| Mapping | |

Systematic cadastral registration using UAV technology

The paper presents the results of scaling up the use of UAV technology for registration of property rights in the Republic of Kosovo, while showing practical challenges faced and lessons learned |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Activities for land administration, cadastral mapping and registration of real property rights in the Republic of Kosovo are priority components for the country’s economic development strategy. In this context, the development of the national spatial data infrastructure (NSDI) is also an integral approach because cadastral data are a core spatial data set. The purpose is to update cadastral data, using new technology and highlight transparency.

With the support of the World Bank-financed Real Estate Cadastre and Registration Project (RECAP) progress on systematic updating of cadastral data is underway through cadastre reconstruction which has updated thousands of properties in more than 100 cadastral zones of 16 municipalities. Even though much progress has been made, many properties remain at a legal standstill due to issues such as inheritance. The legal and technical issues have been analysed and lessons learned discussed, with the conclusion that it is appropriate to test a new mapping and property rights registration toolkit for faster, cheaper, citizen-centric cadastral mapping and recording of land rights.

In 2013 and 2014 the World Bank team successfully piloted the use of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs or “drones”) as a way to produce faster, fit-for-purpose spatial data (aerial photographs, orthophoto maps, and 3-D models). Typically, project costs for aerial surveys are hundreds of thousands or millions of dollars and can use up to 25% of the project budget. The maps using the conventional method take months to be produced, by which time the situation has already changed. The team’s tests in 2014 demonstrated how UAVs allow local map production with very high accuracy (4-8 cm) in a matter of days. In addition to maps, the technology can produce 3-D models that can be used for multiple purposes.

In 2015 the World Bank’s Innovation Labs purchased a fixed-wing UAV to support operations and in December the team, together with the Kosovo Cadastral Agency (KCA), mobilized the UAV to support the national cadastral reconstruction program. This work is the first phase of a broader task to combine UAV technology with the use of free, customizable open source registration software (OSS) that is easily deployable in the field on tablets for data collection. Combining the UAV and OSS will put the Kosovo Cadastre Agency at the forefront of developing and testing an innovative mapping/registration tool kit and methodology in a national-level government project. It is believed that the combination of new technology can revolutionize the way the Bank and its clients design, implement, and monitor projects by making these processes more accurate and more cost effective. It also allows improvements to the way governments and/or local communities map and record property rights. Ultimately the combination will be assessed for suitability in diverse scenarios: Post-conflict/Post-Disaster response (quickly mobilizing fast and cheap technology to record the facts on the ground and collect information from survivors), community based mapping and recording rights (indigenous and vulnerable communities), and mainstream registration.

This paper will present the results of scaling up the use of UAV technology to the production level as well as some of the practical challenges faced and lessons learned.

Using UAV technology for cadastre reconstruction

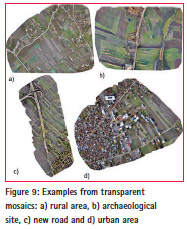

The UAV was used in three diverse settings:

• Rural Setting: In 1999, a lot of men and boys of the Krusha e Madhe village in southern Kosovo were massacred in the Balkan conflicts. The women of Krusha have been slowly rebuilding their community and have organized several agricultural cooperatives. However, the ownership of their land/houses remains unregistered or registered in the names of the deceased men thereby increasing tenure insecurity and preventing the land from being used as an effective economic asset. The time, cost and complexity of conventional cadastral surveying and registration is one of the key constraints for the women. Thus, about 1200 hectare (ha.) village was selected for the UAV work. The work is ongoing to update the cadastral information and this zone will be the first area where the new OSS will be used for field data collection of ownership information as part of the Phase II activity, which started in April 2016.

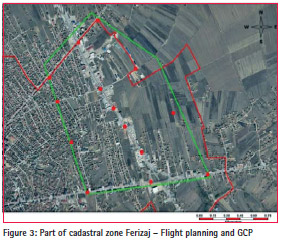

• Urban Setting: Over the past two decades many cities in Kosovo have experienced rapid, unplanned urban expansion resulting in informal settlements, illegal constructions and chaotic development. The Government of Kosovo has introduced a program for land owners to legalize their property rights and municipalities are working to integrate the new developments and provide services to citizens. In order to facilitate decision making, improve planning and prioritize investments, the team chose part of the city of Ferizaj for the UAV work. Work is ongoing to update and complete the cadastral and ownership data according to the actual situation on the ground. The information will also be used to assess its relevance and suitability for the legalization program, and the 3D models will be assessed for suitability for urban planning, infrastructure development, taxation etc. as part of the Kosovo Cadastral Agency’s role in developing and promoting the NSDI.

• Road Corridor: Although the initial focus of the work was to integrate UAVs into the cadastral mapping process, the team responded to a spontaneous request for assistance on construction of the R6 national highway. While flying in the urban zone near the new highway, a municipal representative noted that the road crew had recently found an archaeological site. The available aerial imagery and maps provided no evidence of the site. With the UAV the team was able to plan, fly and process a very high resolution 3D map at and around the area in less than 24 hours. This provides fresh and accurate information for rerouting the road, cultural heritage preservation and other important decision making.

Process of implementation and processing of the data

The objective of the pilot project in the selected areas, Krusha e Madhe, Ferizaj and highway Prishtina- Skopje, which is under construction, is to test whether we can use the UAVs (Unmanned Aerial Vehicles) in future cadastre reconstruction projects to be implemented by the Kosovo Cadastral Agency. Therefore the project’s aim is to test the required level of accuracy for cadastral surveying according to the standards in Kosovo. Overall the advantage of UAV systems lies in their high flexibility and efficiency in capturing the surface of an area from a low flight altitude. In addition, further information such as ortho images, elevation models and 3D objects can easily be gained from UAV images. Altogether, this project endorses the benefit of using UAVs in cadastral applications as well as new opportunities they provide for future cadastre reconstruction projects in Kosovo.

Preparation phase

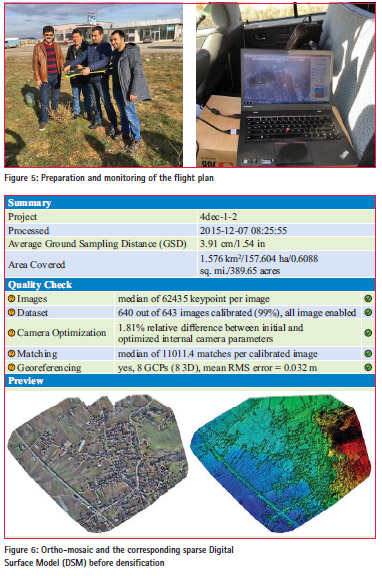

The preparation phase started in November 2015, when the flight approvals were obtained from the Civil Aviation Authority of Kosovo and KFOR/NATO. Additionally, the officials of Municipal Cadastral Offices in Rahovec (for cadastral zone Krusha e Madhe) and Ferizaj were informed with the details of the pilot project. In the beginning of December 2015 the World Bank team together with the Kosovo Cadastral Agency (KCA) (The World Bank team includes Kathrine Kelm, Dr. Bruno Sanchez-Andrade Nuno, Eric Sundheim, geodetic surveyor from Geomatikk Norway; Ana Jesenicnik cadastral engineer from Sensefly Switzerland; and Qazim Sinani and Korab Ahmetaj, cadastral surveyors from the Kosovo Cadastral Agency), mobilized the UAV to test the use of this technology for cadastre reconstruction projects in the abovementioned locations.

Krusha e Madhe was selected among the rural zones, whereas a part of the cadastral zone of the municipality of Ferizaj was selected among the urban zones. Part of the new highway Prishtina-Skopje that is under construction was also selected, along with archaeological sites which were discovered during the excavation of the new highway.

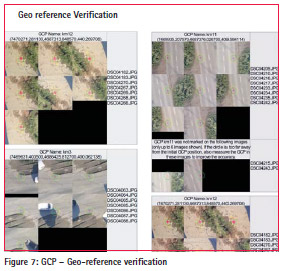

Before being able to fully employ the UAV technology, the team was initially required to mark in the field Ground Control Points (GCP). The importance of these points is for the post processing phase of the images in order to geo reference the blocks. For good coverage, of one block of size 0.5 km by 0.5 km at least 5 GCP were planned.

The blocks of flight were planned to last approximately 30 minutes per flight. Flight planning is made according to the division of the zone: the urban constructed part, the rural zone with agricultural parcels, and the zones with height differences for the photographing effects with various resolutions depending on the flight altitude.

The cadastral zone Krusha e Madhe was divided into 14 flight blocks with 41 GCPs marked in the field. In this case the border points between blocks were also used for the neighbouring block. The urban part of cadastral zone Ferizaj, was divided only in one block, with 16 GCPs marked in the field.

Field work activities

The field work started after the preparatory phase, which included planning of the blocks of flight as well as the planning of the marking the of GCP in the selected zones for this project. The selection criteria for finding a suitable location for marking the GCP in the planned zones were: having an accessible point, no obstacles in front, proper visibility, and a sustainable ground. The cemented parts, such as sidewalks, the edge of roads in the asphalt, were preferred, provided that they were not located in the space where the traffic transited, because the color could be damaged due to the circulation of the vehicles, as well as due to the risk that the marking could be covered at the time of flight. In order to mark the GCP with color, a template in the form of a cross, with wing dimensions of 25 cm by 10 cm was designed.

The points in the field were numbered with ordinal number for easier identification in the picture. Hereafter, these points were measured with GNSS rover by using KOPOS-Kosovo Positioning System. Each point was measured three times aiming to calculate the average for the accuracy of measurements such as standard deviation.

After marking the GCP for a block, preparations were made to survey the block with the eBee drone. This is done through the software eMotion2, where initially the planned block was inserted, and then the space was defined through eMotion2 software. Beside this, other parameters were set as well, such as: altitude, resolution, coverage between the images, wind speed, the launching point of the drone, and the landing point, at which point this plan was stored with a new name.

After making all the preparations, the drone was prepared for the flight with the camera in place. The Cannon 4.2 and Sony 3.2 cameras were used. Before launching the drone for the flight, the flight plan that was created earlier was inserted and the list of all parameters about the state of the drone, state of camera, the battery as well as the wing direction were checked.

When all conditions were fulfilled according to the control check list, the drone was ready for flight.

After successful launching, the drone flew in a spiral form until it reached the altitude that was previously determined. Once it reached the certain height the photographing started in accordance with the flight plan. Upon completion of the block the drone returned and landed to the previously determined point.

Image processing

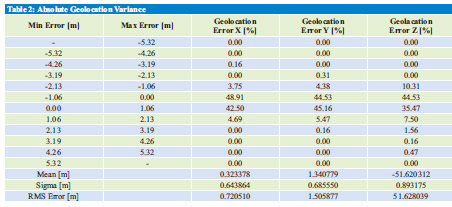

Image processing was done automatically through the Post flight Terra 3D version 4.0.89 software. After the processing, along with the products, the software generated a quality report with some examples as explained in figure 6.

Ground Control Points

Localisation accuracy per GCP and mean errors in the three coordinates directions. The last column in Table 1 counts the number of calibrated images where the GCP has been automatically verified vs. manually marked.

Absolute Geo location Variance

Min Error and Max Error represent geolocation error intervals between -1.5 and 1.5 times, the maximum accuracy of all the images. Columns X, Y, Z in table 2 show the percentage of images with geolocation errors within the predefined error intervals. The geolocation error is the difference between the initial and computed image positions. Note that the image geolocation errors do not correspond to the accuracy of the observed 3D points.

Results of the project

The field recording with UAV technology was a new and special experience for experts and management of the Kosovo Cadastral Agency. This was done with concrete support from the World Bank to the Kosovo Cadastral Agency in order to test the innovative approaches for the cadastre development in the Republic of Kosovo and beyond.

During the first phase in December 2015, after finalizing the processing of data, orthophotos were created with a resolution of 3 to 6 cm and with an accuracy of up to 1 cm. Whereas during the second phase, in April 2016 in Cadastral Zone of Krusha e Madhe where created new orthophoto by using the Drone without GPS/RTK and for same area was used Drone with GPS/RTK. Also it was used the thermal camera to create orthophotos for agricultural needs. The produced orthophotos from 2016 will be used in the second phase of the pilot project which consists in the reconstruction of the cadastral information on the part of cadastral zone Krusha e Madhe and Ferizaj. This process will continue with the digitization of cadastral units based on these orthophotos as well as their decoding, door to door along with the owners and members’ of the community input. A pilot for a block of parcels using both decoding and OSS-an application produced by Cadasta (Cadasta Foundation is dedicated to the support, continued development and growth of the Cadasta Platform – an innovative, open source suite of tools for the collection and management of ownership, occupancy, and spatial data that meets the unique challenges of this process in much of the world.) which is for data collection based on the filed form that is being used during Cadastre reconstruction, shall be implemented.

Another result is the DSM (Digital Surface Model). This product enables the creation of the 3D orthophotos. The UAV method allows for the derivation of much more information. Based on the image orientation, a digital elevation model of different grid and area sizes can be calculated. In addition, 3D models of objects such as buildings can be generated based on the captured UAV data.

The final textured model can be exported as VRML (Virtual Reality Modelling Language) for general 3D viewers or as a KMZ file for display in Google Earth.

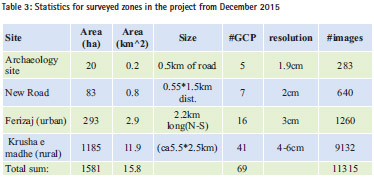

As part of this pilot project 1,581 ha were recorded in four different zones including: urban, rural and archaeological zone as well as in a part of a highway that is under construction.

Sixty-nine GCPs were previously marked in all these zones, whereby the largest part is in Krusha e Madhe, which also includes the largest surface for which surface images were taken.

The resolution of the images was determined depending on the part where the drone flight took place, starting from 1.9 cm for the archaeological part and up to 4 to 6 cm for the rural part in the cadastral zone Krusha e Madhe. The total number of images taken after completion of all flights of all planned zones is 11,315 images.

The analysis of the produced data to be used for the cadaster purposes

The use of the UAV technology and Open Source Software in this pilot project was initiated in order to analyse whether these products (orthophotos) offer accuracy according to the tolerances determined by the Law and Administrative Instruction for use in the cadastre in Kosovo.

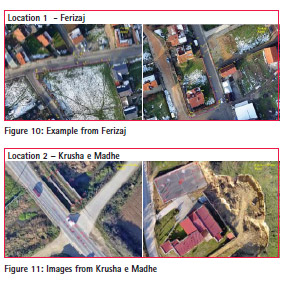

The selection of the cases was conducted for analyses from orthophotos from two locations: Ferizaj and Krusha e Madhe. In these cases the elements such as: the boundaries of the parcels, fences, walls, pavements, white lines on the road, houses etc., were manually digitized in orthophotos. Furthermore the selected cases and the digitized ones were measured in the field with GPS/GNNS, whereas the houses were measured with Total Station.

On location 1 (Ferizaj) are measured 176 points as shown above. As can be seen from the sketches there are measured houses, walls, fences, sidewalks, electrical poles, pits.

The measurements in the field are compared to the similar points digitized in orthophotos.

On the walls, fences, sidewalks, poles the difference is between 1cm and 5cm, on the buildings the difference is 7cm.

On location 2 (Krusha e Madhe) there are measured 181 points. As seen in the sketches above there are houses, walls, train rails, white lines on the road and stadiums. The measurements in the field are compared to the similar points digitized in orthophotos.

On the walls, fences, white lines the difference is between 2cm and 10cm. On the buildings the minimum difference is 20cm.

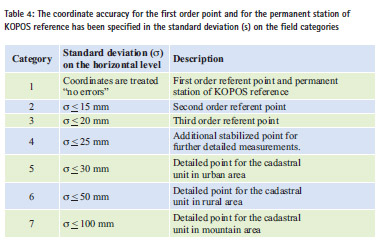

Based on the “Framework No. KCA 2013/02 on the Standardisation of Measurements and Cadastral Surveys “article 6, “Standard deviation of measurements and cadastral surveys”

Standard deviation (s) is the unit for assigning the accuracy of the geodetic measurements which is also applied in the measurements as well as in the cadastral surveys. The coordinate accuracy for the first order point and for the permanent station of KOPOS reference has been specified in the standard deviation (s) on the field categories as mentioned in table 4.

The preliminary results do not fully comply with the Framework No. KCA 2013/02, therefore, at the beginning of April, a new flight took place with another model of drone equipped with GPS/RTK. The products/orthophotos gained with this new methodology, are used for the second phase of the project which is: Reconstruction of Cadastral Information with UAV and Open Source Software technology that is aiming to identify properties based on the orthophoto-products gained through this technology.

Lessons learned

There were several lessons learned at various stages of the implementation of this project:

Preparation stages:

a. Acquiring permission for flights: it was important to determine the authorities from whom the team needed permission for the flights to take place. Additionally, it was helpful to know the timelines by which such permissions were given in order to begin communication with the local population as well as necessary officials in the zones before and during flying for permission to use land such as airports, etc.

b. Work Flow: it is necessary to set up Ground Control Points (GCPs) 1 to 2 days before flying. It is also important to have flight planning considerations (such as climate, etc.) as well as the ideal team members participating.

c. Data Processing: there must minimum “Big Data” processing and storage requirements that need to be planned for and met. For example, in the team’s case the initial KCA computer that was set up was too small and slow. There need to be considerations for processing times as well as setting up the workflow by thinking about what is done automatically by the program and what needs manual input.

External factors

In order to use an UAV in the Cadastre, it is important to select the period of the year when the vegetation is at a minimum. The most suitable time is in the early spring or autumn. On the other hand, in these periods of time the atmospheric conditions may not be stable, as was the case with the pilot Project in Krushe e Madhe. In that case due to the fog, the team had some daily delays and was not able to perform the flight on the given days.

“Marking the boundary of parcels”

To have the best benefits from UAV for Cadastre it is better to have an Awareness Campaign for several weeks, with owners/users of parcels. The Awareness Campaign would be used as a tool to inform and request from owners/users to mark and color the boundary points of parcels. After marking the boundaries, the flight could take place and from the orthophoto gained the boundaries will be easily identify by the owners/users.

Findings and conclusions

Time and cost savings – The advantage of UAV systems is the ability to quickly observe the surface of areas at low flying altitude while still meeting the accuracy requirements and standards of the Cadastre in Kosovo. For example the ortho image with high accuracy was produced for a part of the cadastral zone of Ferizaj within 24 hours. About 293 hectare are surveyed and processed up to the final product. Usually when surveying with the conventional methods using GNSS technology for the same size area, would have taken up to 10 working days, assuming the atmospheric conditions permitted.

Additionally even though the team’s initial work was focused on integrating UAVs into the cadastral mapping process, they received a spontaneous request for assistance by the highway authorities. A municipal representative informed them that a road crew had recently found an archaeological site near a highway under construction. The available aerial imagery at the time provided no evidence of the site. The team quickly mobilized the drone to produce a high resolution 3D map of the area in less than 24 hours. This provided fresh and accurate information for rerouting the road, additional land acquisition needs, cultural heritage preservation and other important decision making issues.

UAVs are rapidly becoming an effective tool for mapping in many diverse scenarios and the work in Kosovo demonstrates only a few examples of their potential. Therefore, by using the UAV technology these projects will be accomplished by spending less time and with more quality within the tolerances set by the law on cadaster and administrative instructions for the Reconstruction of the Cadastral Information.

Local Capacity and Production: Moreover, the Kosovo Cadastral experts have been introduced for the first time to a new technology for the needs of cadaster. They are also trained to use this new technology starting from planning, surveying and processing of data offered by this technology.

“Fit for Purpose mapping”- A new way to envision national mapping and systematic registration programs: The UAV technology is an easy procedure which is easily transferable to local experts and the processing and production of final orthophotos can be handled locally as well. The beneficiary organizations can, in a straightforward manner, update the information for smaller areas with local capacities, instead of using big international contracts, which are used mainly for national level aerial photography.

“On demand” services for multiple sectors: UAV technology is flexible and has the potential for multiple uses across diverse sectors. This can be seen in an example in this very project where the team was able to mobilize quickly to account for the archeological site discovered during the high infrastructure project. Additionally, UAVs produce richer data: DEM and 3D models, which will help build up KCA’s NSDI for both public and private sector benefit.

Beyond the Kosovo Cadastral Agency’s use of this technology, the UAV measurements can present a great benefit to other users of cadastral data, such as private licensed surveyors, real estate agencies, insurance companies etc. In areas where access can be difficult, UAVs can offer a valuable alternative to conventional measurement equipment such as the total stations and Kosovo Positioning System (KOPOS). In the future, UAVs will be used where a need for high accuracy is required and fast data capturing is needed. Therefore, the use of UAVs is an opportunity for cadastral surveying in the future.

References

1. Aide Memoire. Real estate cadastre and registration project (RECAP) implementation support mission November 30 to December 11, 2015;

2. Barnes, G. Volkmann, W. Sherko, R. Kelm K. 2014. Drones for Peace: Part 1 of 2 Design and Testing of a UAV-based Cadastral Surveying and Mapping Methodology in Albania. Annual World Bank Conference on Land and Poverty. The World Bank – Washington DC, March 24-27, 2014;

3. Kelm, K. Tonchovska, R. Volkmann, W. 2014. Drones for Peace: Part II Fast and Inexpensive Spatial Data Capture for Multi-Purpose Use. Annual World Bank Conference on Land and Poverty. The World Bank – Washington DC, March 24-27, 2014;

4. Manyoky, M. Theiler, P. Steudler, D. Eisenbeiss H. 2011. Unmanned Aerial Vehicle in Cadastral Applications. International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Vol. XXXVIII-1/C22 UAV-g 2011, Conference on Unmanned Aerial Vehicle in Geomatics, Zurich, Switzerland;

5. Meha, M. Çaka, M. 2013. The effect of law on cadastre and address system for sustainable land governance in Kosovo. Annual World Bank Conference on Land and Poverty. The World Bank – Washington DC, April 8-11, 2013;

6. Meha, M. Steiwer, F. Bublaku, H. 2011. Procedures for registration of property and services on Cadastre. Publisher Kosovo Cadastral Agency. 2011. Rome, Italy;

7. Law on Cadastre No. 04/-L-013. Official Gazette of Republic of Kosovo / no. 13 / 1 September 2011, Prishtina;

8. World Bank website news (January 07, 2016). Drones Offer Innovative Solution for Local Mapping. http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2016/01/07/drones-offer-innovative-solution-for-local-mapping

Paper prepared for presentation at the “2016 World Bank Conference on Land And Poverty” The World Bank – Washington DC, March 14-18, 2016

Copyright 2016, by Murat Meha, Kathrine Kelm, Muzafer Çaka, Qazim Sinani and Korab Ahmetaj. All rights reserved.

(518 votes, average: 1.05 out of 5)

(518 votes, average: 1.05 out of 5)

An interesting article that takes the glass being half-full approach.

It is perhaps more sobering to reflect on a recent article by Anthony Wallace on the pitfalls of UAV imagery acquisition and application – the glass being half-empty!

http://www.spatialsource.com.au/20-things-they-dont-tell-you-about-uavs/

In this link, Wallace sets out 20 things they don’t tell you about UAVs. In brief:

#1. A UAV is just a platform for a sensor

#2. A small UAV carries a small payload which means small format sensors

#3. A $1,000 sensor is not as good as a $1.5m sensor

#4. A UAV is not unmanned

#5. Labor costs make small UAVs uncompetitive

#6. UAVs are justifiably limited by airspace regulations

#7. Line of sight is no more than 500m

#8. You will need formal training to operate a UAV legally

#9. A UAV is capable of killing you.

#10. UAVs suffer from local environment effects (especially wind)

#11. The logistics of UAV operation are problematic

#12. Blurry images cannot be used to generate accurate results

#13. Eagles hate UAVs

#14. The capital cost of a UAV is significant

#15. UAV crashes are common

#16. UAV insurance is hard to get

#17. You will need Professional Indemnity Insurance if you offer an aerial surveying service

#18. If you’re not skilled in photogrammetry, you’re not an aerial surveyor

#19. Airborne GPS and IMU for UAV are not accurate enough for direct geo-referencing

#20. While we’ve all been watching UAV developments, other things are happening.

The details under each point are very profound. Please visit the link. All very sobering!

Now the current article by Meha, et al, reports that work over a project area of 293 ha could be completed in 24 hours opposed to 10 days with conventional technology. But this doesn’t allow for the very large number of GCPs – that don’t get created instantly! So that is just one of the issues that is ignored in Meha’s article.

Overall Meha’s article is really reporting on an ideal scenario, intended to bolster an emerging work program.

Also it seems that there are many laws surrounding the use of drones in Kosovo. Meha’s article provides almost no attention to these, other than approvals were sought.

In many countries, with systematic registration significant work must be done to understand the complex legal, social and historic issues. That can only be done by boots on the ground and it takes time to resolve conflicts and other land disputes. With such histories land occupants want to see monumentation on the ground as proof positive of boundary determination and not just digits created by imagery. This article gives insufficient attention to these issues.

Drawing on Wallace’s pragmatic observations, he sagely concludes:

“The UAV industry is what it is – there is no doubt that UAVs have many intriguing applications in many fields, although we have seen the existing service providers back-pedalling from things like pizza delivery or parcel delivery. At the current rate of development and with the concentration of resources being applied to the industry there is no doubt that further advances will be rapidly made.

But beware of the hype, and remember, in our industry it’s not about the platform, it’s about the sensor.”

Nonetheless let me congratulate Meha, et al, for this thought provoking article in Coordinates. Be wary of spin!

An interesting article that takes the glass being half-full approach.

It is perhaps more sobering to reflect on a recent article by Anthony Wallace on the pitfalls of UAV imagery acquisition and application – the glass being half-empty!

http://www.spatialsource.com.au/20-things-they-dont-tell-you-about-uavs/

In this link, Wallace sets out 20 things they don’t tell you about UAVs. In brief:

#1. A UAV is just a platform for a sensor

#2. A small UAV carries a small payload which means small format sensors

#3. A $1,000 sensor is not as good as a $1.5m sensor

#4. A UAV is not unmanned

#5. Labor costs make small UAVs uncompetitive

#6. UAVs are justifiably limited by airspace regulations

#7. Line of sight is no more than 500m

#8. You will need formal training to operate a UAV legally

#9. A UAV is capable of killing you.

#10. UAVs suffer from local environment effects (especially wind)

#11. The logistics of UAV operation are problematic

#12. Blurry images cannot be used to generate accurate results

#13. Eagles hate UAVs

#14. The capital cost of a UAV is significant #15. UAV crashes are common

#16. UAV insurance is hard to get

#17. You will need Professional Indemnity Insurance if you offer an aerial surveying service

#18. If you’re not skilled in photogrammetry, you’re not an aerial surveyor

#19. Airborne GPS and IMU for UAV are not accurate enough for direct geo-referencing

#20. While we’ve all been watching UAV developments, other things are happening

All very sobering!

Now the current article by Meha et al, reports that work over a project area of 293 ha could be completed in 24 hours opposed to 10 days with conventional technology. But this doesn’t allow for the very large number of GCPs – that don’t get created instantly! So that is just one of the issues that is ignored in Meha’s article. Overall Meha’s article is really reporting on an ideal scenario, no doubt to encourage further World Bank funding.

It seems that there are many laws surrounding the use of drones in Kosovo. Meha’s article provides no attention to these!

In many countries, with systematic registration significant work must be done to understand the complex legal, social and historic issues. That can only be done by boots on the ground and it takes time. With such histories land occupants want to see monumention as proof positive boundary determination and not just digits created by imagery. This article gives insufficient attention to these issues.

Drawing on Wallace’s pragmatic observations, he sagely concludes:

The UAV industry is what it is – there is no doubt that UAVs have many intriguing applications in many fields, although we have seen the existing service providers back-pedalling from things like pizza delivery or parcel delivery. At the current rate of development and with the concentration of resources being applied to the industry there is no doubt that further advances will be rapidly made.

But beware of the hype, and remember, in our industry it’s not about the platform, it’s about the sensor.

QED. Be wary of spin!

Thanks for the link to Wallace article Mr Alex. It is very useful.

If one pursues the fit-for-purpose line, there are indeed lots of potential applications for deploying UAV platform sensors. But clearly not all. I think this is where the Meha, Kelm …etc etc article only tells the story for one side.

More and more we are reading articles comparing UAV sensors with aerial and satellite imagery, but it is only for relatively small areas villages, communities, suburbs – or a road, or mine site etc., that you would consider deploying the UAV. But there is most definitely a marketing push for UAV sensors that simply fails to put this useful technology in its correct context for fit-for-purpose applications.

Meha, Kelm….etc etc article is interesting and informative, but just falls short of conveying a broader, objective perspective. In that regard, the article misleads in that it starts off discussing NSDI. No-one in their right mind would prepare the cadastre base data for NSDI – for an entire country or a province or even a large city – using UAV. It would not be cost effective and would take forever. Most definitely, good for capturing small areas or updating small coverages, but going beyond that requires alternatives. So for that I can only rate this incomplete article as 2 out of 5.

Fully agree Alex. I saw the note from Anthony Wallace some time back. Very sobering. It should boil down to what is fit-for-purpose. The UAV platform is sometimes suitable but not always.

It would be good to see more on comparative costs – satellite versus aircraft versus UAV (high and low altitude). Also a comparative analysis of environmental conditions such as cross wind, rain, cloud, smoke etc. And of course good examples of what situations are optimal for which platform.

The challenge in the UAV debate is that all too often presenters are comparing toys with sophisticated platforms and that should not be the case. So more often than not, we hear more of the spin- exactly as you forewarn.

Interesting blog – relevant considerations.

Leave your response!

MY NEWS

Department of Posts signs MoU with ESRI India Taiwan’s Integrated Disaster Management Ghana launches digital geospatial data system USGS unvelis national geologic map RICS launches global AI standard for surveying

More...Order both the copies for FREE!

PREVIEW THE BOOK

PREVIEW THE BOOK

________________________________________

The Drone Rules in India 2021

________________________________________

National Geospatial Policy of India 2022

________________________________________

Indian Satellite Navigation Policy – 2021 (Draft)

________________________________________

Guidelines for acquiring and producing Geospatial Data and Geospatial Data Services including Maps

________________________________________

Draft Space Based Remote Sensing Policy of India – 2020

________________________________________

National Unmanned Aircraft System (UAS) Traffic Management Policy – Draft

________________________________________

Advertisement

Interview

Kiyokazu Minami

Secretary General, Executive Director, Japan Institute of Navigation

Member, Leader of GPS/GNSS research group, Japan Institute of Navigation

Easy Subscribe

Previous Issues

- Vol. XXI, Issue 5, May 2025

- Vol. XXI, Issue 4, April 2025

- Vol. XXI, Issue 3, March 2025

- Vol. XXI, Issue 2, February 2025

- Vol. XXI, Issue 1, January 2025

- Vol. XX, Issue 12, December 2024

- Vol. XX, Issue 11, November 2024

- Vol. XX, Issue 10, October 2024

- Vol. XX, Issue 9, September 2024

- Vol. XX, Issue 8, August 2024

- Vol. XX, Issue 7, July 2024

- Vol. XX, Issue 6, June 2024

- Vol. XX, Issue 5, May 2024

- Vol. XX, Issue 4, April 2024

- Vol. XX, Issue 3, March 2024

View AllLog In

E-ZINE

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

View AllPartnership

10 - 12 February, 2025

The Queen Elizabeth II Centre, London

1-3 April

Porto, Portugal

9-10 April 2025

Singapore

23-24 April 2025

Washington DC, USA

5 - 6 May 2025

Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

12-14, May

Ottawa, Canada

21-23, May 2025

Wrocław, Poland

4 - 5 June

London, UK

8-12 September

Baltimore, USA

17-18 September

Hyderabad, India

21 - 24 September 2025

Baška, Krk Island, Croatia

29–30 October 2025

Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

3-5,November

Calgary, Canada

3-5 November 2025

Florianópolis, Santa Catarina, Brazil

28 – 30 April 2026

Vienna, Austria

21-23 May

Benidorm, Spain

View Past Events

Most Rated

Most Commented

Most Viewed