMU/GPS/Galileo Integration Navigation System for UAV, PhD Thesis, UniBW.

BIMP (2024 a) https://e-learning.bipm. org/pluginfile.php/6722/mod_label/ intro/User_manual_cggtts_analyser. pdf?time=1709905608656

BIMP (2024 b) https://e-learning. bipm.org/mod/folder/view. php?id=1156&forceview=1

BIMP (2024 c) https://cggtts analyser.streamlit.app

Bruggemann, Troy & Greer, Duncan & Walker, R.. (2011). GPS fault detection with IMU and aircraft dynamics. IEEE Transactions on Aerospace and Electronic Systems – IEEE TRANS AEROSP ELECTRON SY. 47. 305-316. 10.1109/TAES.2011.5705677.

Cao X, Zhang S, Kuang K, Liu T (2018) The impact of eclipsing GNSS satellites on the precise point positioning, Remote Sensing 10(1):94

Chen, K., Chang, G. & Chen, C (2021) GINav: a MATLAB-based software for the data processing and analysis of a GNSS/IMU integrated navigation system. GPS Solut 25, 108. https:// doi.org/10.1007/s10291-021-01144-9

Curran, James T. & Broumendan, Ali. (2017). On the use of Low-Cost IMUs for GNSS Spoofing Detection in Vehicular Applications.

Dhital N (2024) GNSS constellation specific monthly analysis summary, Coordinates, Vol XX, Issue 1, 2, 3, 4

Dhital N (2025) GNSS constellation specific monthly analysis summary, Coordinates, Vol XXI, Issue 1

GINAv (2025). https://geodesy.noaa. gov/gps-toolbox/GINav.shtml

Goercke, L (2017) GNSS-denied navigation of fixed-wing aircraft using low-cost sensors and aerodynamic motion models, PhD Thesis, TUM.

GROOPS (2025) GROOPS Documentation and Cookbook. https://groops-devs. github.io/groops/html/index.html

GSC (2023) Galileo Q3 Performance Report. https://www.gsc-europa.eu/sites/default/ files/sites/all/files/Galileo-OS-Quarterly- Performance_Report-Q3-2023.pdf

Guo, Jing & Chen, Guo & Zhao, Qile & Liu, Jingnan & Liu, Xianglin. (2017). Comparison of solar radiation pressure models for BDS IGSO and MEO satellites with emphasis on improving orbit quality. GPS Solutions. 21. 10.1007/s10291-016-0540-2.

Guo F, Zhang X, Wang J (2015) Timing group delay and differential code bias corrections for BeiDou positioning, J Geod,

Hauschlid A, Montenbruck O (2020) Precise real-time navigation of LEO satellites using GNSS broadcast ephemerides, ION

IERS C04 (2024) https://hpiers.obspm.fr/ iers/eop/eopc04/eopc04.1962-now

IGS (2019) GNSS Attitude Quaternions Exchange using ORBEX

IGS (2021) RINEX Version 4.00 https://files.igs.org/pub/data/ format/rinex_4.00.pdf

InsideGNSS (2024) Working papers: upgrading galileohttps://insidegnss.com/ working-papers-upgrading-galileo/

Jiabo G, Xingyu Z, Yan C, Mingyuan Z (2021) Precision Analysis on Reduced-Dynamic Orbit Determination of GRACE-FO Satellite with Ambiguity Resolution, Journal of Geodesy and Geodynamics (http://www. jgg09.com/EN/Y2021/V41/I11/1127)

Kj, Nirmal & Sreejith, A. & Mathew, Joice & Sarpotdar, Mayuresh & Suresh, Ambily & Prakash, Ajin & Safonova, Margarita & Murthy, Jayant. (2016). Noise modeling and analysis of an IMU-based attitude sensor: improvement of performance by filtering and sensor fusion. 99126W. 10.1117/12.2234255.

Li M, Wang Y, Li W (2023) performance evaluation of real-time orbit determination for LUTAN-01B satellite using broadcast earth orientation parameters and multi GNSS combination, GPS Solutions, Vol 28, article number 52

Li W, Chen G (2023) Evaluation of GPS and BDS-3 broadcast earth rotation parameters: a contribution to the ephemeris rotation error Montenbruck

Liu, Yue & Liu, Fei & Gao, Yang & Zhao, Lin. (2018). Implementation and Analysis of Tightly Coupled Global Navigation Satellite System Precise Point Positioning/Inertial Navigation System (GNSS PPP/IMU) with IMUufficient Satellites for Land Vehicle Navigation. Sensors. 18. 4305. 10.3390/s18124305.

Mayer-Guerr, T., Behzadpour, S., Eicker, A., Ellmer, M., Koch, B., Krauss, S., Pock, C., Rieser, D., Strasser, S., Suesser Rechberger, B., Zehentner, N., Kvas, A. (2021). GROOPS: A software toolkit for gravity field recovery and GNSS processing. Computers & Geosciences, 104864. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.cageo.2021.104864

Montenbruck O, Steigenberger P, Hauschlid A (2014) Broadcast versus precise ephemerides: a multi-GNSS perspective, GPS Solutions

Liu T, Chen H, Jiang Weiping (2022) Assessing the exchanging satellite attitude quaternions from CNES/CLS and their application in the deep eclipse season, GPS Solutions 26(1

Montenbruck O, Steigenberger P (2024) The 2024 GPS accuracy improvement initiatives, GPS Solutions

Montenbruck O, Steigenberger P, Hauschlid A (2014) Broadcast versus precise ephemerides: a multi-GNSS perspective, GPS Solutions

Montenbruck O, Hauschlid A (2014 a) Differential Code Bias Estimation using Multi-GNSS Observations and Global Ionosphere Maps, ION

Montenbruck, O., Schmid, R., Mercier, F., Steigenberger, P., Noll, C., Fatkulin, R., Kogure, S. & Ganeshan, A.S. (2015) GNSS satellite geometry and attitude models. Advances in Space Research 56(6), 1015 1029. DOI: 10.1016/j.asr.2015.06.019

Niu, Z.; Li, G.; Guo, F.; Shuai, Q.; Zhu, B (2022) An Algorithm to Assist the Robust Filter for Tightly Coupled RTK/IMU Navigation System. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2449. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14102449

Schmidt, G, Phillips, R (2010) IMU/ GPS Integration Architecture Performance Comparisons. NATO.

Steigenberger P, Montenbruck O, Bradke M, Ramatschi M (2022) Evaluation of earth rotation parameters from modernized GNSS navigation messages, GPS Solutions 26(2)

Strasser S (2022) Reprocessing Multiple GNSS Constellations and a Global Station Network from 1994 to 2020 with the Raw Observation Approach, PhD Thesis, Graz University of Technology

Suvorkin, V., Garcia-Fernandez, M., González-Casado, G., Li, M., & Rovira-Garcia, A. (2024). Assessment of Noise of MEMS IMU Sensors of Different Grades for GNSS/IMU Navigation. Sensors, 24(6), 1953. https:// doi.org/10.3390/s24061953

Sylvain L, Banville S, Geng J, Strasser S (2021) Exchanging satellite attitude quaternions for improved GNSS data processing consistency, Vol 68, Issue 6, pages 2441-2452

Tanil, Cagatay & Khanafseh, Samer & Pervan, Boris. (2016). An IMU Monitor agaIMUt GNSS Spoofing Attacks during GBAS and SBAS-assisted Aircraft Landing Approaches. 10.33012/2016.14779.

Walter T, Blanch J, Gunning K (2019) Standards for ARAIM ISM Data Analysis, ION

Wang, C & Jan, S (2025). Performance Analysis of MADOCA-Enhanced Tightly Coupled PPP/ IMU. NAVIGATION: Journal of the IMUtitute of Navigation March 2025, 72 (1) navi.678; DOI: https://doi.org/10.33012/navi.678

Wang N, Li Z, Montenbruck O, Tang C (2019) Quality assessment of GPS, Galileo and BeiDou-2/3 satellite broadcast group delays, Advances in Space Research

Wang J, Huang S, Lia C (2014) Time and Frequency Transfer System Using GNSS Receiver, Asia Pacific Radio Science, Vol 49, Issue 12

https://cggtts-analyser.streamlit.app

Yang N, Xu A, Xu Z, Xu Y, Tang L, Li J, Zhu H (2025) Effect of WHU/GFZ/CODE satellite attitude quaternion products on the GNSS kinematic PPP during the eclipse season, Advances in Space Research, Volume 75, Issue 1,

Yao J, Lombardi M, Novick A, Patla B, Sherman J, Zhang V (2016) The effects of the January 2016 UTC offset anomaly on GPS-controlled clocks monitored at NIST. https:// tf.nist.gov/general/pdf/2886.pdf

Note: References in this list might also include references provided to previous issues.

Data sources and Tools:

https://cddis.nasa.gov (Daily BRDC); http://ftp.aiub. unibe.ch/CODE_MGEX/CODE/ (Precise Products); BKG “SSRC00BKG” stream; IERS C04 ERP files

(The monitoring is based on following signals- GPS: LNAV, GAL: FNAV, BDS: CNAV-1, QZSS:LNAV IRNSS:LNAV GLO:LNAV (FDMA))

Time Transfer Through GNSS Pseudorange Measurements: https://e-learning.bipm.org/login/index.php

Allan Tools, https://pypi.org/project/AllanTools/

gLAB GNSS, https://gage.upc.edu/en/learning materials/software-tools/glab-tool-suite.

(1 votes, average: 5.00 out of 5)

(1 votes, average: 5.00 out of 5)

Leave your response!