| Mapping | |

Future national geospatial agencies: contributing to the society and the SDGs

The paper illustrates how geospatial information supports the delivery of SDGs, and demonstrates some of the key national changes that will enable this to occur |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

‘Geospatial is like a general-purpose technology; it’s the oil for the next generation of the digital economy.’ Nigel Clifford, CEO Ordnance Survey, opening the quadrennial Cambridge Conference, Oxford University, July 2017

Globally the geospatial community continues to transform as the world increasingly uses location to unlock value. Disruption sees new ideas, new providers, often bypassing the traditional surveying and mapping authority. The mantra ‘evolve or die’ has never held so true to national mapping and geospatial authorities (NMGA) everywhere. But it is also a time of great opportunity for national mapping agencies to become national geospatial agencies, actively helping to drive the social-economic benefits that good data can help bring.

Why is data important to development and SDGs?

The 2017 World Bank Land and Poverty conference, (Kedar, J, 2017), provided insight into the many and varied socioeconomic benefits GI can bring a nation. It reflected that economic and societal benefits of geospatial enablement are well documented in high-income nations but not in low and middle-income nations.

Quality statistics are accepted as the tool to measurement of progress in implementing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG). Geospatial data contributes too, and it is the integration of such datasets that can add real value. Take the measurement of SDG Tier II Indicator 11.2.1 ‘Proportion of population that has convenient access to public transport, by sex, age and persons with disabilities’.

In some cases, such as Tier 1 Indicator 15.1.1, Forest area as a proportion of total land area, GIS analysis on a range of spatial datasets can provide measurement without recourse to further statistical collections. Clearly, to be of use internationally, there must be common global standards defining forest, data must have the right attributes, be accessible and be of sufficient quality, currency and in the case of SDGs, national coverage. Some Indicators will take more complex geospatial analysis, for example Indicator 6.1.1, Proportion of population using safely managed drinking water services. Here, factors such as natural and artificial barriers to access such as fences, land ownership and control, consistency in supply all are relevant factors. It becomes evident that not only is better data required by analysts, but greater skill and understanding of the decisions being taken from the analysis.

Measurement is one benefit of integrating good GI. In the same three indicators described above, decision makers can use the same data to understand the current situation, plan efficient mitigation, and make investment decisions and commission projects. Contractors then deliver the mitigation, working with the same data, and measurement of progress maintained. In other words, the utility of GI supports the delivery of SDGs, not just measurement. In some nations, the most complete national coverage data about a national infrastructure is still the 1970/80’s UK Directorate of Overseas Survey’s 1:50,000 scale paper map, which may have subsequently been digitized. Projects have collected data additionally, particularly around addresses, administrative boundaries, water sources and roads, and thus the concept of a national spatial data infrastructure holds good. But the trusted fundamental geospatial data is lacking and GI benefits are not being realized.

Illustrating the benefits of GI to SDG delivery

This paper draws upon examples to demonstrate how geospatial capabilities have a real part to play in SDGs. They are not comprehensive examples but do demonstrate the reach across SDGs.

Goals 1 and 10:

United Republic of Tanzania

Urban Development: More than 70% of urban settlements are unplanned. About 1.5 million land parcels are surveyed, 900,000 are allocated and 650,000 are registered. Rural Land Use: Only about 10% of villages have land use plans.

Action is happening: ILMIS, Land Investment Unit, large farm inventory, review of national land policy, increased surveying of land parcels in rural areas.

Security of land tenure is a key enabler. Land is 75% of the value of world’s gross domestic product. Land administration requires effective geospatial data management and provides access to credit and tenure security, enables effective infrastructure planning and delivery, fair compensation and land taxation.

Goals 3 and 10

Responding to fire, serious illness and accident. Time saves lives and money. In Ireland, for example, a navigation device and geospatial data enhances the response time by 17% and reduce cardiac arrest deaths by 10%.

Goals 2, 12, 14 and 14

Rural development. Support through agricultural cadastre, calculation of farming subsidies or compensation payments, irrigation and drainage planning and maintenance, land use planning, getting produce to market, environmental protection and largescale agricultural investments.

Goals 10 and 12

Taxation and government revenue generation. This includes property tax, agricultural land tax, business and income tax

Arusha Local Government Revenues (McCluskey, W, 2017)

As part of World Bank and DANIDA supported Tanzania Strategic Cities Project (TSCP) Arusha has introduced a Local Government Revenue Collection Information System. Over four years from 2013 revenues have more than doubled. These revenues are from sources such as: service levy, property tax, billboards, parking fees, income from sale or rent, market fees and charges, secondary school fee, licenses and permits on business activities and hotel levies.

A key element of this success has been the ability to geographically locate all taxpayers and properties. This has required a comprehensive spatial database: satellite imagery, roads and individual buildings digitised, unique property reference number, attributes (e.g. use, condition, age).

This database could provide a wide range of benefits to other departments, agencies and businesses when shared.

Goals 2, 4, 4, 6 and 9.

National infrastructure development benefits from integrated planning, and integrating data. Benefits include the ability to better manage and optimise existing infrastructure assets, increase efficiency and maintain integrated planning.

Burkina Faso (Ouiba, Y, 2011)

In Ouagadougou, a pilot project has been implemented to reduce water losses within the distribution system of the municipal utility.

The programme has generated positive benefits for the local economy. Local jobs have been created, public health improved, and water efficiency had been increased.

For the case of Ouagadougou, the direct savings of the water loss programme has been estimated to be around 0.8 EUR/m³. With the surplus costs on top, the total economic profit might well exceed 2.0 EUR/m³.

Goal 11

Urban planning and resilient cities. In Tanzania more than 70% of urban settlements are unplanned. Planning for tomorrow requires a comprehensive understanding of today. Dar es Salaam is expected to grow by 85% by 2025. As cities become larger, urban planning and managing the urban environment becomes more complex. The use of geospatial data not only leads to integrated city development but enables planning across power, water, and waste, and improves resilience planning & disaster response, environmental management, transport planning and operations.

India (Scott, G and Chopra, R, 2016)

GI provides spatial insights on basic infrastructure, other services and facilities, and the environmental condition of slums. This empowers local Government authorities in planning and executing slum improvement plans. Mapping and analysing changes in urban neighbourhoods to help planners and decision makers. Sustainable planning and management of population growth and urban expansion are achieved through continuous monitoring of an area.

Goal 5

It is often stated that countries with gender equality have better economies. Gender equality is derived from a range of measures, such as better health and education, but also land tenure, access to transport to employment, improved policing and fair taxing and benefits distribution (where these exist). The geospatial analysis of wider statistics data enables understanding and more focussed interventions.

Rwanda (DfID)

Esperance, 39, a mother of four used to be in constant dispute with her neighbours over ownership of the land she lived on. Through a DFID-funded land registration programme, the dispute is now settled and she is a proud landowner. Esperance says: “I will now work and invest confidently in my land to provide a better future to my four children as I now know that nobody can take my land from me.”

Goals 13, 14, 15

Natural resources and the environment. Sustainable management, particularly water sources and lakes, forestry, coastal zones, national parks and crop yield prediction. The planning and management of extractives industries is often aided by taking a geospatial approach. Sustainable management of the environment often also uses remote sensing data to give a current view on the state of natural environment, and climate change monitoring is enabled.

Zanzibar Sustainable Tourism

Balancing coastal development, growth through tourism, citizen and environmental demands is challenging. Land use, fisheries, property rights and the environment all need to be considered and decisions taken based on ‘where’ development best balances conflicting demands. Unregulated or illegal development can be identified and equally tourists, using innovative locally produced smartphone apps, can be encouraged to visit heritage sites. Geospatial data enables this.

Goals 8, 9

Internationally it has been demonstrated that the availability and use of maintained geospatial data can grow an economy by 0.25 to 0.6%, (Kedar J, 2017) in part due to better government and in part due to better businesses outcomes. Studies also demonstrate that benefits are evident across a wider-range of sectors, directly or indirectly. These studies are not directly transferable to developing nations. Examples include: marketing, telecoms, logistics, transport, extractives, financial services, tourism and utilities.

Most goals:

Disaster risk reduction and management. From famine to flood, disaster risk reduction and management demonstrates the importance not just of fundamental geospatial data, but of the need to integrate data from many sources rapidly to enable decision making. Weather forecasting to predict new rainfall, terrain data to model where and when flooding will occur, population data to estimate the impact, road data to understand how to conduct relief effort. Integrated location data such as this saves lives and reduces damage. Integrating government services saves money and improves lives. Online services rely on geospatial data such as national address and administrative boundary data. The ability to build services combining data from different government departments, or to update many different databases from a single entry, is increasingly commonplace.

Most sustainable development goals (SDGs), to which all UN member states have committed, aim to alleviate poverty and provide benefit to citizens. Geospatial data supports the achievement of many of the associated targets, through understanding, planning, decision-making, delivery, operations and measurement. Further examples are noted in the UN GGIM Paper “The Role of Geospatial Information in the Sustainable Development Goals”, which demonstrates the value of geospatial information to 5 particular SDG Goals.

Measuring the benefits of GI

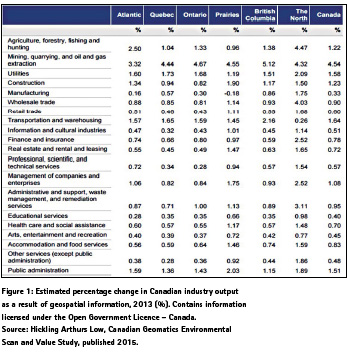

The benefits between nations, or even across a nation, vary considerably. Hickling Arthurs Low, Canadian Geomatics Environmental Scan and Value Study, published 2015, includes an examination of the estimated increase in industry output because of GI. The detailed figures themselves are not important in the context of this paper, but the table is extracted at Figure 1.

The first conclusion is that GI underpins across a wide range of sectors, a finding replicated in many studies of high income nations. The second conclusion is that, even in Canada, there are significant differences across provinces and territories due to differing needs and uptake. The use of GI, indeed different types of GI, therefore will vary across sectors and geographies.

This has worldwide applicability and the detailed benefits to every nation will differ. National economic benefit and Return on Investment Studies are justified and will also help determine GI priorities.

UN GGIM Europe’s Working Group on Data Integration is examining the integration of data, particularly INSPIRE data, to support SDG delivery and measurement. UN GGIM Europe has concluded that some INSPIRE data themes contribute to all Goals but is now looking more specifically at detail.

GI brings significant benefits to a nation across all sectors and to the economy. The level of economic benefit in low and middle-income nations is little understood and resource should be expended gaining this understanding in order to help investment decision makers consider whether and how to invest in national GI and associated institutional capacity and capability. The UNGGIM and World Bank MOU, ‘Roadmap for collaboration between World Bank’s Global Practice on Social, Urban and Rural Development, and Resilience and United Nations Statistics Division to assist countries to bridge geospatial digital divide’, signed at the 7th session of the UN Committee of Experts on Global Geospatial Information Management (UN-GGIM), provides a welcome step forward in trying to realise this gap in understanding.

Developing national geospatial agencies and capabilities

Traditional mapping agency role

NMGAs exist globally. Low-income nations may in part still use mapping from the last century, perhaps 1:50,000 scale, but neither maintained nor digital. Updates have been project-specific rather than through a maintenance regime, and many development projects do not consider the wider national benefits of data collected for a project. On the contrary, high-income nations maintain large scale, attributed and accurate data from addressing to topography, imagery to networks, and cadastre to geology.

In some cases, NMGAs have not recognised the changing world, and most have found it difficult to deploy the winning arguments for investment. These NMGAs are now left facing the stark reality that the World is moving on, that there are many geospatial players in government, it is no longer a simple customer/supplier relationship, and that they could become irrelevant.

For geo-political reasons, NMGAs are often ‘the authority’. This has benefits, for example in the philosophy ‘create once, use many’, but it also places a responsibility on them to lead the move into national spatial infrastructures and deliver the fundamental geospatial data that underpins the Nation’s data infrastructure.

Transforming NMGAs from surveying and mapping to delivering underpinning geospatial data to a nation is a challenge, a challenge that in UK took 30 years. The recent Ethiopian Government announcement that the Ethiopian Mapping Agency is being re-established as the Ethiopian Geospatial Information Agency shows that nations are rising to the challenge.

But nations need data now if SDG achievement is to benefit from this data, and so 30 year, or even 10 year, sustainable transformation programmes can only be part of the answer.

What is the future?

National mapping and geospatial agency director generals from across the Globe debated the future of their organisations at the 2017 Cambridge Conference. They concluded that NMGAs do have a future if they adapt.

▪ The increasing reliance on location, from delivery of SDGs to the internet of things, is an opportunity. Managing the fundamental geospatial data layer, fit for purpose, maintained and trusted, underpins the integration of all spatial data and allows better decisions and efficient delivery and operations.

▪ Future NMGAs may become data brokers as well as collectors/ managers, SDI authorities, service providers and service consumers. Whatever, NMGAs have to be the ‘go to’ authority for trusted fundamental geospatial data.

▪ NMGAs need to focus more on the user and their requirements over the next 10 years to deliver real value and their data must remain authoritative, trustworthy and accessible.

▪ In wider government, NMGAs can assist in integrating crossgovernment digital public services, helping realise their value in delivering SDGs. It is not enough to produce data; NMGAs need to be close to their customers and work to understand and solve their problems.

This is far more easily said than done. According to the UN Statistics Division, only 3% of Africa is covered at 1:25k scale, against 87% of Europe. For national coverage a number of nations use mapping from the last century, perhaps 1:50,000 scale at best, but neither maintained nor digital. Compare that with nations such as the United Kingdom and Singapore, maintaining large scale, attributed and accurate data from addressing to topography, imagery to networks. There is a widening geospatial divide, in itself contributing to the widening digital divide.

Nations are often investing heavily into land administration supported by the global community. A sustainable land administration system can bring economic and social benefits in line with SDG objectives. The need to collect and maintain geospatial data brings benefits more widely than SDGs though. It is part of a nation’s digital infrastructure. Improved availability of this geospatial foundation data leads to opportunities for better government, more transparency, effective urban planning, improved resilience, increased resource/asset and environmental management, and new business opportunities. But little investment is being made into national geospatial capabilities, the arguments still need to be won.

What are the challenges? (1) Cost, but innovative approached can reduce this, far more important in the first instance is demonstrating ‘value’. (2) People, who at all levels need to understand why geospatial makes a difference and how to use it. (3) Policy, primarily a willingness to share data in a manner that allows others to consume it. (4) A market ready and willing to use it and lastly, (5) winning the political and financial investment arguments. With these, investment can pay dividends.

Data as national infrastructure

The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) considered in 2015:

‘Data are an infrastructural resource – a form of capital that cannot be depleted and that can be used for a theoretically unlimited range of purposes.’

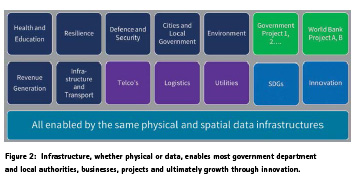

OECD likened it to roads and bridges that support a wide range of national and local uses from healthcare to profitable business, some unanticipated. The cost of such infrastructure is significant and the benefits are so widespread that no one use case can justify the investment on its own. Funding an underpinning, cross-cutting, data infrastructure therefore needs to be considered centrally. This is demonstrated for geospatial data in Figure 2.

The OECD continued:

‘Physical infrastructure such as roads and bridges enables benefits to ‘spill over’, for instance, by fostering trade and social exchanges. In the same way, greater access to data also has beneficial spill-overs, whereby data can be used and re-used to open up significant growth opportunities, or to generate benefits across society in ways that could not be foreseen when the data were created. But some of the spill-overs of data cannot be easily observed or quantified…. As a result, countries – and governments in particular – risk under-investing in data and data analytics and may end up giving access to data for a narrower range of uses than socially optimal. This risks undermining countries’ capacity to innovate…’

So, whilst the direct benefits of an infrastructure might be observable and measurable, and contribute to a business case, the spill-over benefits are not. The relative invisibility of these can lead Government to under-prioritise funding for the infrastructure. A paradigm shift is required: from governmentfunded data collection for its own purposes, to funding the facilitation of an ecosystem around an infrastructure.

The future NMGA will contribute to the step changes necessary and, as a key enabler, adapt or transform internally and externally. The remaining sections consider this change and how national mapping and geospatial agencies can remain core to the delivery of sustainable development going forward.

Leadership, policy and governance

It is a truism that, without the drive of leadership, achieving the benefits of geospatial information at national scale is not possible. Experience shows that identifying and incubating those political and business leaders is important. With leadership then governance can follow in a ‘coalition of the willing’. This then leads to policies that have ‘buy in’. Others will follow.

Nations do have geospatial information and many different government departments, agencies and businesses are collecting or procuring similar data for similar purposes. Bringing focus to ‘make once, use many’ as a policy driver is efficient and effective. It covers a sharing (including open data) but also clarity on who produces what data and services. Engendering the sharing of existing data is essential, not only will it improve efficiency but suppliers will seek to improve the data.

A singular NMGA collecting, managing and serving all fundamental geospatial data will be swamped in requirements. NMGAs have a developing role as a broker of trusted data for use by both government and the citizen. Policy should reflect this.

Policy needs to consider data priorities. Whilst the UN is developing the concept of ‘fundamental national geospatial data’, nations need to adapt this to their stakeholder needs – for example a nation may decide it’s data should support national priorities in sustainability of natural resources, green energy, health, agriculture, pollution abatement and resilience and prioritise creation and maintenance accordingly. Focusing on how geospatial solves problems, rather than the data itself, will serve NMGAs well. The paper demonstrates this need to focus more on the user and their requirements to deliver real value.

Volunteered Geographical Information and Citizen Science are creating ecosystems such as Open Street Map. Crowdsourcing requires different thinking about quality but has a valuable place in a nation. Likewise EO and other new collection techniques bring more data into the mix. Policy can address these; trust levels are dependent upon use; land tenure and GPS navigation require two different levels in data trust.

Cost

Communication is essential to winning funding. Ask a layman ‘should we invest in a ‘national spatial data infrastructure’ or three new hospitals and it is obvious what they will answer. We instil an element of separation through the term ‘Spatial’ where we should be shielding the complexity from the user.

To acknowledge the value geospatial data presents, it needs to be regarded as infrastructure; an infrastructure that is reliable, economic, accurate and trusted, which comes with an investment. Justifying that investment ultimately requires an understanding of the direct and indirect benefits, government revenue generation and economic value.

The UK Government’s Chief scientific advisor expressed the problem bluntly: Maps matter – It’s not enough to know they are important but WHY they are important. The local appropriation of simple, practical and tangible use cases is therefore essential – a universal approach is neither desired nor appropriate, with cultural and infrastructural variations as crucial considerations. Understanding the political drivers of a government offers the opportunity to approach geospatial matters in an accessible way, presenting the relevance of NMGAs in advancing towards sustainable development. In Jamaica, factors contributing to susceptibility to hazards include a lack of adherence to building codes and development in high risk areas. Reliable and timely geospatial information linked to data from other government agencies is helping reduce disaster risk and save lives.

But the other side of ‘cost’ is the need, on an international scale, to deliver Geospatial Information and Services quicker, cheaper and to a wider range of technological platforms and people. Solutions should be sustainable, and that requires partnership and collaboration over many years; we are developing a NMGA and national approach to geospatial. New solutions, such as cloud based managed services and greater use of cheap, accurate remote sensing coupled with automated feature extraction, will enable nations to remove risk and increase resilience whilst remaining in control and building internal capacity. And such solutions require a different financial model, perhaps more attractive to nations.

People

People drive change, and not just at the leadership level. The stairs of benefits realisation demand changes in culture, competence and attitudes, and they should be taken one step at a time. This particularly applies to NMGAs, where individuals that do change are often quick to depart, resulting a skills drain that governments find difficult to resolve.

A major challenge facing future governments is the lack of skilled manpower to develop and implement emerging technologies of all types. The involvement with capacitybuilding projects is crucial for a successful future, the long-term partnership approach. Partnering with academia is frequent, but how often do NMGAs have similar partnerships with business, the engine of growth?

Fundamental geospatial data

Spatial data infrastructure is a means to an end; many nations do not have formal spatial data infrastructures yet do have the components. The bedrock of a spatial data infrastructure is sharing data. A physical infrastructure on which to do this is a real advantage, but overcoming behavioural reluctance to share is often the real challenge, and any form of sharing can bring benefit. Geospatial data exists in all nations, NMGAs can help national agendas by leading the way on sharing existing data widely.

Development programmes funded by development banks and national aid can also set an example by insisting that all collected geospatial data, from imagery to cadastre, is shared. Provision of a small uplift in capability at a NMGA, as well as the data itself, can assist.

National institutions should manage fundamental geospatial data layers, many of which are the responsibility of NMGAs. Step changes are necessary.

▪ NMGAs should focus more on the user and their requirements over the next 10 years and develop priorities, data and services that meet customer needs. Data must be fit for purpose, and that purpose is evolving. The trend is towards increasing accuracy, frequent update, metadata and attribution, greater access and open standards.

▪ Stakeholder engagement is vital, and clear means of maximising benefits from limited resources, i.e. making choices, is required. In the 2017 Autumn Budget, the UK announced a Geospatial Commission that aims to derive greater benefit of geospatial data to the nation.

▪ To deliver real value data and services must remain trustworthy and in many use cases that data will have to be both trusted and authoritative data – cadastral or addressing data for example.

▪ At national level, and thus particularly in pursuit of SDGs, national coverage is important although data specifications might vary between urban and rural as do the use cases. SDGs also point to maintained data; not least because measurement of change is not possible if the very data has not changed.

The role of NMGAs can and will adapt.

▪ Nations will want to capitalise on all geospatial data and services, but which do they trust, which are fit for purpose? NMGAs may therefore become data brokers as well as collectors/managers. In so doing they can provide a level of assurance to users and add value through feature extraction, generalisation and integration services

▪ In becoming data brokers NMGAs will also become service consumers. Is it necessary to own assets to collect, manage and serve data? The answers may well be ‘yes’, but consuming a service for some components might be cost effective, meet capability gaps and reduce capital risk. The role of open data in a national infrastructure should also be considered.

▪ The NMGA may also become the spatial data infrastructure authority. There are strengths in this but also weaknesses. SDI is a pan- Government activity and a NMGA is really a data and service provider. If a NMGA has not been seen to share its data and services willingly, it may not have the credibility to lead SDI.

▪ Service provision is likely to feature increasingly, from smart phone apps to asset management.

Creating data is one side of a coin. The other side is use, often through integration to make effective decisions. This integration is the key to improved decisions and socio-economic benefits. In wider government, NMGAs can assist in integrating cross-government digital public services, helping realise their value in delivering SDGs. It is no longer enough to produce data and services; NMGAs need to be close to their customers and work to understand and solve their problems. There are several components to this:

▪ Education and Training.

▫ Educating decision makers, at all levels, in the benefits they can gain from geospatial capabilities, is a challenge. NMGAs need to be close to these stakeholders, seek to help solve their problems and then use these leaders as champions.

▫ Increasingly populations are using geospatial data without realising it – Uber and Google being obvious examples. Some education systems are recognising that there is an education component, using geospatial tools to help with school and University projects for example, and in some countries, national curricula mandate this.

▫ Training NMGA staff, data scientists, database managers, cyber security professionals, GIS operators etc. takes time and is expensive. Such individuals can be in short supply, and governments often lose such experienced professionals to the private sector. This is a real problem in low and middle income nations and can hold back NMGA development. It is another reason where alternatives, such as partnership with private sector for aspects of delivery may be beneficial. NMGAs can work with professional associations and Ministries of Education to promote the need for a suitable education pipeline.

▫ Integration through address, or place, is a key means of analysis and understanding – turning data into a picture. But a geospatial data is only one element of the data environment and geospatial representation is only one outcome – graphics, tables, answers to questions are equally relevant. Our education and training of geospatial ‘users’ must take this into account.

▫ NMGAs can help users gain more value through running cross-cutting workshops and masterclasses, both for government and business users, aimed at helping customers gain more value from geospatial data. Some of these could focus on particular SDGs and bring relevant ministries and businesses together.

▪ Organisation. NMGAs that stay close to their stakeholders are likely to best understand their needs. As ‘underpinning’ and ‘crosscutting’ data, stakeholder and customer groups provide the twoway communication that NMGAs need, and also the exchange of wider geospatial data between ministries. This is particularly relevant for ministries charged with delivering SDGs and statistics bureaus. NMGAs can help promote wider use of geospatial data in solving problems in this context, in turn increasing demand.

▪ Innovation. Businesses grow economies and create jobs. Helping grow new geospatial businesses is therefore in the interests of governments and their NMGAs. Two UK examples have wider relevance, ‘geovation challenges’ and a geospatial innovation incubator, the Geovation Hub. The latter is led by Ordnance Survey, supported by HM Land Registry and a number of other ‘big’ businesses and the Open Geospatial Consortium. It provides a real opportunity for entrepreneurs to develop ideas and then, if they have real value, and provides assistance in finding funding, including venture capital.

Winning the arguments

To be relevant, NMGAs and their partners have to be the ‘go to’ authorities for trusted fundamental geospatial data. But many NMGAs are significantly underinvested for today’s data challenge, and so arguments need to be built that open doors to investment, whether capital, operational or human.

There is, however, a shortfall in data available to convince decision makers. The benefits demonstrated in this paper, and many others, only serve to ‘whet the appetite’. Hard financial arguments are necessary, the ‘business case’ needs to include a ‘return on investment’ that shows demonstrable economic benefit, revenue benefit to government and the wider social benefits that are often difficult to place a dollar value upon.

Benefit studies of geospatial enablement are largely of high-income nations, and tend to indicate 0.2% to 0.6% GDP uplift. There are very few studies of low and middle income nations. One exception is Albania, where work to understand the financial benefits of an SDI was reported at the World Bank Conference on Land and Poverty in 2017 (Anand, A et al).

Recognising this, the UN and World Bank initiative to generate a global ‘best practice’ framework and a series of country ‘action plans’ is to be welcomed. These action plans set out the road map for change and seek to convince Finance Ministers that proposals are based on good practice and contain the necessary social and economic benefits necessary for decision making.

Transforming a mapping agency into an effective geospatial agency is a long-term programme, yet results will be expected immediately if SDG implementation is to be enabled by NMGAs. There are different approaches that can be combined in different forms to achieve this, different approaches that can strengthen or weaken a business case:

▪ a long-term ‘in-house’ capacity building approach, which may take a decade or longer to achieve, particularly developing the human capacity to meet technical capability.

▪ a technology solution through a project approach, with inherent project delivery and sustainability risks.

▪ a data collection and services project to provide useable data and services ‘once off’.

▪ A managed service that provides different components of capability, long term in partnership. This can bring ‘data today’, provide proven technology as a service and capacity building for tomorrow.

Transformation takes time and partnership with ‘transformed’ NMGAs can help with achieving sustainable solutions. The NMGAs may choose a managed services partner to help build initial GI data, so the nation benefits quickly whilst sustainable transformation is implemented.

Conclusion

The paper argues that NMGAs do have a future if they adapt. The increasing reliance on location, from delivery of SDGs to the internet of things, is an opportunity. Managing the fundamental geospatial data layer, fit for purpose, maintained and trusted, underpins the integration of all spatial data and allows better decisions and efficient delivery and operations. Future NMGAs may become data brokers as well as collectors/managers, SDI authorities, service providers and service consumers. Whatever, NMGAs have to be the ‘go to’ authority for trusted fundamental geospatial data.

NMGAs need to focus more on the user and their requirements over the next 10 years to deliver real value and their data must remain authoritative, trustworthy and accessible. In wider government, NMGAs can assist in integrating cross-government digital public services, helping realise their value in delivering SDGs. It is not enough to produce data; NMGAs need to be close to their customers and work to understand and solve their problems.

References

Anand, A, et al, (2017, March), Economic and Financial Analysis of National Spatial Data Infrastructure: An Albania Case Study, Annual World Bank Conference on Land and Poverty 2017 – Conference Paper

Chopra, R, (2016, June), ‘Urbanisation, Smart Cities, Slums and Geospatial Technology’, LinkedIn.

Department for International Development, (2013, September), Summary of DFID’s work in Rwanda 2011-2015.

Hickling Arthurs Low, (2015) Canadian Geomatics Environmental Scan and Value Study.

Kedar, J, (2017, March) ‘Geospatial Information drives benefits beyond land administration – why aren’t we taking them?’ at 2017 World Bank Conference On Land And Poverty

McCluskey, W et al, (2017, March) The role of ICT in delivering efficient revenue collection in developing countries: The Tanzanian experience, World Bank Land and Property Conference 2017.

OECD (2015), ‘Data-Driven Innovation for Growth and Well-Being. What Implications for Governments and Businesses?’, Directorate for Science, Technology and Innovation Policy Note, October 2015. http://www.oecd.org/sti/ ieconomy/PolicyNote-DDI.pdf

Ouiba, Y (2011) ‘Improvement of water supply through a GIS-based monitoring and control system for water loss reduction’, UNWater International Conference 2011 – Conference Paper.

Scott, G, (2016, March), ‘Positioning Geospatial Information to Address Global Challenges’, Annual World Bank Conference on Land and Poverty 2016 – Conference Paper UN GGIM, ‘The Role of Geospatial Information in the Sustainable Development Goals’ www.ggim.un.org

UNSD and World Bank, (2017, August), ‘Roadmap for collaboration between world bank’s global practice on social, urban and rural development, and resilience and united nations statistics division to assist countries to bridge geospatial digital divide’, http://ggim.un.org/meetings/GGIMcommittee/ 7th-Session/documents/ UNSD-GSURR%20Roadmap%20 for%20Collaboration-July17.pdf

The paper was presented at the “2018 World bank conference on land and poverty” The World Bank – Washington DC, March 19-23, 2018

(5 votes, average: 2.60 out of 5)

(5 votes, average: 2.60 out of 5)

Leave your response!