| Mapping | |

Drones in support of upgrading informal settlements: potential application in Namibia

We describe a rapid test of using an unmanned aerial system (UAS) to acquire geospatial data that can be used to facilitate planning, upgrading and to promote tenure security |

|

|

|

The number of people living in informal settlements around the world is difficult to measure precisely, but some estimates put it at close to one billion, or almost one quarter of the world’s urban population. Informality is a phenomenon that has become a common characteristic of large cities in developing countries. UNHabitat estimates that one third of all city inhabitants in the developing world live in an informal situation. People who live in ‘slums’, ‘favelas’, ‘pueblos jovenes’, ‘shanty towns’, and ‘squatter settlements’ all lack basic public infrastructure and services, live in inadequate housing and have no tenure security.

The UN Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) expressly addressed the problem of informality by setting one of the targets as “a significant improvement in the lives of at least 100 million slum dwellers” by 2020 (UN 2015). This goal has already been exceeded, but millions of people still live in slums. In the post-MDG era, the UN is promoting a “transformative approach” within the so-called sustainable development goals (SDGs) (UN 2014). Goal 11 of the SDGs is to “make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable.” (UN 2014, 14) It is clear from both the MDGs and SDGs that informal settlement upgrading is still high on the global policy agenda.

In many ways informal settlements are symptomatic of broader socioeconomic problems in society–poverty, inequality, and governance failures to name just three. The complexity of factors contributing to the rise and expansion of informality across the developing world means that good policies at the global or national level are just a start to successful upgrading and social upliftment of the informal residents.

Communities, local governments and NGOs, who play a linking role between these parties, are arguably the crucial players in upgrading. Ultimately, the goal of upgrading is to promote the safety, health and security of all of the residents living in the community. In the short term, the objective is to provide the means for the incremental upgrading of the community.

This paper describes the development and scope of informal settlements in Namibia and then proposes a novel approach to providing geospatial information to facilitate planning and upgrading of these settlements.

Upgrading of informal settlements

One of the fundamental principles behind incremental upgrading is to minimize the relocation of its residents and, if relocation is necessary, to relocate as close to the existing site as possible. However, relocation is typically required if the settlement is located in an environmentally sensitive area or in an area which is highly vulnerable to natural disasters like floods or hurricanes. The initial focus in upgrading should be on understanding how the settlement was formed, its relationship with the land owner and municipality, how it is organized and what services, if any, exist (NUSP 2015). Beyond that upgrading typically includes the following components:

• Planning and designing the upgrades

• Improving public infrastructure (roads, water, power)

• Land tenure regularization

• Upgrading of housing and shelter conditions

• Capacity development

Planning and designing upgrades involves designing streets and blocks in an area where settlement has occurred sporadically over time with little regard to vehicular access and in many cases no easy accessbyemergency vehicles. Planning, infrastructure design, tenure regularization, housing design andlocationand capacity development all require information and the participation of the inhabitants. UN-Habitat, through its Global Land Tool Network (GLTN), has developed a “participatory enumeration” toolthathelps compile basic information required for upgrading by involving the local inhabitants in the organization and collection of this information (UNHabitat/ GLTN 2010). This serves to build trust between external technical specialists and the inhabitants, but it also produces more reliable information and greater acceptance of the process and products. It is not only an information gathering activity but also a process for addressing conflicts and promoting consensus. One major challenge highlighted by GLTN is to ensure that the information collected in the participatory enumeration can be used to strengthen tenure security (GLTN 2014). This requires a flexible approach which recognizes a continuum of rights expanding the options for tenure security by offering alternatives to full private title, which can be expensive, time consuming and require standards that are not attainable in the short term in informal settlements. Instead, tenure security can be improved through recognizing some of the rights in the bundle of property rights, such as use and occupation, through a registerable certificate documenting these rights.

The participatory enumeration tool has been used effectively in several countries, including the Philippines, Thailand, and Brazil (UN Habitat/GLTN 2010). Lessons learned from this experience include:

• Strong partnerships with local authorities arecrucial

• The enumeration tool should be designed with the community so that it builds on local knowledge

• Training of enumerators is important and ultimately determines the quality of the data

• The data should be produced in a timely manner, which may require segmenting the work into smaller units

• Communities need to be trained to communicate effectively with other actors, such as local authorities

• The upgrading strategy may need to be promoted through advocacy (UN Habitat/GLTN2010)

Informality in Namibia

Namibia’s urban history is comparatively recent, but informal settlements have been a characteristic of settlement patterns since 1890 when the German occupation led to the development of colonial towns where the workforce for the white occupants was sheltered in informal settlements (Muller 1995).This pattern continued until the implementation of the South African apartheid policies in Namibia inthe1960s resulting in the replacement of informal settlements with racially divided townships. These townships were planned and surveyed and remained the property of the local authority who rented out the houses. Registration of properties in these townships only commenced only in the late 1970s.

Although apartheid rules began to be relaxed in the late 1970s, urban development was generally still strictly controlled and any informal structures were demolished. This led to overcrowding in cities like Windhoek where a 56 square meter house might be occupied by as many as 12 people (Simon1991). Informal settlements arose in traditional land areas which fell outside the formal planning and development controls that were applied to formal townships (Van Asperen 2014).

When Namibia gained independence in 1990, those in need of better income opportunities or shelter acted on their new freedom of movement and migration to urban areas increased. Local authorities, which previously demolished any unapproved structure, recognized that they could not meet the demand for shelter and so permitted the building of informal structures within formally planned areas. The first community initiative on land and housing, called Saamstaan (Standing Together), started in 1987. Their strategy was to acquire a communal plot which they could develop incrementally by themselves. Intheearly 1990s the newly formed Ministry of Regional, Local Government and Housing together with the para-statal National Housing Enterprise (NHE) and the City of Windhoek started a project to relocate in habitants from the overcrowded single quarters (hostels that accommodated male contract workers) tolots located on the western fringe of Windhoek. These households were permitted to construct temporary shelters while the National Housing Agency (NHE), a central government agency, would construct their houses as soon as they could afford these. When spontaneous settlements developed around these areas and another relocation project, the City of Windhoek responded by decriminalizing squatting and through their “Squatter Policy” implemented reception areas (Shipanga 2000). However, the households ontheseplots began to rent space to others thereby increasing the density of the settlement in the reception areas.

Upgrading initiatives and challenges in Namibia

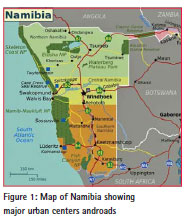

A ‘Development and Upgrading Strategy’ was implemented in various parts of the country with bilateral assistance from Denmark, France and Luxembourg. These projects focused on in-situ upgrading, although numerous households had to be relocated to meet the required standards for infrastructure.This experience showed that planning around existing structures was challenging and there was a shift toredesigning the area without considering the existing settlement patterns. However, upgrading in the northern towns (Oshakati, Rundu and Katima Mulilo) was mainly done in accordance with existing settlement patterns (see Figure 1). One important aspect throughout all of these projects was the key role of the community in the process. This role was mostly formalized by the local authorities working through existing or newly formed community structures.

Two NGO organizations, Shack Dwellers Federation of Namibia (SDFN) and Namibia Housing Action Group (NHAG), emerged out of the early initiatives of Saamstaan and developed strategies that promoted community involvement in the process. The Shack Dwellers Federation was created in 1998 as part of a poor peoples’ movement to promote the idea that decision-making and actions needed to be shared by the broader membership or community to make it more sustainable.

During the first phase (March 2007 to October 2008) of the Community Land Information Program CLIP) profiles of 235 informal settlements in 110 municipalities, towns, villages and settlement areas were compiled by the communities (Namibia Housing Action Group 2009). The second phase of CLIP includes structure numbering and mapping on aerial photographs (replacing the earlier practice of hand drawn maps) and door-to-door collection of socio-economic data and structure usage. Socio-economic surveys have been completed in 116 informal settlements in 64 urban areas. Once data is collected and verified by the community, that data is manually analyzed and the findings discussed with the community, local authorities and other stakeholders (e.g. regional councils). The focus of these discussions is mostly around the priority needs of the community.

Namibia’s general population is becoming more urbanized with 43% of the population living in urban areas in 2011 versus 27% in 1991. The data collected by CLIP revealed that the informal population in Namibia was around 500,000, equivalent to about 25% of the Namibian population. The upgrading process is currently still taking place within the formal land development process which means that eventually existing service tariffs will apply which communities cannot afford (Chitekwe-Biti 2013).

Another challenge is the lack of security of tenure experienced by households. The Ministry of Land and Resettlements started with a Flexible Land Tenure Program in the mid- 1990s to facilitate a simpler system to register tenure for households living in informal settlements. However, the Bill to enable the registration was only enacted in 2012 and the regulations guiding the implementation are expected to be proclaimed in 2015. Due to this delay, the City of Windhoek started focusing on planning for formal subdivision and individualization, therefore limiting the potential for applying appropriate standards and leaving thousands of households in a situation where two households live on 300 square meter plots.

Where upgrading is taking place the households sign lease agreements but do not have the right to upgrade and develop their property. They are therefore reluctant to invest in any upgrading of shelter improvements. Namibia lacks a common strategy for scaling up informal settlement upgrading in the country. The current slow pace of the formal land development process does not cater for scaling up upgrading and a dedicated longer term upgrading strategy is needed.

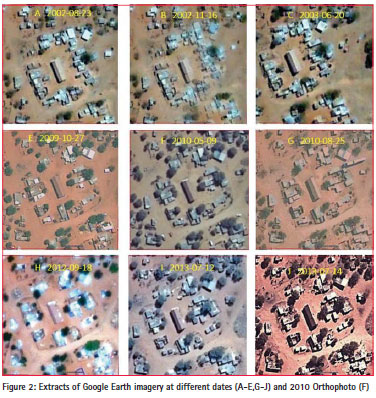

Mapping needs and availability

Map updating in a large and sparsely populated country like Namibia a costly per capita expenditure. Hence maps are only regularly updated in the major cities and towns of Namibia. In the 2010 enumeration of the Freedom Square upgrading project in Gobabis, the orthophoto maps used were produced from aerial photography dated May 2010 with a 0.5 m resolution (see Figure 2F). In addition to this orthophoto, satellite imagery such as that displayed on Google Earth could also have been used. Figure 2 shows extracts of a sequence of the available satellite imagery and orthophotos that are available for the Gobabis area. While the Google Earth satellite maps may be somewhat inferior in resolution and radiometric quality to the 0.5 m orthophoto (F in the figure 2), they are more frequently updated than the mapping that is typically done in Namibia. Comparing the quality of the Google Earth imagery dated 2009 (E in the figure 2) with that of the 0.5 m conventional orthophoto, one might argue that it was not necessary to incur the costs of producing the 0.5 m orthophoto. However, relying purely on Google Earth as the mapping source for settlement upgrading is not without problems. Firstly, the timing of updates cannot respond to the demands of small, under funded local project leaders. And since one cannot predict when Google Earth will render fresh maps one often has to either accept outdated or inadequate maps or provide for new mapping altogether. Secondly, the quality and spatial reference of the Google Earth satellite imagery is not constant. Hence the suitability of any given satellite map rendered by Google Earth has to be assessed specifically for each project, both in terms of resolution and currency.

Despite the above short comings, Google Earth is a valuable source of geospatial information often over looked in upgrading projects. Not only does Google Earth provide free access to an archive of satellite imagery taken over long periods of time, it also provides a very good viewer for visualization, basic drawing tools for the lay person as well as a widely used data standard (kml) for easy dissemination of geospatial information over the internet.

National mapping agencies typically try to update maps at regular intervals. To exploit savings through scales of economy, mapping contracts are typically issued to cover large tracts of land at uniform quality and resolution. More often than not mapping contracts of this kind are subject to complicated procurement procedures that often take more than a year to complete. Further more, many developing countries lack mapping capacities and hence have to rely on foreign companies, thus imposing even more bureaucratic complexity on the map acquisition process. The result of these impediments is that often projects are carried out with maps that are outdated or of inadequate resolution and accuracy or just not available due to delayed delivery. This is especially true for informal settlements which change very rapidly and require large scale mapping. Satellite imagery and aerial photography have been used in the past as the basis for mapping and planning informal settlements. However, the inappropriate scale and lack of currency make it challenging to work with this imagery. Google Earth, which is emerging as a very useful source of spatial data, often has the same shortcomings of currency and resolution. Fortunately, a new option has emerged which can provide current spatial information at an unprecedented resolution. The emergence of unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) and computer vision technologies has the capacity to overcome these impediments and provides the ability to augment satellite imagery for detailed urban design, rural planning and land administration tasks.

Rapid UAS test in Gobabis

Gobabis Town is situated in eastern Namibia approximately 200 km east of Windhoek (see Figure 1) and is the regional capital of the Omaheke Region and the core of Namibia’s “cattle country.” This municipality has four informal settlements incorporating approximately 9,000 people, including Freedom Square which is the oldest of the four settlements. CLIP covered all four informal settlements in Gobabis. Feedback meetings within the CLIP process provided a forum for the community to express its anger and frustration with the proposed relocations by the municipality. During an exchange visit in March 2013 to Cape Town and Stellenbosch, facilitated by SDI (Shack/Slum Dwellers International), participants were exposed to communities and local authorities using enumeration and mapping information collected by the community to upgrade and plan their settlement. As a result of this exchange, the Gobabis Municipality agreed to upgrade the informal settlement through re-blocking, and to sign a Memorandum of Understanding with NHAG/SDFN. This provided an opportunity to test a novel approach to mapping informal settlements and providing geospatial information for planning and upgrading.

Unmanned Aerial Systems (UAS) or drones are a convergence of navigational, positioning and model airplane technologies that provide a much more affordable and faster approach to mapping (Volkmannand Barnes 2014; Barnes, Volkmann and Barthel 2013). Most importantly, they offer a transparent methodology that can be quickly deployed. In dynamic situations like informal settlements a high resolution map can be obtained that is current to within less than a week of flying. The orthophoto map derived from the UAS aerial imagery is also much more understandable than mathematical coordinates or imaginary lines drawn between property corners. Additionally, it provides valuable information ontheroof type, house area, fences, paths and tracks, and other features that feed into the planning and adjudication processes. Namibia is fortunate to have a small group of model airplane enthusiasts (amongst them a land surveyor)who have exploited the large open spaces to pioneer the use of open source and do it yourself (DIY) UAV technology for aerial mapping and aerial surveillance for the protection of endangered wild life. The UAV community in Namibia has the capacity to design, configure and assemble multi-rotor as well as fixed wing platforms for Namibian applications.

We carried out a small pilot test in Freedom Square surrounding Gobabis to assess the potential for using small drones to facilitate incremental upgrading in informal settlements. It took the coauthor and some volunteers about a day to survey some 60 evenly distributed Ground Control Points (GCPs) across the Freedom Square area. Where possible, permanent and well defined features, such as manhole covers and disbanded tires (popularly used as flower beds), were used as targets. Most of the GCPs, however, consisted of white 20 cm paper plates secured to the ground with a 15 cm long nail. This survey was referenced to the local datum using post processed dual frequency GPS. During this survey the community was briefed on the UAV mapping process. Throughout the flying the weather was uncharacteristically windy and thus a considerable number of targets were disturbed either by children or by the wind before the image acquisition could be completed.

After on-site assembly of wings and fuselage the fixed wing UAV (known as Bateleur) was launched by catapult for a 20 minute flight at an altitude of 150 m covering approximately 100 hectares producing 4 cm GSD aerial imagery with 70% side- and 80% forward overlap. The flight ended with a perfect automatically executed landing which earned applause from the large number of community inhabitants who had gathered around the launch area. After downloading and inspecting the aerial imagery a second flight was performed to cover an additional 90 ha of land with aerial imagery of 4 cm GSD. Approximately 600 aerial images with 45 mm resolution (ground sampling distance or GSD) were acquired.

Figure 3 shows the logged flight path above Freedom Square as recorded by the flight controller on board the Bateleur. In its current configuration it has a takeoff weight of 2.5 kg, an endurance of over thirty minutes and flies safely at an airspeed of 14 m/s carrying a 20 MP camera as payload. It can thus cover a distance of over 25 km in one flight. It is made of material strong enough to endure full speed crashes and can be repaired in the field. The wing mountings are designed to disengage from the fuselage on impact, thus reducing the likelihood of damage andinjury.

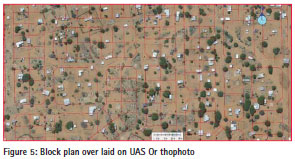

Using a ‘Structure from Motion’ (SfM) software suite (Agisoft’s Photoscan), these images were processed overnight to produce a high quality 4 cm orthophoto (see Figure 4) and digital surface model of the Freedom Square area. This orthophoto could have been delivered to planners, engineers, community members and administrators within less than 24 hours after the imagery was acquired. This UAS-based orthophoto is now being used by the Shack Dwellers Federation to finalize a formal block plan and to allocate formal parcels to the informal settler households. The proposed block plan is shown overlaid on the UASderived orthophoto in Figure 5.

Conclusions

Because this test occurred after the enumeration and lay-out planning phases of the Freedom Square project, we were unable to fully explore the potential value of the current, high resolution imagery and UAS products on the whole upgrading process. However, we are convinced that a UAS approach is superior to conventional approaches for the following reasons:

• It provides a resolution and currency unattainable by either aerial photography or satellite imagery

• It is cheaper than conventional approaches

• It provides a transparency and exposure to the community that is impossible with conventional approaches

• Capacity can be developed locally thereby avoiding long procurement processes and building on local knowledge

We are optimistic that over the next year we will be able to test this UAS approach further and demonstrate how it can provide quality geospatial data for tools such as the social tenure domain model (STDM).

References

Barnes, G., W. Volkmann and K. Barthel (2013). Using Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) to Democratize Spatial Data Production: Towards Spatially Enabling Land Administration. Proceedings of Annual World Bank Conference on Land and Poverty, Washington, DC

Chauke, P., M. Muthige and A. Coville (2011). Measuring Success in Human Settlements Development. Presented at DIME Seminar, July 2011, Washington, D.C. http://microdata. worldbank.org/index.php/catalog/1041

Chitekwe-Biti B. T. (2013). Impacting the City: The Role of Social Movements in Changing the City’s Spatial Form in Windhoek, Namibia. A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities.

GLTN (2014). Access to land and tenure security. UN-Habitat, GLTN, Nairobi, Kenya. http://www.gltn. net/index.php/land-tools/themes/ access-to-land-and-tenure-security

Namibia Housing Action Group (2009). Community Land Information Programme (CLIP). Profile Of Informal Settlements In Namibia. Report, Namibia Housing Action Group,Windhoek.

Namibia Housing Action Group. (April 2014). Kanaan Report: Community Land Information Programme (CLIP). Report, Namibia Housing Action Group,Windhoek. Namibia Housing Action Group. (June 2014). Participatory Planning for Informal Settlement Upgrading in Freedom Square. Gobabis: SDI-AAPS Planning Studios. Report, Namibia Housing Action Group, Windhoek.

NUSP (2015). NUSP Resource Kit, National Upgrading Support Programme. South Africa. http://upgradingsupport.org/ content/page/part-1-understandingyour- informal-settlements http://mirror.unhabitat.org/pmss/ listItemDetails.aspx?publicationID=2975

Shipanga, M. K. (2000). Squatter Settlements in Windhoek: Analyzing the Challenge and Policy Response of the city Council. A thesis submitted to the University of Namibia for the degree of Masters of Arts in Public Policy and Administration.

Simon, D. (1992). Windhoek: desegregation and change in the capital of South Africa’s erstwhile white colony. In Lemon. A.(Ed.). South Africa’s Segregated Cities. Bloomington Indianapolis and Cape Town, Paul Chapman and David Philip

UN (2014). The road to dignity by 2030: ending poverty, transforming all lives and protecting the planet. Synthesis report of the Secretary- General on the post-2015 sustainable development agenda. http://www. un.org/en/ga/search/view_doc.asp?sy mbol=A/69/700&referer=http://www. un.org/en/documents/&Lang=E

UN (2015). Millennium Development Goals and Beyond 2015. http://www. un.org/millenniumgoals/environ.shtml

UN-Habitat/GLTN (2010). Count me in – Surveying for tenure security. United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-HABITAT), Nairobi, Kenya.

Van Asperen, P. (2014). Evaluation of innovative land tools in sub- Saharan Africa. Three case from a peri-urban context. Sustainable Urban Areas 49. Amsterdam, IOS, Delft University Press.

Volkmann, W. and G. Barnes (2014). Virtual Surveying: Mapping and Modeling CadastralBoundariesUsing Unmanned Aerial Systems (UAS). Proceedings of XXV International Federation of Geomatics (FIG) Congress, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

World Bank (2013). Is Upgrading Informal Housing a Step in the Right Direction? Webinar organized by the South Asia urban team at the World Bank. The paper was presented at the “2015

World Bank Conference on Land Andpoverty” The World Bank – Washington DC, March 23-27, 2015

(30 votes, average: 1.03 out of 5)

(30 votes, average: 1.03 out of 5)

Using remote control planes (I guess you can also call them drones) has been used for quite some time to do aerial photography. Also to take Google Earth as a standard on satellite imagery for detail survey work is concerning. GE is a useful tool for initial overview assessment but definitely not adequate for detail surveying, especially in Africa where Google cut and paste to create a nice seamless (often not even that seamless) pretty picture There are a number of other satellite imagery products available on a resolution suitable for detail planning. so yes, using drones is one method, but definitely not that new and it may be a lot easier to use existing sat imagery which will spare you a lot of post processing of the aerial images collected with the drone.

Leave your response!